| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

Childhood

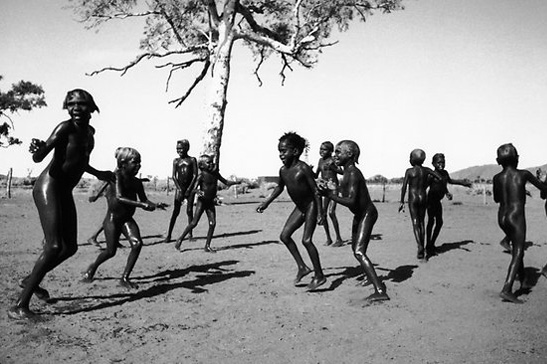

Without exception, the earliest Europeans to catch a glimpse of traditional Aboriginal camp life noted the boundless joy, exuberance and independence of the children. No other people seem to be as lenient or indulgent toward children as the Australian Aborigines, and many anthropologists have declared it to be the most child-centred society they have ever observed. As soon as a new-born infant returns to the camp with its mother, he or she becomes the unchallenged centre of attention. Older relatives and siblings as well as the parents continually shower the child with affection. From the beginning, a number of kin provide parental support. Although the child's actual parents have primary responsibility, the child's relationships spread throughout the entire clan or camp group. If the birth parents were to disappear, the child would experience no sharp loss. Usually, the child's name is given by the grandparents, who expend a great deal of time and energy caring for it. Children are never allowed to cry for any length of time; the parents and the entire clan see that their discomforts are quickly soothed or alleviated. Small children are breast-fed on demand, and they continue to suckle for three to five years. In spite of this, breast feeding is not a burden on the mother, since a number of female relatives often participate in a multiple nursing arrangement. In a baby's early months, many women nurse and care for it. Older women, especially the grandmothers, often have older infants suck a clear fluid that women can produce even after menopause. Aboriginal women say that their generosity in giving nourishment to their infants was learned from the Wallaby Dreaming. At birth the new-born wallaby, like other marsupials, crawls into the mother's pouch and remains there for many months, suckling at will. In contrast, placental mammals must drop from the womb to the ground in a permanent and abrupt separation from the mother; often they must compete and struggle for the mother's nipple. A marsupial mother licks the in-pouch infant's "bottom" when it defecates, and drinks its urine, thus keeping the pouch clean and redigesting the nutrients. The animal's complete, undisdaining intimacy and the love of the mother for the new-born serve as a Dreamtime archetype for Aboriginal motherhood. In spite of the flexible multiple parenting and nursing arrangements of the clan, the baby spends most of its time with its mother. When the child is very small it may lie in a curved wooden dish that the mother holds at her side or lays in the shade of some scrub while she carries out her hunting and gathering activities. Since children are involved in all collective activities, the mother's social activities are in no way diminished by her child. During a corroboree, it is not uncommon to see a child perched on its mother's shoulders, its tiny fingers clutching her hair, sleeping comfortably as the mother dances. Children usually wean themselves with no deliberate strategy on the part of the mother. As soon as they can walk, children are allowed to run free and participate in all the food-gathering activities of their parents. The mothers give tiny Aboriginal children digging sticks, and they quickly learn to feed themselves on the spot from what they can collect. Their education begins with the mother pointing out edible plants, animals, and insects. At a very early age Aboriginal boys become adept at throwing sticks and stones and can capture small lizards, mice, and small birds. This propensity is encouraged in boys but not in girls. In other respects, in the early years male and female children are treated equally, with the exception that the mother may be even more lenient with a male child. Aborigines openly and unaffectedly converse with everything in their surroundings—trees, tools, animals, rocks and such—as if all things have an intelligence deserving of respect. Not only the mother-to-be, but many members of the group may carry on a running conversation with the foetus as soon as it is established in the womb. The Aborigines believe that communication happens primarily on non-verbal levels, flowing as continually as life itself. The process of relatedness is not limited simply to linguistic exchange. A woman who served as nurse to the elderly Truganini (the last full-blooded Tasmanian Aboriginal woman, who died in 1897) relates that Truganini would carry on long, humorous, emotional exchanges with her oversized liver pill, trying to convince the pill to go down between her failed attempts to swallow it. From birth, nursing mothers talk to their infants about foods to be gathered and kin relationships with simplified versions of the words. They carefully tell a child what his or her relationship is to each of the people who come and go in their surroundings. The complex web of family relations that make up the kinship society allow the child to name its relationship to every person who enters its perception. There are no strangers, and the child has no sense of alienation from those around it. The kinship system encompasses not only the idea of family but also the idea of friendship. Everyone with whom one has even the slightest association is identified by a bond that is familial in quality. In Aboriginal encounters, anyone with whom a person is not connected through some widely extended kinship is considered "other" and is therefore avoided and treated with suspicion. There is no word for possession applied to a