| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

Aerosmith Interview by Joy Williams

But from that point on, Aerosmith started breaking ground as they set out on a path very much their own. By the middle of the '70s, Aerosmith were the rulers of rock in America, excelling at all the excesses of the day. But by the beginning of the '80s, some of the band members seemed unlikely to be living, much less flourishing, in the early '90s. "In 1978, Aerosmith represented the living spirit of American rock'n'roll," says David Krebs, Aerosmith's original manager. "To see them destroy themselves through immense disregard for anything but self-indulgence was a tragedy." It is perhaps fitting that a band which would set off on something of a permanent vacation together started its life in a summer resort town. It was in Sunapee, New Hampshire, in the summer of 1970, that Anthony Joseph Perry and Steven Tallarico met at the Anchorage, an ice cream parlour where Perry was working. By this time Tallarico (or Tyler as he would eventually become known) was, at least in his own mind, already something of a rock star. He was an ambitious veteran of bands like the Strangeurs, William Proud, and Chain Reaction, the latter of which had even recorded and released a single. Perry and his bassist friend Tom Hamilton, meanwhile, were still very much at the local bar band level, playing with groups like Pipe Dream, Plastic Glass and, finally, the Jam Band. Perry remembers being intimidated at first by Tyler. "Steven sure looked like a rock star, and he definitely acted like one," he says, "so we just assumed he already was one." Perry and Hamilton didn't require a lot of convincing to join forces with Tyler.

Early on, Tyler considered both drumming and singing with the new band, as he'd done in previous groups. Eventually, he decided it made more sense to concentrate on just being the front man. The group signed on two acquaintances of Tyler's-drummer Joey Kramer, who was born in the Bronx (New York City) and had recently studied briefly at the Berklee School of Music, and guitarist Raymond Tabano. The five soon moved in together, into a dingy three-bedroom apartment at 1325 Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. Tabano was eventually replaced by Brad Ernest Whitford, a Massachusetts native who'd also studied at Berklee and played in bands like The Teapot Dome, The Cymbals of Resistance and Justin Tyme. Before long, the group decided to call itself Aerosmith, an imaginary band name that Joey Kramer says he had written again and again on his textbooks to pass time in high school. The early days of Aerosmith, as described by those who lived through them, sound something like the Monkees on drugs. They lived under one roof, cooked up a cheap concoction of brown rice and vegetables, got high and watched The Three Stooges, and worked day jobs: Tyler at a bakery, for instance, and Perry as a janitor at a local synagogue. They listened to a lot of Jeff Beck, Cream and Deep Purple records and began to chart their own course. "I think what we wanted to do, without ever really saying it, was to be the American equivalent of all the great British bands like Cream, the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin," says Hamilton. "They were all so classy and powerful sounding. We couldn't think of an American band like that. We wanted to be the first one." Aerosmith started to find its own sound as it played unglamorous gigs at area high schools and fraternity parties, or anywhere else where somebody would come up with the $300 and the box of malted milk balls that they requested for their services. After giving up their day jobs, however, Aerosmith started having serious financial trouble. The most immediate problem was that the band was running out of places to rehearse. Eventually, the manager of the Fenway Theater in Boston let them use its stage off-hours, and he invited Frank Connelly, the man who'd brought Jimi Hendrix to Boston, to hear the band. Connelly immediately became Aerosmith's manager, but since he understood he needed someone with more experience in dealing with the record companies, he went into partnership with Krebs-Leber.

