| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

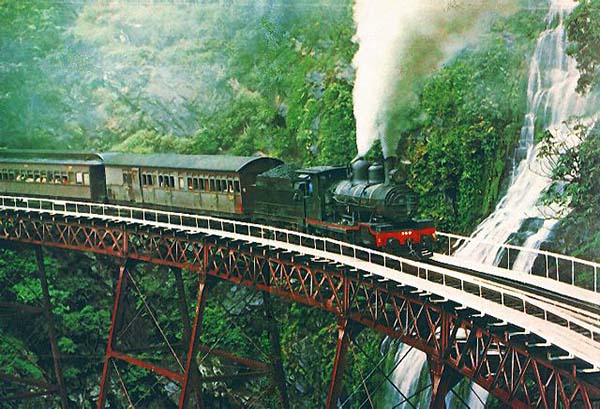

How men toiled and died

In 1891 when John Robb and his brave band of railroad builders completed hand-carving the mountain line from Cairns to Kuranda, it carried supplies to miners scouring north Queensland's rainforest-covered ranges for gold. Construction of the line began in 1886, 10 years after Cairns had been established as a port for the Hodgkinson goldfields. The new settlement had foundered after being upstaged by nearby Port Douglas, which offered an easier route for the packhorses and bullock wagons that humped supplies up the mountain. "Cairns as yet scarcely merits description," declared The Picturesque Atlas of Australia in 1888. "It's never likely to come to anything," sneered the Cooktown Herald. Robb and his workers changed all that when they completed the 34km of mountain railway, which provided a year-round supply link. The most difficult line ever constructed in Australia, its 98 snaking turns, 42 bridges and 15 tunnels took five back-breaking years and cost the lives of 29 men. Since Robb's railway brought it back to life, Cairns has prospered. It has been a centre of gold-mining, logging, pearling, fishing and the sugar-cane industry. Its harbour, now the home of one of the world's greatest game-fishing fleets, once sheltered sailing ships loading Cape York cedar bound for Europe, and was the South Seas base for whaling boats from Boston and Connecticut. Robb and his men would not recognise today's Cairns. When they arrived it was a mosquito-infested sprawl of shacks and tents fringing the mangrove swamps of Trinity Bay. Flickering kerosene lamps lined muddy streets lined with sly grog shops. Opium dens were wide open—patronised by Chinese workers off the goldfields. Rip-roaring residents spent most of their time boozing and brawling at the shanty bars run by the town's two women hoteliers—Limerick Nell and Mother Brandy. To excuse his drinking habit one early settler wrote: "The only water available was salty. We used to get the most horrible pains in our innards—we found gin to be the best cure". The building of the railway started with a party on May 10, 1886. Premier Samuel Griffith turned the first sod, a bullock was roasted in the middle of town, and Robb's men were given all the free beer they could drink. Most of them were Irish and Italian. Called navvies, they were paid only 85 cents a day and welcomed the opportunity to drink themselves silly. At night the town's little lock-up was packed with drunken navvies and the overflow was confined on a barge in Trinity Inlet. The next morning 600 sore-headed men began hacking through jungle. Over the next five years the work force increased to 1500. To get a job, labourers had to provide their own shovel. As their equipment was limited to whatever pack mules could carry up the mountainside, earth moving was done by wheelbarrows and buckets. Cement was shipped in casks from England, carted up the mountain and mixed by hand as it was poured. Iron work was hand-forged on the job. Using picks and sticks of dynamite, Robb's workers carved huge embankments and tunnelled through 15 rocky ridges. Many of the line's 29 victims fell to their death during the construction of the bridges that span the gullies and gorges. Others were killed in dynamiting accidents. The worst disaster occurred when seven men were crushed by a cave-in during the excavation of the 15th tunnel. The torrential rain of the monsoons caused horrific landslides. In one week 1.8m of rain cascaded on the workers. They also endured the steam-bath heat of summer, deadly snakes and attacks by hostile Aborigines. As they clawed their way up the range, the men established work camps which grew into small communities where the workers' families lived in tents and shacks. The camp dwellers became part of the terrible human toll. Scores died from swamp fever, scrub typhus and snake bites. Describing her childhood in the camp near Tunnel No 10, one worker's daughter recalled years later: "We had a bark house with big sheets of bark for the roof and sides. Mother lined them with cretonne. It had an earth floor, but they stretched canvas over it and pegged it down tight. Of course it was dusty so Mother scattered (wet) tea leaves on the floor to pick up the dust, then swept it all out." Her recollections of an accident involving her sister illustrated the tyranny of isolation the families faced. When the child's knee was shattered by a flying stone from nearby blasting at the entrance to Tunnel No 10, it took six days to get her down the mountain to the Cairns hospital. The reason for much effort and sacrifice was the gold, tin and copper that had been discovered in the mountains inland from Cairns as well as the agricultural and grazing potential on the temperate Atherton Tablelands. For the area to prosper it was imperative that a railway was built to replace the tortuous mountain tracks which were impassable in the wet. The situation had come to a head in 1882 when a severe wet season prevented supplies getting through. With thousands working the Herberton tin fields facing starvation, the government decided to build a railway. After a long argument about where it should start Cairns was eventually chosen over Port Douglas and Innisfail. Bushman Christie Palmerston, the region's greatest explorer, was commissioned to survey the route. Once Robb's men completed the horror stretch the Kuranda, the railway was expanded hundreds of kilometres out across the tablelands and Cairns boomed. In the 1920s, as mining declined, Cairns became a thriving sugar centre. Still a frontier town, it attracted famous writers like Somerset Maugham, combing the South Pacific for stories; cowboy novelist Zane Grey; and Joseph Conrad, who skippered the Australian sailing ship Otago before becoming the renowned writer of sea adventures. In the 1930s, before he became a Hollywood star, Errol Flynn sailed his yacht Sirocco in to Cairns in search of adventure. During World War II the railway carried thousands of American and Australian service men and women to bases on the tablelands. Cairns was an RAAF Catalina flying boat base and the major repair depot for the US 7th Fleet. Four US heavy bomber squadrons were based along the line at Mareeba. With the growth of tourism in the 1970s, the small motor rail which ran the service for years was replaced by a diesel locomotive pulling a string of vintage coaches. Queensland Rail restored them to their original splendour—varnished timber, plush seating and lace iron-encased mounting platforms. In 1973 the mountain line was the scene of Australia's Great Train Robbery when two masked bandits hijacked a railway payroll. Blocking the line with a rock, the robbers held up the crew and fired several shots into the luggage compartment. Before disappearing with the $7000 payroll, the pair immobilised the train by chaining its wheels to the rails. The tourist line ends at Kuranda station. On one platform stands a pick and shovel memorial to Robb and his men. A little way back down the track is Robb's Monument—a 22m high rock monolith. It marks a nightmare section of the line where diggers literally roped themselves together to cut the track-bed along the near-perpendicular mountainside. Robb held his men in high esteem. He paid for a lavish party at which the workers celebrated the opening of the line. He might not have been so generous had he known that the Queensland Government would challenge his construction bill of $520,000. The dispute went to arbitration and Robb was eventually paid only $40,000. |