|

Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

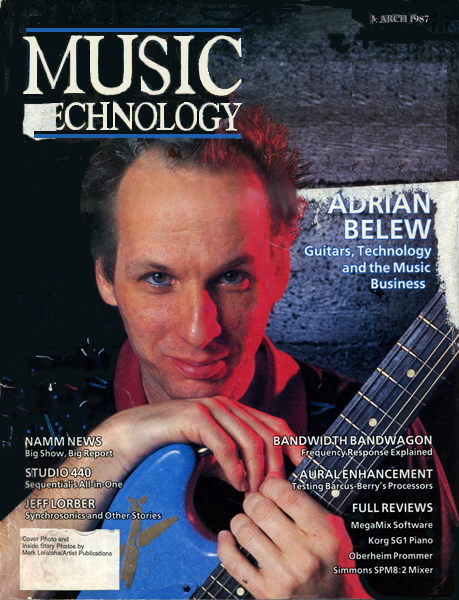

Adrian Belew interview by Joy Williams

Adrian Belew is perhaps best known for his part in the 1981 reformation of King Crimson—one of the most progressive (and élitist) bands to emerge during the seventies and led, in the main, by Robert Fripp. As a member of the group Belew played a major part in making the Discipline album, released in 1981, the album which many hold as the most revolutionary example of the group's work. His playing with Talking Heads on Remain in Light (1980) and The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads (1982) also left a strong impression of his attention to textural detail, although the range of artists he has worked with is extensive in style—and success. Belew had his "big break" when he was invited to play with Frank Zappa and The Mothers, later touring with the band. He has also been featured on two albums with David Bowie—Stage (1978) and Lodger (1979)—as well as working with Jerry Harrison, Garland Jeffreys, Robert Palmer and the Tom Tom Club. His solo career has developed over the years, breaking new ground and expanding into new areas of interest, including production. The direction of his latest solo album, Desire Caught by the Tail, is of experimentation with rhythm and instrumentation. The parts are mostly played on guitar but, as usual, Belew has gone out of his way to get a great variety of different sound textures from the one basic instrument—and the experiments don't end there, either.

But the road to becoming a guitar hero is long and tortuous. Adrian Belew's began around the age of four or five when, in defiance of his family's non-musical tradition ("I don't think there's anyone musical in our whole family but me"), he began to sing. This was something of a shock to his hard-working, salt-of-the-earth Midwestern parents. But they weren't put off by it. Not at all. In fact, they were quite proud of him. Baby Adrian was brought out to perform at family functions, or accompanied by the jebox in bars in the series of small towns (mainly around Cincinnati, Ohio and across the border in Kentucky) in which the family lived. "Then when I was about 10 years old I really got the bug to play drums," he recalls. Of course, he talked his parents into buying him a kit, he practised, and he joined the marching band at school. And he went to concerts—Stravinsky and Ravel and good, unusual modern music. "I think those were really the first things that moved me—Gershwin and things like that—even before I became pop-conscious I didn't really think much about pop music until The Beatles came out when I was 14. "The very first time I saw them, I went upstairs and cut my hair in a Beatles haircut. I became very fanatical about it, and about a year or two after that I got in my first band, which was strictly a Beatles copy band. We wore little Beatles outfits and my dad eventually bought me a Beatles drum set. And we were a good little band. We were called The Denims—we wore denim outfits sometimes and we did credible English versions. "Still, I wasn't a guitarist. It was only about the second or third year into The Denims, I think I was maybe 16 or 17, when I decided to start writing. I was very happy being a singing drummer but I wanted to write songs, and obviously I needed to take up the guitar. So I started teaching myself. I contracted mononucleosis and was banned from school for eight weeks, so in eight weeks I taught myself to play the guitar and started writing songs and everything. Of course, I did it all wrong, so when I showed the song to anyone else they'd say, 'What on Earth? What's that chord?' I just put the notes together the way I heard them. And then gradually I got a lot better at guitar playing, particularly because about the same time or shortly thereafter the big surge of Jimi Hendrix and Jeff Beck and all those people started to emerge. That really kind of fuelled me to become a guitar player." Adrian continued to master styles of the guitar greats of the Sixties until reaching his mid-twenties, when he felt he'd pretty much figured out everything his heroes had done. Of course, he then felt: "Well, this is nowhere, you can go on sounding like these other guys forever," so he stopped and went back to the drums. As many musicians have found to their cost, however, the guitar is not such an easy habit to kick. And eventually Adrian succumbed, bought the Stratocaster he'd always wanted, and started all over again...