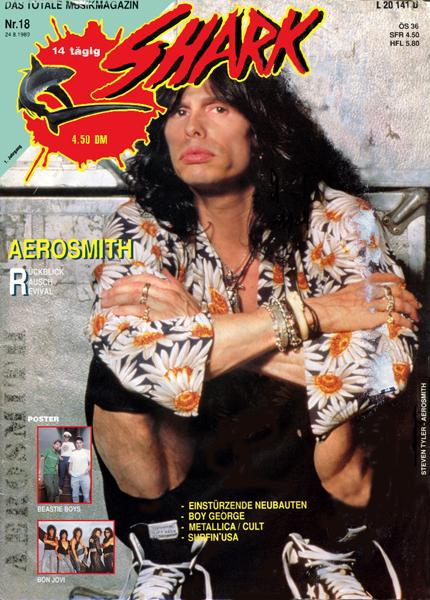

Wasting little time, the new managers invited two labels to see the band play a showcase at New York's famed Max's Kansas City. Clive Davis, then-President of Columbia, found his way into the club's backstage area after the show, where he told his label's future best-selling act, "Yes, I think we could do something with you." Aerosmith was hardly an overnight hit, except in Boston where the band had already developed a strong following. The third time around proved to be the charm for Aerosmith. Toys In The Attic—recorded at the Record Plant in 1975—was the album that found Aerosmith getting its wings for real. The record became the group's first platinum effort, and its acceptance helped both of the first two albums go gold by year-end. Now headliners in their own right, Aerosmith took time off from the road to record their fourth album, Rocks. "We were doing a lot of drugs by then," recalls Perry, "but you can hear that whatever we were doing, it was still working for us. Sadly, things didn't keep working quite so well for long. The band's fifth album, Draw The Line, was the first on which the band paid a musical price for its members' excessive and ultimately destructive lifestyle. "We'd gotten to that dangerous point where we could afford our vices," says Tom Hamilton. "We all had our mansions, our Ferraris, and our never-ending stashes." The album, released in December, 1977 and which cost over $1 million to make, simply failed to live up to the great expectation that their last two efforts had created. "From the inside I didn't think anything was wrong," says Perry. "But from the outside you could see everything. The focus is completely gone. The Beatles made their White Album; we made our blackout album. "Things came to a head during the making of Night In The Ruts. The sessions once again dragged on endlessly and expensively. Perry was getting fed up with the state of the band, and he announced his intention to do a solo album. The prospect threatened Tyler, who was by this time, in his own words, "totally FUBAR—fucked up beyond all recognition"—on heroin. Relations between Tyler and Perry, already quite strained, worsened radically. "If we were in a different space, we'd have killed each other," says Perry. Perry quit, and Aerosmith went back into the studio with Jimmy Crespo as the new guitarist. The band attempted to tour in support of the album, but shortly after the tour got underway, Tyler collapsed on stage. As if Tyler weren't in bad enough shape, a serious motorcycle accident laid him up in a hospital for a significant part of the next year. Meanwhile, Whitford went off to record an album with ex-Ted Nugent singer/guitarist Derek St. Holmes. That project came together so easily that it made it clear to him how absurd the situation with Aerosmith had become. He, too, decided it was time to jump ship. Another guitarist, Rick Dufay was brought in to replace Whitford and eventually Rock In A Hard Place was released. But this would be the end of an era: the last studio album that Aerosmith would record for Columbia Records. At the time, it looked as if it might simply be the end. Indeed, before things got better for Aerosmith, things got even worse. Perry ended up flat broke, living for a time in a Boston boarding house. Tyler, meanwhile, had taken up residence in a Manhattan hotel that he favored because of its access to the heroin dealers on Eighth Avenue. Amazingly, however, Aerosmith reformed and returned, hurtling into superstar status again in 1987 with Permanent Vacation. The rise and fall of Aerosmith represents rock history at its most genuinely inspiring. With the backing of new band manager Tim Collins, the band has managed to clean and sober up its act, and is now reaping the rewards. For the second time, they have popular acclaim, and for the first time, critical acclaim, especially as they followed the multi-platinum comeback album with another, 1989's Pump. But it wasn't Steven with whom I recorded the formal interview back in '89, it was Tom Hamilton—the sounding board and mediator—who filled me in on the background to the ups and downs of Aerosmith.

