Big Red Tour © Jens Hültman

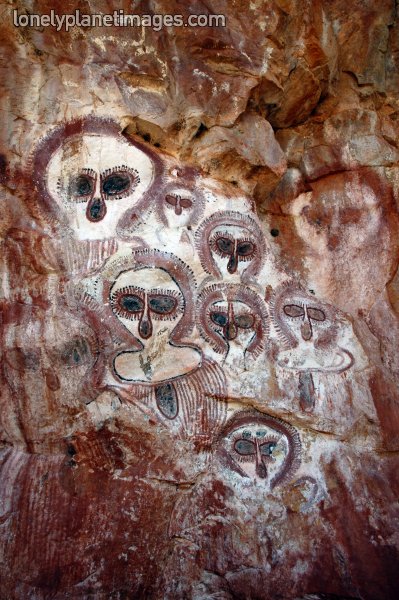

I picked up Jeff, a hitchhiker on the road to Derby. Jeff lived in Darwin. He made a living as a chess piece maker. We talked about the rock paintings that northern Australia is full of. The Aboriginal Wandjina paintings with white, ghostly faces without mouths are typical of the Kimberley. In the Kimberley, you also find another type of painting, the so-called Bradshaw figures. They look lean and African. They are named after Joseph Bradshaw, an explorer who led an expedition into the Kimberley in search of good pastoral land in April 1891. The Aborigines think that the paintings are crap. According to the Aborigines, some people who were there before them made the paintings. For someone who as a young man had read Von Däniken, this proved to be a source of fantasy. It has generally been believed among academics that a big wave of migration took place around thirty-five to forty thousand years ago. According to Jeff, the Bradshaw paintings proved that the academics were wrong—academics and other authorities always are in Australia. Jeff's Von Däniken-inspired theories are a part of the Australian folklore that tells tales about the Aborigines not being the first ones on the continent. According to the folklore, the Aborigines exterminated the first inhabitants. Therefore, logic concludes, the European Australians should not suffer from a guilty conscience for the plight of the Aborigines during the last two hundred years since the European invasion. 'The Abos were just as bad themselves, weren't they?' Forty thousand years ago... The Aussies are innocent. 'It was the friggin' Poms that invaded Australia waren't it?' This is not the only myth. An interesting fable claims that Egyptians visited New South Wales and left hieroglyphics in a cave. A South Australian story talks about visiting Polynesians. In addition, there was a supposed Dutch colony in the inland of Queensland in the 1600s. A Portuguese mahogany ship sunk on the south coast. It's as if Australia is not magical enough already. We drove into Derby, a former meat-exporting town. Cattle used to be driven down the Gibb River Road to be slaughtered and transported overseas, ending up as hamburgers in the United States. Now they are fetched with road trains and transported down south before they meet their destiny. Derby is a sleepy little town nowadays. The rationalisation of the cattle industry has brought a big change to the Kimberley. We passed the shotgun club. Other towns have a rifle or a gun club. Derby has a shotgun club. I dropped Jeff off on the outskirts and checked in at the caravan park. A few sites down, under the shady trees, stood a white Morris Minor. An old man in his late sixties with an Old Testament beard seemed to be travelling in it. He camped in a very small tent. He was stripped to the waist, revealing a skinny body. He was talking to a young couple. He had an interesting look. I walked over, introduced myself to the young couple, who turned out to be Dutch, and to Charlie. He was very much Irish. 'I'll be over and talk to you later, son', he told me. I put up the cot, as always with some difficulty. Irish Charlie got over to me and exclaimed: 'The other day I was talking to this young Australian who had been to Ireland. He came back with a great admiration for Jerry Adams. See, Jerry Adams is a hero. He comes from a long line of fine Fenian officers who have been fighting the bloody Poms.' How do you reply to that? Apparently, you should not reply by telling Charlie that the IRA are a bunch of bloodthirsty terrorists. Charlie had met a middle-aged Dutch man who had called the IRA bloodthirsty terrorists. He thundered like an Old Testament prophet: 'The Dutch cried like babies when the Nazis occupied them. Four years of occupation and they cried like babies for help. Then we had to come over and liberate them from Hitler. And yet, this Dutch moron denies us, the freedom-loving Irish, the right to fight our British oppressors. We have been occupied for four hundred years', he thundered on.' And do we cry like babies?' he added rhetorically. The answer was apparently supposed to be No. I asked him what he meant by the Irish having liberated Europe. Ireland was not in the Second World War but an army of volunteers had been set up in Ireland, Charlie told me. As a young man, Charlie had fought in this volunteer army as a mechanic. His family had been paupers. He had not learned to write until he was twenty. He was divorced and had a son living in Australia. Now he travelled around the Australian countryside to figure out why the countryside was deserted. He interviewed people and studied local newspapers. He had come up with his own theory. The big capitalists of the world like Murdoch and others were draining the countryside because they wanted control of the land when a future Armageddon of war and disease would decimate the population. At that point they could return to the land and live off it, while the rest of the Earth's population would perish in the cities. He told me that he travelled with very little money. He was stuck in Derby because his Morris Minor had broken down, the gearbox had given up on him. I tried to imagine his small car next to one of the huge road trains out there—but he need not fear being run over by them, since his little vehicle would pass under a truck without a problem. He lived on bread, fruit and coffee. Once a week he bought himself fish and chips from a take-away store. Once a month he had meat. I looked at him. I could count the ribs on his thin, old body. His big theory had to do with the cruelty of the Anglo Saxon race. This race was the most murderous and bloodthirsty of all throughout the history of humanity, according to Charlie. He told me how the Brits had put Irish prisoners on boats in the Harbour of Belfast and set them on fire during German raids so that the Germans would bomb them and kill the IRA's "freedom fighters". 'See, son', he told me, 'we, the brave Irish people, are just doing what the Allied did to the Nazis during the war. They went to Germany and hit them where it hurt the most. They bombed them in Hamburg. They bombed them in Frankfurt. They bombed them in Berlin. We do the same. We go to Britain and bomb the British tyrant where it hurts him the most. We bomb them in Liverpool. We bomb them in Manchester. We bomb them in London. We strike the enemy right in his evil heart.' He felt uncomfortable in the Kimberley. There were too many big and powerful Anglo Saxon cattle lords for his taste. He had lived among Canadian Indians and worked for their land rights against the big mining companies. He saw many parallels to the Aborigines. After two hours of thunderous preaching he left and returned to his quarters, perhaps with the impression that he had found a disciple. I had dinner at a local Chinese restaurant. It doesn't take you long to get tired of the overcooked Anglo slop—and steaks burnt to leather—served at the pubs in the outback. When there is a Chinese restaurant in town, go for it. This one is situated next to an Aboriginal hostel and a church. The congregation was singing beautifully in the dark, humid night. Their voices sounded Polynesian to me. I walked over to the "Spini", the Spinifex hotel. The guys in the bar looked rougher than rough. Their tattoos had the crappy look of prison. The place vibrated with suppressed violence. One of the photos on the wall featured an amateur photo of female genitals, presumably taken during a boozy night at the hotel. 'Show us yer pink parts. Aw fuck, burp, show us yer pink parts! What d'ya reckan, ay? Be fair dinkum, ay?' It's a rough life being a female in the bush. A mating call of: 'G'Day pig face! Fancy a shag, ay?' is considered socially acceptable. 'What's the matter with ya? Can't ya take a joke, sheila?' The rough guys in the bar left for the beer garden. The place had a very bad vibe. I finished my first and last beer at the Spini, as fast as I could. As I left, I caught a whiff of marijuana. I walked faster. It was not my scene. |