| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

American Patriots:

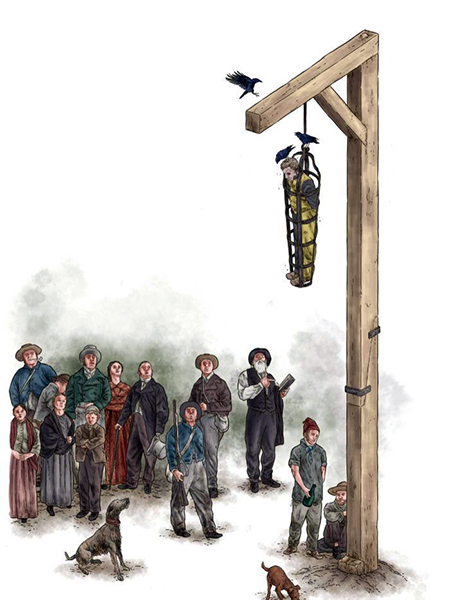

In 1837 in an ill-starred attempt to spread the message of Independence, a Patriot army launched an invasion of Canada, hoping to provoke a general uprising. It failed to light the fires of rebellion and the British captured 92 mostly American citizens, members of the American Patriot Army fighting with Canadian republicans for independence from Britain. Military courts smartly and highly illegally banished them in 1839 to Britain's remote and wild new island colony of Van Diemen's Land, now the State of Tasmania. The American freedom fighters were mostly civilian recruits and family men—farmers, carpenters, clerks, ploughmen, merchants. They were virtual slaves at penal posts on the island for up to 10 years, and 14 Patriots died as convicts. Some escaped on American whalers. When finally pardoned, the Americans were let loose to find their own way home. A few never did. They married free settler and convict women and remained in Australia. But most of the Patriots returned to their families in North America and have many thousands of descendants in the United States and Canada today. The Patriot convicts sent to Tasmania were the first Americans imprisoned overseas and the first political prisoners. A small monument unveiled by the Canadian High Commissioner 1995 in Princes Park, Battery Point, Hobart, which honours "The memory of 92 exiles transported from Canada" fails to mention that the vast majority were American patriots. The Patriots' War was mainly a Canadian issue, but the United States, especially Niagara County, was heavily involved in the brief and abortive conflict. The only person hanged as a result of the rebellion was a US citizen. However, US ship, the Caroline, was burned and sent over Niagara Falls. Perhaps the prime instigator in the rebellion was William Lyon Mackenzie, a Scottish immigrant who started a newspaper in Ontario. His editorial stance soon evolved into strong criticism of government practices. He moved to York (now Toronto) in 1824 and eventually led a rebellion to take Canada back from British control in 1837. Failing there, he went to Buffalo to recruit an army. He issued a proclamation promising recruits 300 acres "of the most valuable land in Canada" and "$100 in silver payable on or before the 1st of May next." A sizable army was raised, which took over Canada's Navy Island, then occupied by only one family. The Caroline, a US ship ferrying arms and ammunition from the US to Navy Island, was attacked by Commander Andrew Drew of the Canadian Army, who led seven boats with 45 men on the commando raid. The Caroline was set afire and sent over the falls, which caused an uproar in the United States and nearly precipitated an all-out war. The rebellion, however, was very short-lived. Court trials of Patriots began: Canadians were charged with treason and Americans with waging an illegal war. Only American James Morreau went to the gallows. The Niagara Chronicle, a Canadian paper, reported Morreau moved his lips in silent prayer as the trap was sprung and he "paid his debt to nature and mankind without a struggle". The Chronicle also wrote about the large crowd that witnessed the hanging and commented on the many women there. "We allude to the number of respectably dressed females who seemed collected there for the purpose of beholding some pleasurable sight." The paper noted, "In the Old Country no females attend such spectacles except those of totally depraved and wanton habits." Samuel Chandler and Benjamin Wait, both Canadians and therefore British subjects, were indicted for high treason. The jury returned a guilty verdict with a recommendation for mercy. The lieutenant governor, George Arthur, and later governor of Tasmania, imposed the death sentence and only reluctantly amended the sentence when Wait's wife, Maria, and Chandler's daughter sought clemency from the Earl of Durham. The lieutenant governor reluctantly acquiesced: both men would be spared and given life in "one of Her Majesty's penal colonies". These two and all the others were taken first to London, with a journey across the Atlantic that took place "in abject misery". They were then shipped to the penal colony at Van Diemen's Land on a journey that took four months. It was an unpleasant trip. Wait wrote, "Surely, if there are places in human abodes deserving the title of Hell, one is a transport ship crowded with felons culled from England's most abandoned criminals." They arrived at Van Diemen's Land on July 18, 1839. Whilst the English penal colony was no picnic, nevertheless the prisoners fared better than on the transport ships or in the temporary jails that housed them during the long journey. And it was far better than the French penal colony of Devil's Island. Upon landing, the prisoners were marched to the Hobart Penitentiary, where the governor, Sir John Franklin, explained the terms of their imprisonment. Actually, the terms seem quite lenient when compared with the wretched conditions in jails and prison transport ships. The prisoners were given a probationary period when they were allowed to leave prison during the day, assigned to "masters" on the island where they would work for free. After a satisfactory probation period, prisoners were issued a "ticket," and were able to seek their own masters and work for slight pay. Eventually, Samuel Chandler and Benjamin Wait were assigned to a 2,000ha estate about 90km north of the Hobart Prison. Chandler worked as a carpenter and Wait as a clerk and storekeeper. The work day, Wait wrote in his journal, began at 4am and lasted until 11pm. When they were off work, the ticket allowed them to roam the island. This presented the opportunity for escape, when the men learned several American ships were at the Hobart harbour. In December 1841, Chandler obtained a 10-day pass and went to the harbour, where he was befriended by a fellow Mason and captain of one of the American whaling ships. The men made their escape plans. They could not board the ship in the harbour because it was thoroughly searched before it left. The work day, Wait wrote in his journal, began at 4am and lasted until 11pm. They obtained a rowboat under pretext of going fishing and rowed laboriously out well past the harbour. They were in the boat, with little food and water, for several days and about to return when they spotted a whaler and were taken aboard. The men were on the first leg of the road to freedom, but still thousands of miles and seven months away from home. Unfortunately, the whaler hit a violent storm off the coast of South America and was wrecked near Brazil. Wait and Chandler soon found themselves penniless, but glad to be alive, in Rio de Janeiro. Another American captain agreed to take them to New York, where Freemasons took care of train tickets and the pair travelled to Niagara Falls. Here Maria Wait was working as a teacher. About the reunion with his wife, Wait wrote, "Over the circumstances of our meeting I will draw the curtain of silence and leave the fancy of the reader to portray it." |