Q: I read the other day about a psychologist who says that he can discern your entire attitude toward life by your earliest memories. So, what are yours? TOM: I have this memory—I must have been about 4 years old—of my brother getting his first guitar, standing in the living room with his legs spread apart, playing some Elvis song. Right around the same time, I got this little electric toy organ for Christmas and I learned "The Marines' Hymn" on it. When I was really young I listed a lot to The Ventures, who are an instrumental guitar band. I used to dream about being in The Ventures, being up there playing their songs. Come to think of it, even when I was a little kid, I was curious about the bass guitar, because I used to get these "How to" records by The Ventures, and they came with this instruction book that had the bass part laid out, and it felt really great, those low notes. I started learning bass parts and comparing them to guitar parts pretty young, so that probably had a lot to do with when I got into my first band, I just automatically slid into the bass. And I like the power of the bass, it's kind of like this big freight train, cruising along. Q: Who else influenced you? TOM: The Beatles. The Beatles were just gigantic to me—that whole experience of seeing them on Ed Sullivan (TV show). Then, I had to go through this whole traumatic decision over whether I was going to be into The Beatles, who had vocals, or stick with my mainstays, The Ventures. I decided The Ventures had to get in the back seat. With The Beatles such a gigantic, radical change came over the pop music business! I know that it's really, really hard for people who weren't around then to understand just how momentous it was; it's just there was never anything like it before. And all of a sudden these guys came, and they had long hair, and.... You know, rock'n'roll had been on the back burner for a few years; we had all these softies, because Chuck Berry got busted, Jerry Lee Lewis married a 13-year-old, and Buddy Holly died. And that was the end to the really tough era, where it was nasty and it was risky to dig it. After that, there was all this fluff. Then, all of a sudden, The Beatles came along and it was like a whole new revolution in pop music. Q: Yeah, the young English bands went back to those early guys, and even back to the blues greats like Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf. But still, it's fascinating when someone comes up with something really different. TOM: Oh, yeah, it's not like The Beatles sat down and drew out a plan. They learned the music that they loved, and they went to Hamburg and played five sets a night for months, and got really good and really tight and really professional, and wrote their own songs. And exploded. Just exploded! And I got totally swept up in it. I had every Beatles magazine that you could buy, I had all The Beatles bubble gum cards, not to mention their records. I used to drive my friends out of the house, because I'd get the latest Beatles single and play it over and over and over.... Q: But that's how something sinks into you and becomes part of you, rather than being just something you learn and copy. A lot of people can learn the notes, they can learn to copy something. But what you're talking about is the kind of thing where it just becomes part of you, and it then comes out in its own way.

TOM: Because it sinks down into that pit where your emotions are. And once it's touched that area, it's there forever. Then, the next time you hear it, you're going to recall your emotions. Even picking up a Beatles single and looking at the colors of the label will bring me back to the way I felt when.... That music wasn't just entertainment for me, it was the sound track of my life. Everything I did was according to whatever Beatles song or whatever Stones song I was getting off on at the time. Q: You just mentioned the Stones. There's always been this split between the brighter, popier Beatles music and the darker, nastier Stones thing. Did you feel that, too? TOM: I don't remember really feeling that need to show my allegiance to either one. But I remember looking at a picture of the Stones and thinking they were the ugliest people, trashy-looking and sloppy. And their music was the same, but was it ever great! The Stones, they grabbed me; and I didn't know why it was I liked them, but I had to love their music. Q: But then you finally got to where you could create your own sound track. TOM: Well, that's like, you've been eating all this food and your musical body is built on that food. So when you start coming up with your own ideas.... You know, there's an old expression, "You are what you eat," and it's the same for music as it is for food. Q: So what did you do with all this musical food? Did you go through the usual thing in high school, copy bands and such? TOM: Well, Joe (Perry) and I used to get a band together every summer—I've known him since I was 14 or 15. We put a band together called The Pipe Dream when I was about 15. And then at the end of the summer I would go back to school; and he was a "summer kid," so he'd go back to Massachusetts and go back to school. The summer after that we put another band together, called Plastic Glass, and then the two summers after that, we had a band called The Jam Band. Q: Did you live for the summer? TOM: Oh, yeah! We each spent the winter learning songs and just thinking about getting back up there and playing. I listened to a lot of records. I didn't take lessons, I just learned from learning other people's songs, and started to pick out little elements that I liked, and throwing out elements that I thought were boring. Q: Going back to your musical evolution, you knew Joe from way back, but where did Aerosmith come in? TOM: When I graduated from high school in 1970, Joe and I went to put a band together. Actually, for the whole winter before that I had been realizing, and Joe and I had been talking, "Let's face it, we're going professional." So, finally, I graduated from high school, Joe and I put a band together that summer, and at the end of the summer Joe and I said, "All right, let's move to Boston and put another band together, one we're going to try to make our living with." And right around the same time, Steven (Tyler) and his bands had been coming up to the area where I lived, and playing. As a matter of fact, they had been doing that for a couple of summers; and when they came up, it was a huge event because they were this New York band that had recorded records. They were professionals.