"I'd stop myself every time I'd hear myself play a familiar lick. This is how I pared myself down to nothing but my own little ideas. I broke all my habits of playing like anyone else, and what I was left with was the beginning of finding my own musical voice. I was really thinking about trying to get the sounds that were in my head onto record. My theory is that if you have something of your own even remotely special, and you continue to refine it and do it over and over and perform that way, eventually someone will see and you'll get your shot. I've always thought that to be true. Now, if you're ready for it, it'll be to your advantage; and if you're not, you may never get another shot at it. "The first big break for me was when Frank Zappa walked in to hear a local bar band I was in—we did regular old songs, you know, Paul McCartney songs and David Bowie songs and current hits on the charts—this was 1976. He walked in and recognized something special in what I was doing and said, 'I'd like you to audition for my band.'" Joining Zappa as a sideman left Belew with two sets of feelings. "One was that I still wanted to get to the point of doing my own music and take control of it; that was a minor feeling. The overriding feeling was: 'Gee, this is great. I can't believe I'm standing here on stage with Frank Zappa, or he's showing me this, or I'm learning that, or I'm traveling around the world, or I'm making x amount of dollars, or I'm meeting all these people.' It was all very, very exciting, and continued to be exciting all the way through the next six or seven years. And then I started getting tired of touring. But at first it was pretty amazing, and it's so continual that you don't really get a chance to reflect on it very much. The first thing I did was a year's worth of work with Frank Zappa—very intensive, because he is a well-known hard worker." Brian Eno caught the Zappa show in Cologne and, recognizing something special, tipped off David Bowie, whom he knew was looking for a guitarist. A couple of nights later Bowie was at the Berlin show and invited Belew to join him that same night. "Each thing has its own clique," Belew maintains, in explanation of what might seem extraordinary luck. "Obviously, I've gotten into the clique of Laurie Andersons and Talking Heads and Robert Fripps and... I don't know how I got involved with Laurie Anderson. I saw her performance twice and was pretty overwhelmed by it and didn't say anything to her, didn't introduce myself, and really didn't think we'd ever work together or anything. Then one day I just got a call from her. She had gone on record as saying she would never work with a guitarist. Well, she didn't consider me a guitarist, she considered me a person who makes sounds. And that is attractive to her, of course. When we did our recordings together she would always say, 'Now, make this kind of sound.' I would just give her endless options of different sounds." Belew is no speed-guitarist—he'd lose a fingering contest with Yngwie Malmsteen or Eddie Van Halen—but the mechanics of guitar playing are not what make this musician special. "My education was really based on figuring out as exactly as possible what other people were doing on records. I'd listen for hours and pick out the exact parts, and of course you have to try and pick out the sounds, too. So I started collecting fuzztones and eventually wah-wah pedals and flangers and anything that would make a sound. My fascination has always been pretty much with the sounds, and early on I decided that what I wanted to do most was to make the guitar sound like other things. My way was to make it sound like anything I could imagine, and things I couldn't imagine, as well.