family relationship, such as "my uncle", "my husband", or "my grandmother". When referring to kin, Aborigines use an expression for which we have no counterpart; the literal translation is "self/uncle", "me/uncle", or "I/uncle". The term implies that a kin relative is an integral part of one's own being. Children learn to share the food they are given or that they have gathered themselves. Older relatives beg the children to share food with them or instruct them through games in the distribution regulations of their kin. For example, a male child may be told, 'This is your sister and you call her so-and-so (kin designation). When you get older you must give her some of the meat you catch, and she will give you some of the vegetables she collects. And if her husband treats her badly you must take her part'. The same child may be shown a female walking past and told, 'She is one of your mothers-in-law, you mustn't look at her face to face. You must not speak to her. But later, when she is married, you will send her gifts of meat and if she makes a daughter she may give her to you as your wife'. Such casual instructions go on repeatedly, every day of a child's life, building up a sense of relatedness and of knowing one's place in the ever-widening world. The kinship system is a network of relationships in which a number of people fill the same role. For example, besides the natural father, the brothers of the mother are considered father to the child. Before children can speak, they learn a sign language in which each relationship, be it sister, uncle, or brother-in-law, has its own hand gesture. Later in life, even across a crowd at a large gathering, an Aborigine can acknowledge a relationship to another person with a hand signal. This complex network of relationships is the essential fabric of Aboriginal life; it replaces all sorts of social and legal institutions. Aborigines view our mode of making friendships as part of an invisible kinship of which we are unaware. This web of relatedness, like their kinship system, is initiated at birth and is an inseparable aspect of the self. Because our social system has demolished the ancient kinship patterns and lines of ancestral relationship, we in the West must recognise our kin intuitively. However, genuine friends are, in effect, our kin. Aborigines believe that contact with those who are not kin is dangerous and can cause a loss of self. A child grows not by learning or preparing for life but by actually participating in the life of the community. To the Aborigine, the social and natural environments were created together in the Dreamtime and are based on the same plan; children become familiar with the two together. Along with information about kin and the environment, grandparents tell children simplified versions of the myths associated with their part of the country. These stories often take the form of songs, dances, and sign language. The child's training is a preparation for the series of religious initiations to follow. Aboriginal community is not based solely on psychological needs and material interdependencies; instead, a pre-existing structure of relatedness supports, fulfils, and extends the sense of self. Aborigines do not need to develop self-definition and self-esteem from the community because those qualities are given as a birthright to each tribal member. They do not have to escape the conventions and demands of community to pursue inner development and spiritual growth, because their entire social system is structured to provide and support those features. Freedom of Bodily Functions A crucial step in socialisation for children throughout the world is the process of learning to control excretory functions. In the traditional Aboriginal way of life, discipline is never used to accomplish this training. Older children contribute to the learning process by encouraging smaller children to defecate at a distance from camp. If encouragement fails, they might resort to light-hearted ridicule, but with great care not to offend the little one. In the next step, the child is encouraged to dig a small hole and cover the faeces. Although Aborigines are extremely uninhibited about body functions, defecation is always carried out in strict privacy because faeces can be used to great effect in sorcery. No restrictions apply to urination, however, and both children and adults urinate spontaneously in full view of others. The psychological traumas resulting from rigidly enforced toilet training in Western society do not exist among the Aborigines; they still possess the ability to live openly with each other and with nature. Aboriginal parents are for the most part extremely indulgent, going to great lengths to avoid denying their children anything they want. Adults endlessly pet and spoil children and tolerate a great deal of bad behaviour, disobedience, and even abuse. Aboriginal parents have had to develop methods for releasing their frustration with disobedient children. For example, a mother may threaten her child with a thrashing "in spirit". This may mean simply taking a branch and hitting his footprints, or pointing out a tree to the child, giving the tree the child's name, and then releasing a great display of rage on the tree without ever touching the child. It is considered a great personal defeat for an adult to lose patience and slap a child. If punishment is definitely called for, as in the case of one child threatening injury to another, it can only be carried out by the natural mother or father. If someone else, even close kin, tries to reprimand