| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

Gender Roles

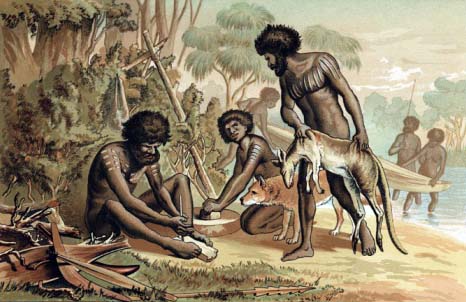

The division of labour between men and women in everyday life is implicit in many myths which clearly describe the food gathering activities of women while the men hunt larger animals. Many myths overlap in the areas they deal with. Thus, a myth about an ancestral hero may involve hunting lore, marriage customs, the role of men and women and their responsibilities to their kin, as well as taboos surrounding food. The actions of the Ancestral Being himself therefore sets the eternal pattern for Aboriginal society. Men had the aggressive role, the responsibility of spearing and capturing animals, or of fishing and of providing the meat for the family. Women were expected to gather vegetable foods and fruits, grind seeds, cook damper and dig for roots. Of course if small, edible animals came past, they were not forbidden to capture them, though it was often the young children accompanying their mothers who pursued small lizards and marsupials. Women did not, however, hunt large animals. The following stories told to Kabbarli early this century by a small group of Aboriginal people at Ooldea, a camp at the edge of the Nullarbor Plain, tells of what befell certain women who hunted meat in the Dreaming times. The Women Who Hunted Meat In Yamminga times, there was once a tribe ofjandu (women) who used to live by themselves at a place called Yardagurra, in the Great Australian Bight. Now, it is the law of the tribe that men and women should live together, not separately, and that the men should hunt for wallee (meat) each day, while the women go out to gather mai (vegetable food). But these jandu did not observe the law: not only did they live by themselves, but they went out meat-hunting each day, armed with men's weapons: spears, spear-throwers, and hunting knives. Like men, they stalked and speared the kangaroo, and hunted the emu across the plain. Tchooroo the Great Snake, whose task it was to uphold the law, reproached these women for their way of life. 'You should not hunt for wallee,' he told them. 'That is men's work. You should collect mai. That is women's work and this is the hunting law.' But the women did not take any notice of Tchooroo's words; they went on hunting for meat just as they had done before. When Tchooroo saw that they had not listened to his words, he became angry and turned all the jandu into jiddi joonoo (termites' nests). All the tall peaked jiddi joonoo which stand now at Yardagurra were once the meat-hunting jandu of Yamminga times, who were punished by Tchooroo the Great Snake because they broke the law of the tribe. Women were expected to provide as much variety as they could in the foods they gathered and to diligently search for vegetables—if necessary, far from the camp. Generosity was admired and selfishness deplored. Joord-Joord (Shag) the Lazy Woman In the long-ago Yamminga times, Joord-Joord was a jandu (woman) and she had two sons. Every day her sons went into the bush to hunt possum and other meat, and when they brought home their game, they always gave their mother as much as she could eat. Joord-Joord should also have gone out each day to collect roots and berries and other vegetable food, and to look for bardi and small game such as lizards, for that was a woman's work. But she was fat and lazy, and every day, every day, she gave her two sons nothing but nyell-guru and ngar-ran (white ants and ants' eggs), which she could collect just outside their camp. She would go a short distance and fill her bin-jin (bark vessel) with these because they were so easy to get. When her sons came home with the langoor or wallaby or goanna they had hunted, every day they saw only the same food in their mother's bin-jin: nyell-guru and ngar-ran. That was all their mother could be bothered to find for them. At last, they grew tired of eating ants and ants' eggs, and one day they threw all the contents of their mother's bin-jin on the fire. As they burned, the ants and the ants' eggs made a loud, crackling noise. 'What do I hear burning? What is it?' Joord-Joord called out. 'Nothing,' her sons told her. 'It is nothing.' And now, every time they came home and found nothing but ants and ants' eggs in Joord-Joord's bin-jin, they burned them. One day they came home early, bringing fat langoor with them. They found their mother sifting and sifting the nyell-guru and ngar-ran. The eldest son said to his brother, 'Let us punish our mother, because she does not follow the Law of the tribe and bring us proper food. She gives us nothing but that no-good nyell-guru and ngar-ran, while we bring home good meat and always give her a fair share of it.' When Joord-Joord looked up and saw her sons coming towards her, she guessed what was in their minds. 