"Technology lends itself to that a lot. Nowadays, when you have digital guitar synthesizers and such, you can get even more exacting with it. You can decide you want your guitar to sound close to a violin, and pretty much approximate it because it is not an extremely difficult thing to break down the components of what a violin sound is. Some sounds are pretty difficult to analyze, but you get pretty good at it if you work on it a lot." The first time I saw Adrian Belew live was with King Crimson in Berkeley, California. When I remind him that this was the night that Robert Fripp was ecstatic because "nothing went wrong," he laughs. "Well, it's funny... I just went out yesterday and bought the new King Crimson release, which is called The Compact King Crimson, and has one album of the current King Crimson group and one album of the old stuff. And it's very good to look back on it and realize that the work you did together was very good. At the time, it was such an intense experience, kind of sobering, and kind of hard to deal with. You weren't really sure. At least, that's how I felt about it. I think, at the beginning it was thought that maybe my style of songwriting combined with Robert's sensibilities would make a more pop-sounding band. But I never really thought of that myself because I never really thought of King Crimson as a popular band. I really felt that we were still making the traditionally select, elite kind of music that King Crimson were noted for. During all these years as a sideman, however, Belew's desire to put out his own music had not gone away. "I knew I had to be patient. I knew that I was doing things that were going to lead to that. I always saw all those sideman gigs as a good opportunity to learn more things, and a building block toward getting to the point where one day someone like Chris Blackwell [head of Island Records] would walk up and say, 'What do you really want to do?' And of course I would say, 'Well, what I really want to do is make my own music.' And he says, 'Well, why don't you join my record label?' And that's exactly what happened. In one day's time I suddenly had my solo career. It has to happen naturally. You can't force it on people. "And so I started working on Desire Caught by the Tail. For about the first year away from King Crimson I had no desire to be in another band. I thought, 'That's useless; I'm not going to try that any more. I'm really enjoying doing this kind of music, on my own, alone with just an engineer.' And then all of a sudden I just thought, 'Hey, wait a minute. I do enjoy being in a band. I do really enjoy the exchange of ideas and so on.' So, I tried to picture the band that I felt best about and it ended up being the friends I'd known for ten years, people I knew and trusted and loved, and they felt the same about me. And I felt that, really, we could make some great pop music. So then I decided to delineate between my solo career being the more avant garde music and a career with The Bears as a pop band. "Now, I have other people writing with me. I have an exchange of ideas, I have a live, touring band that can go anywhere and please people and draw crowds, and I feel good about having both sides. If I could generalize the type of audience I think I have appeal to, I think it's more of a thinking audience and more of an emotional audience than, say, a physical audience. That's why a lot of my music doesn't have to be danceable to work. "One of the reasons I created Desire Caught by the Tail as a full instrumental album was that I felt it would give the audience a better chance to imagine their own scenario for the pieces of music. As soon as you put lyrics on something you say, 'It is this.' I love lyrics, but I just decided that I'm going to devote my lyrics to Bears tunes and things that are songs and born out of songwriting, whereas the Desire album, to me, is more compositional. It has to do with creating environments for people to listen to, and you should be able to sit back and imagine your own setting there."

Or, to put it another way, you could say that each song immediately evokes a movie, I suggest. Adrian agrees. "It's very cinematic music. I tried to make it that way, in every step of the way—in the production of it, and the way it's mixed, and the way all the instruments sound, and the events that come and go throughout the music. It's all meant to be cinematic. It's meant to fill your imagination, and for that reason I knew all along it wouldn't be commercial. People don't want to do that; most people don't want to think about music, they want to dance." But you don't have to sit down and think about Belew's music—just hearing it fills your mind with images. "I think my music has a built-in signature, because there are certain areas that I've tended to go to. I mean, I like backward sounds... there are certain types of sound that are more attractive to me. You could probably look at it like colors. Some people are more attracted to one color than another. I think those things tend to become your musical signature because you do them more often. When I'm working with sounds a lot, I always find, 'Hey, this is similar to the sounds that I like.' I feel very much that my music is a continuum. I'm breaking new ground, but at the same time I'm always relating to specific areas that interest me and just renewing them, and refining them, and seeing them a different way." One of the first things this writer noticed about Desire Caught by the Tail was a very classical feel running through a lot of what Belew is doing. Is that what he was after, I wonder? "That's correct I'd say about 80% of the time. I do allow myself a lot of space for surprises and things to occur I didn't think of. That's always one of my favorite things. With all of this technology, it's really easy to surprise yourself and find something you wouldn't have thought of [otherwise]." One of Belew's greatest instrumental triumphs is "Tango Zebra"—very flamenco picking, very flamenco feeling, but with sort of African rhythm undercurrents. But then, the strings are sweet and authentic-sounding, there's a little atonal mathematical progression thing going on, too. "The thing I like about 'Tango Zebra' is the picture it draws for me; it's more of a George Gershwin-ish era music. Not that it sounds like Gershwin, but just that era of music where they used a small section of reed players; and, you know, it's basically a small orchestra with maybe 18 or 20 instruments in it, including, say, a single percussionist and maybe three or four reed players. And that's how I approached it, as though there really were members in this orchestra and I had to produce for their instruments. So their parts are played throughout the music in a similar way to the way you would orchestrate that kind of music. "I first wrote it on a dobro, which is a metal-bodied acoustic guitar, because I felt that if it worked that way, it would be a lot easier to work as a holistic piece of music. I had to learn the parts I wanted, and I played the whole part on the dobro all the way through—seven-and-a-half minutes. Then I went back and just started doing all the different sounds and thinking, 'Well, what would the orchestra play here?' And putting those sounds in there. All the percussion sounds are guitars as well. In fact, almost all the sounds on the record are guitar. There are exceptions, though. When it really sounds like a triangle, that's a triangle—it's really hard to reproduce that on a guitar. Then there are a couple of instances where I use a little laughing box, and I use a little toy guitar in one section. The most I ever used in the way of percussion was just a bass drum, a snare drum, a couple of cymbals, a triangle—I approached it as an orchestral percussionist would do. I also used an African log drum. My idea was to let these natural acoustic instruments offset all the electronics. I thought it was important to keep that acoustic sound overall. "To mix the sound, we put a concert-room hall sound on it so that it would sound as though it was a whole orchestra sitting together playing, particularly for the first side, for songs like 'Tango Zebra' and 'The Gypsy Zurna.' That is one of the things I wanted to do, to have music that is constantly unfolding in new ways. Every now and then it will go back and reiterate something. The ending of 'Tango Zebra' is the same as the beginning, for instance. But a song like, say, 'Portrait of Margaret'—apart from the drums that are continuous throughout and don't play anything different—everything else in the whole song is completely ever-changing. That's how she is, she's a very moody person, so I wanted ten different moods in the course of four minutes. The music still has to be very human for me. The things I write about and even like to think about are humanistic values. The technology is only there in the same way that a painter has an airbrush."