a child, an intense clan dispute is bound to ensue. Freeing the Emotions Aboriginal children are allowed to vent all their emotions in every form, from wailing lament to colossal tantrums. Screaming and writhing on the ground, hurling whatever it can lay its hands on at the offending adult, the child, if able to talk, also lacerates the alleged oppressor with foul language drawn from a large supply of obscenities that children master very early in their speaking career…. It amuses other members of society, including the victims of these attacks, to hear tiny children who barely know which is what shouting epithets such as: you crooked penis, you stinking vagina, you hairy arsehole, and so on, ad nauseam. The usual reaction of adults to child temper tantrums is to cover their face and other vital parts as best they can while the assault continues and laughingly protest until the child gets what it wants or forgets and goes away. Aborigines allow the expression of unlimited egoism in early childhood. Unfettered, self-centred, even tyrannical behaviour is considered appropriate for the infantile stage of life. To the Aborigines it is evident that babies are born with natural wilfulness and that they instinctively cry, scream, and otherwise focus their energy on having their needs met—usually by the mother's breast. As their mobility increases, children direct their activities solely on the basis of their own needs, desires, and ideas. Aboriginal childhood education rests on the conclusion that the sense of individual motivation is the universal characteristic of infancy and early childhood and that what needs to be cultivated is a sense of relatedness. As the child matures, he or she is increasingly introduced to obligations to kin and society and, later, to the spiritual mysteries of the Dreaming. As a result of this natural progression, adult Aborigines are extremely mild-mannered, easygoing, and relaxed and have none of the armoured defensiveness of the Western personality structure. Perhaps because of the freedom to release emotions given them as children, when the occasion arises adult Aborigines express their emotions with unrestrained intensity and then forget them. They do not harbour repressed feelings that can warp their relationships with their kin or with the metaphysical order. Thematically, Western education is the inverse of the Aboriginal method. While Aboriginal children are allowed complete expression of their emotions and desires, they are gradually and subtly encouraged to move away from the bondage of self-centredness toward an increasing sense of relatedness and a heightened sensitivity to collective and metaphysical realities. Throughout life, happiness is considered a process of enlarging identity through relatedness: to be is to relate. The child-rearing philosophy of the Australian Aborigines came face to face with its diametric opposite when Australia was brutally colonised by the nineteenth-century English working class. During the later Middle Ages, England had adopted patterns of cruelty, repression and subjugation of children (consistent with the subjugation of plants, animals and women that forms the basis of European civilisation). Nurturing was replaced by establishing complete control and mastery over children. All forms of affection were prohibited. Children were forced to conceal their own bodies from themselves and others. Parents and institutions exercised control through the use of corporal punishment. The birch became the predominant penalty and children were commonly whipped in public until they bled. By the eighteenth century flogging occurred on a daily basis in England, where it was viewed as a way of teaching adolescents and children self-control. The first immigrants to Australia were the products of the British penal system; the human instincts with which they might have appreciated or comprehended the beauty of the culture they saw were already beaten out of them. The Freedom of Childhood Sexuality The competitive spirit and the attitudes and drives associated with it have no place in the life of tribal Aborigines. None of their games and activities involve competition. Children's games mostly involve imitating adult roles, especially marital relationships and sexuality. Games such as "husbands and wives", "making camp", or "secret meetings" allow children to live out and enjoy the actuality of their future instead of dreaming up ambitious fantasies about "another life". When not running wild, shouting, and dancing, children play independently in loose clusters, where even the tiniest can be observed setting up little windbreaks, building mock campfires, pretending to cook, and often making rudimentary attempts at sexual intercourse. All games are structured around kinship relations, the names of which they have been learning since infancy. All children know who their potential husbands or wives or potential mothers-in-law or uncles are, and they address each other by these kinship names. Sometimes there are games of adultery in which a little boy runs off with the "wife" of another, dramatising the typical illicit relationship referred to by the Aborigines as "elopement". The erotic play amuses adults, but they also use it as an opportunity to instruct children about the correct sexual, marital and extramarital patterns allowed within the kinship system. The openness of the Aboriginal camp and lifestyle provides many opportunities for children to observe sexual acts among adults. Sexuality is considered a normal activity for all Aborigines; moral considerations