'They are going to punish me because I do not go out to collect proper food for them,' she thought. She seized her digging stick and began to hit her sons with it as soon as they drew near. Then each of her sons picked up fire sticks from the fire and hit their mother on the back. And that is why, when Joord-Joord the shag became a bird, she had a black back. 'Joord-joord! Joord-joord!' she cries as she goes along. Women should bring home proper vegetable food when their sons fetch good meat for them: that is the law of the tribe. The following stories, the first from the Central Desert and the second from Warburton/Kimberleys in Western Australia, are most revealing about the duties of wives to provide food for their husbands, the need to prepare it carefully and the potential for jealousy between wives should the husband favour one more than the other. The Wanambis Punish Their Wives During the early days of Creation, two snake-brothers camped with their two wives at the mouth of the Piltadi Gorge at the eastern end of the Mann Ranges. Every morning the two wives of the snake-men walked to a spring nearby to gather food and especially to catch small marsupials, called mitika, by smoking them from their burrows. They would gather spinifex grass into bunches, push it tightly into the mouth of a burrow, and set this on fire. When the blaze was strong enough, they inverted their wooden dishes and, cupping them over the hole and fire, beat them up and down to cause plenty of smoke. The animals inside would come to the entrance of their burrows to escape, and would be suffocated in the fumes. Every night the two wives brought the animals back and threw them in a heap for the men to cook. The men were so well fed that after a while they did not bother to hunt anymore and just sat around singing and making ceremonies. Their laziness enraged their wives and one day they rebelled and cooked and ate all the mitikas themselves, providing nothing for their husbands. The husbands were furious at the action of their wives; they travelled away from their camp underground some far distance and made another camp where they would not be affected by the smoke from the women's fires. They decided to change into wanambis and to punish the women while in this form. Each day while the women were hunting, their husbands who were in the form of wanambi snakes would make tracks and burrows across their path, enticing them after large game. But each day the women were able to catch only a small carpet snake, which barely fed them. The women pursued the wanambis until finally the wanambis revealed themselves as giant serpents with manes and beards and devoured their wives. This story serves as a moral tale concerning the duties of wives to feed their husbands and also implies that wives should not resent the time men take with ceremonial matters. Stanley West, Warburton The history of relations between men and women is fascinating but not always cordial. As many of the Creation stories have shown, women originally kept the sacred Law, they sometimes owned the sacred objects and kept them in their dilly bags, but at some point in the history of the Dreaming, their status was altered; the men stole the sacred Law and have retained the knowledge ever since. As in many societies of the world the women became the subject of jests by the men due to their garrulous nature—they were far too frivolous to be entrusted with the sacred matters of Law; they gossiped too much. The Fights Caused by Bulangarr the Rat-Woman Now I'm going to tell you about our custom of fighting in groups and who said we must always settle our disputes like this. This was in another time. Who created this Law? Rat-woman. She was a terrible trouble maker. She went about telling stories to all the people about other people, and everyone used to fight because of her lies. You can see what she is like from her tracks. First she makes one big hole, then she makes a lot of small ones leading from that big one. That tells you she has many conflicting ideas—she likes putting other people into trouble, and of course she gets into trouble herself. As a result of all her mischief all the people had a ganygarr in the Wongar times, an all-in fight. The fought with many spears and when their spears broke up they turned into the leeches you can see today. Djawa, Milingimbi The gossiping rats are the subject of songs from both the Wonguri-Mandjikai cycle of the Moon-Bone and the Rose River love song cycle. In most accounts of the history in the shift in relationships and roles, the women, however, remained unperturbed. The roles which became fixed in the Dreaming era, of men hunting and keeping the sacred Law and ceremonies and of women gathering food, grinding seeds and bearing children continued over the millennia to come, for the women had the most sacred gift of all. As the Djankawu Sisters said when their dilly bags containing their sacred rangga were stolen.

|