So does Belew feel the way a lot of guitarists do, that a guitar is a "real" instrument, and somebody who uses electronics is just some twerpy little knob-twiddeler? "Well, I can play regular guitar and it was important to me to be able to do some of that on this album. And that's why I say, for instance, 'Tango Zebra' was written on an acoustic guitar. It is a piece of music for guitar without any electronics first, and second it is orchestrated with all the technology and available sounds that I love. So I would never want to shut myself off from either side of that, because I would feel that to be pretty stifling and really kind of stupid. I have read a few guitar players' comments where they said, 'I'm never going to do that kind of stuff.' And I think, 'Poor you.'" There is also the feeling amongst many of today's musicians that if you use something like a synthesizer, you're not really producing music. Surely creating music is the creative process itself, and that is more important than how it's actually produced. "I wouldn't say how I produce it is irrelevant to me," Adrian commiserates, "and it is one of my great joys, picking out how to get the sounds that I need. But essentially, it is all for the same purpose, to create. In this case, I had various pictures of what these songs needed to sound like, and so I had to design the technique to produce them. And some of the techniques we used are pretty bizarre. For the drums on 'Tango Zebra' I had this metal-bodied dobro I was mentioning, and we had percussion pickups on the body and ran the tape at different speeds to create different-sized drums. It sounds like anything but a guitar, but it is an acoustic guitar. When I say 'we,' I mean my engineer, Rich Enhart, and me. Between the two of us we concocted lots of unusual ways of creating sounds. Not all of them are synthesized, not all of them are modern technology. Quite a few of them are just simple little things that have been around for years." But he doesn't use sampling of so-called "found sounds" and then process them electronically. "No," Adrian says, "I did none of that because I had such a wide palette of available things to do. It's a lot more fun for me to create a sound from any source than to sample a sound that already exists. I was very careful to make up my sounds. I felt that was the only way to get the proper character out of them. If I needed a bass clarinet, I sat down and tried to figure out what the bass clarinet sounds like. As I said, it's a long process to do that, but then my bass clarinet has its own little character, rather than just being a sample of a real one. With so many of the sounds you hear, you associate them with some electronic means of doing that, and in a lot of cases they're really a pretty normal means. I mean, a guitar feeding back is something that's been done for years. Though there is one sound on the record that's a wood-panelled door with percussive pickups on it, and I would play it with different sticks and scrape it and do things. We'd run that through a delay and change the timing of it, and it's a very unusual sound. That is used in 'Portrait of Margaret' as part of the drum track." 'Portrait of Margaret' is Belew's most solidly rhythmic song, and it makes me think of the mother's heartbeat—more human, in a way. This piece could actually be a dance club hit. "I wish it was," he says without hesitation. "The idea of 'Portrait of Margaret' from an arrangement standpoint was to create a drum groove, the only time we have that on the record. I always thought of it as very danceable, but because it doesn't have words... People tend to shy away from instrumentals these days. It's really unfortunate. But the idea for that song was really to have something you could dance to, that had a relentless groove that never did anything different, and then to have on top of that an ever-changing set of things, from birds to whales. The whale sound is a guitar run through an analog delay, a delay they no longer make—it was a Roland unit and you could actually change the pace of delay with your foot as you played it, and in doing that it makes it squeal all over and makes it sound like a whale. I discovered that, and then shut off the original guitar so that you could only hear the effected side." "Laughing Man," his most instantly visual piece on the album, almost suitable for making a video for MTV. "I think you could for the first half," he agrees. "The piece is in two halves, and the first is happy, with a sort of accordion-type guitar. A lot of these songs were different ideas I derived from painting and things," he reveals, confirming the underpinning of visual effect in his music. "I've studied a lot of Picasso and Miro, whose painting has really affected me, as well as