only involve appropriate kin relationships. The sex act itself is never hidden from children (although adult couples tend to prefer privacy). Children sleep in the same camp as their parents, and sex is an open topic of conversation. An adult may playfully grab a child, calling him or her husband or wife, and pretend to make erotic movements and advances. As soon as infants are old enough to respond to the people who handle and talk to them, adults and older children may fondle and tickle their genitals, commenting on their size and shape and joking about sexual relationships. The only taboo about sex-related matters in some tribes is openly talking about semen or menstrual blood, which for the Aborigines are highly sacred. Very young boys soon muster the materials for making little toy shields, clubs, spears and boomerangs. Girls do not play with dolls; they are not raised to think of motherhood as their raison d'être. Rather, girls spend time drawing lines in the sand and learning about the symbols that represent the hearth group and other spiritual images. They use these to spin yarns about family life, the exploits of people they observe in the camp, or stories modelled on those given to them by the elders. These stories direct girls' attention toward human relationships, especially sexual relationships. Many adult women's rituals are love rituals, which also focus on influencing their personal relationships. From a very early age, children learn to read footprints, and by the time they reach adolescence they can recognise the individual footprints of as many as 200 to 300 clan members. Tracking is one of the primary learning processes of Aboriginal people. Mind and perception are trained to observe every physical detail of an imprint. The Aborigines believe that, in addition to the physical appearance, a footprint has vibrations from which an attuned observer can gain extremely accurate information. In remote parts of Australia police still rely on Aboriginal trackers who, it is said, can tell from a tire track in the sand the time of day it was made, the type of vehicle, the speed and the number of people in the car. Aboriginal children take great delight in sleuthing the tracks of couples who are in the midst of a heated secret love affair. After tracking them down, the children spy on every intimate detail and later mime the events in front of the entire clan, to the utter embarrassment of the victimised Romeo and Juliet. Aboriginal couples prefer privacy for their sexual life, but it is a rare commodity unless they can convince children to sleep elsewhere. However, as children grow older the observation of sexual intercourse develops into their most absorbing pastime. Aboriginal tribal people do not derive enjoyment or excitement from competition—it is antithetical to their sense of kinship and reciprocity with all. For example, when indigenous New Guinean boys who were sent to mission schools were trained to play football, they adapted the game so that play would continue until each side had exactly the same score. When Aboriginal boys were introduced to competitive football, the results were often bedlam and injury because, in their traditional society, aggression and confrontation were sanctioned only for the purpose of punishing those who transgressed Dreamtime Laws. Freedom Transforming From about eight to twelve years of age, the wonderful freedom and openness of male-female relationships among children begins to shift. During pre-puberty, the amount of time spent in erotic play begins to decline. Girls begin sleeping at the women's camp with their grandmothers or older female relatives, and the boys begin to separate themselves from the women's lives and activities. The boys are not yet old enough to join the men's camp, but by this age, they are already proficient in hunting small animals and lizards and often form their own camp group within the society, using their skills to obtain much of their own food. The male child begins his all-important separation from his biological mother as well as the maternal support of the entire society. The differences between the activities of boys and girls become increasingly distinct as their proclivities develop. The boys' camp is allowed to keep the rewards of its hunting escapades strictly for the boys' consumption, but girls of the same age contribute the food they gather to the pool consumed by the entire clan. Such patterns encourage girls and women to be aware and responsible for the whole group; males are urged to develop more autonomy. In this way, Aboriginal society cultivates the equally necessary qualities of autonomous action and group interdependence. In times of emergency, danger, or rapidly changing environmental circumstances, a balance of both these motivations is necessary for survival. The only absolute and consistent restriction placed on Aboriginal children is the prohibition against following adults when they depart to perform sacred initiatic rituals. Children are prevented from even going in the direction of sacred sites in the "men's country". In the child's mind, this rule stands out against his or her otherwise idyllic freedom and magnifies the mystery and importance of spiritual activities, especially the men's. Throughout childhood, the shadow of the coming initiation develops the awareness that life is marked by an irreversible advance over a series of thresholds, a progress toward increasingly secret and sacred dimensions of life. Over these thresholds all must pass, and by them each person is irrevocably transformed. |