their lifestyle. I mean, the way they worked was the way I tried to work on this album, getting up every morning, having my coffee, going into the studio and not thinking about anything but this art and trying to realize it. "As for 'Laughing Man,' it's a Miro-ish kind of thing to me, because he has a lot of strange, carnival images—very carnival scenes that are somewhere between ecstatically happy and melancholy. And so I tried to make that music express both those feelings. By the time you get to the end of the piece of music it is pretty melancholy, but it starts out pretty happy. The other piece of music that always stands out to me is the one called 'Guernica.' Now, 'Guernica' is a great big mural that Picasso painted about war and chaos when the town Guernica was bombed [in the Spanish Civil War]. It's a beautiful, unbelievable painting, and halfway through making this piece of music, which is only two minutes long, I realized that that was what it was about, it was about war and chaos. And there are some horrifying sounds in there, to me—it scares my kids." Yet, it's a rare thing for any musician to say that he's been influenced or inspired by painters. "Well, that was really where this album came from," Adrian reveals. "I love the romance of that idea, that someone gets up and they start painting every day, and they put it aside for a while and they paint something else, and they come back to it. And they continue to work on it with no real concern for its commercialism—they just have this burning desire to make this thing work, to realize this vision that they have. When King Crimson was over, that was kind of what I was left with. I had this desire to visualize the paintings that I had. I had read so much and was really inspired that way about Picasso's life, and it would really make me feel like there's a lot more to music than just being on television or making money or being popular or being known. It is that you have music inside you that you want to get out, even if only five people ever hear it. "That's how I feel about his record. I think it's a little bit easier to be autobiographical if you are writing a song. For any number of songs I've written, I've felt, 'This is about my relationship with my wife, or this is about my children, or something that affects me.' But I think it has to go a bit deeper if you're just writing music—it's a bit more subtle. This [record], to me, is the best expression of my own personal feelings that I've done yet." With Desire Caught by the Tail in the stores, Belew has turned his attention to his other ongoing project, The Bears. Work on their record is currently well underway, with Belew again acting as producer. The aims and intentions of the two records differ, though, as do their means of production. The Bears' record is all digital, because the limitations of digital technology do not affect the requirements of the more pop-oriented Bears LP the way they do Belew's more experimental solo efforts. "I still like some of the analog stuff myself," he explains, "because there are still things you can do with the analog that you can't do with the digital. Editing is not so easy, for instance. One of the techniques I use a lot is vari-speeding, where you speed the tape up to different rates, or slow it down, to get different sounds. You can only do that marginally with a digital machine; you can't do that nearly as far up or down as you can with analog. Another technique I use is a lot of backwards recording, and you can't do that at all with a digital machine, yet. The studio that I work at, called Royal, has a 32-track digital machine and two 24-track Studers. We slave them sometimes. Or else we just drop things off onto the 24-track, turn them around backwards and fly them back into the digital machine and mix. We haven't really used it for extra tracks yet. We use them mostly for some of the techniques that you can't do digitally. And you don't notice the difference at all, because just doing one little generation of tape is nothing, really. "The work with The Bears is very different from the work with the new solo album, where everything was done in layers, of course, because I was the only player. But, in fact, producing is not hard for me—I can hear each track separately in my head. I really enjoy it. I would like sometime to tackle someone I don't have such connections with—that's in the future for me, I think, because I do enjoy producing. The part of it I enjoy the most is actually the arranging. Like I said, all my life I've listened to records with an ear toward why that harmony was put there and why the drums sound that way and why there is reverb over here..." Which just goes to show that if you have an inquiring mind, the music world can indeed be your oyster. |