Joe and I a lot of times couldn't get in where he was playing, so we'd actually hang around outside and listen through the walls. But then Steven got himself into a couple of bands that didn't really go anywhere, he was involved with people who weren't as dedicated and committed as he was. And he started getting frustrated. So, during that last summer, he and Joe started to get to know each other and started to compare notes on what they wanted to do for the future. And I started to get to know Steven, finally, and we found that we had a lot in common as far as what we wanted to do. So Joe and I proceeded to go on down to Boston and start looking for drummers and auditioning people. Finally, we got back together with Steven, and he said, "Let me play drums." So, OK, we had a 3-piece band. But we never actually got together and played as a trio, because all of a sudden, along came Joey Kramer. So Steven, Joe and I were at a party one night and we said, "Look, why don't you go back to singing lead?" 'Cause we'd seen him as a lead singer before, and he was definitely made to be up there. Q: There's something about a frontman.... TOM: Yeah. They're born. They're not made, they're born. So Steven says, "Yeah, that's great, why don't I do that?" We added one more guy, Ray Tobano, who was a very demanding person. He wanted things to go his way, and his level of playing really didn't justify all the tantrums and fighting that went on as a result of his personality. So we fired him and replaced him with Brad (Whitford). We'd started writing our own songs shortly before, and putting them into the set. Either Joe would come in with a riff and Steven would expand them and add vocals, or the band would be jamming and Steven would hear a riff pop out that somebody'd just played off the top of their head, and stop everybody. We'd pick up that riff and start playing that over and over again until we thought of another part to it and keep expanding it that way. Steven is that kind of musician who can take his melodic ideas and figure out how to express them on any instrument. He's a real good keyboardist and a good drummer. We avoided clubs. Steven had a booking agent, and this guy was able to get us gigs in high school gyms and frat houses. We would play three sets a night instead of five sets. In those days, a club gig wasn't a one night deal; it was five or six nights in a club. You'd make great money, but your singer would blow his throat out, especially a singer like Steven; he basically does all the singing, and he's not the kind of singer who hold back and pace himself. He knew that if we did those club gigs, it would ruin his throat. But there's a fork in the road there. You can either make a good living playing those steady gigs on the small circuit, or you can take a chance and write your own material and play places where they'll let you play your own material. Actually, we'd gone for a while without playing a gig and we were on the brink of being evicted, and we were in a local music store asking around about a place to rehearse and this guy said, "Go ask my brother; he stays with this manager of the Fenway Theater," John O'Toole. Then, one day some semi-famous band was supposed to play there but they canceled out. We happened to be up in the balcony waiting for them to go on, and all of a sudden the manager came up and said, "Hey, you guys, I need you to play." So we lugged all our gear up onto the stage and played, and the audience loved it. The next day John said, "There's a manager here to see you." We couldn't see him, the lone figure in this big theater, but we said to ourselves, "OK, start playing, he's out there." So we played for about half an hour, the lights went off, the curtain closed, and he was gone But he left behind a management contract. It was pretty exciting—that was really a scene out of some movie! So he started to manage us, but he realized he didn't really have enough experience in getting bands record deals, so he called Lever-Krebs in New York and they had us come down and play at Max's Kansas City in front of all these record people, and they liked us and we got signed to CBS. And it was weird, because we'd been preparing for that moment since we'd got together, so we were ready. We recorded our first record (Aerosmith, 1973), recorded all these songs we'd been playing for a couple of years. It came out, and failed. Q: How'd you feel then? TOM: Pretty bad. Because we thought it was the best record ever made. But Lever-Krebs knew what to do. They got us a booking agent, got us out on the road with bands like John McLaughlin, The Kinks, and eventually Mott the Hoople. That tour with Mott the Hoople, after our second album was released (Get Your Wings, 1974), really got us up there, got people liking us. Then, some time during the recording or initial release of our third album (Toys In The Attic, 1975), the song Dream On caught on with a whole bunch of radio programmers, and it became a big hit two years after it was released. Q: So here we had a critical turning point in the life of a band, where you go from struggling to make it, to being big stars. That can do some pretty weird things to your head, and many bands find themselves in trouble, Aerosmith among them… TOM: We started doing really well after that and our third album. With Rocks (1976), our next album, we started doing some really big headline tours and eventually made enough money so that when we made our next album, Draw The Line (1977), we started getting into some of the destructive stuff. That was the atmosphere of the times, and we were burnt from constantly touring and constantly recording. Draw The Line took 67 months to record, as opposed to three months for our earlier albums, and it just came out kind of unfocused. And it was a step down. But we had a nice, healthy denial system; figured everybody else was wrong, went out on the road, and we did great there. However, that nasty relationship, that "healthy denial system," and the substance abuse that earned Joe Perry and Steven Tyler the sobriquet of the Glimmer Twins continued to take its collective toll through 1979's Live! Bootleg and Night In The Ruts, where Joe Perry bailed out and was replaced by Jim Crespo. Tom found himself as "the guy who is always in the middle in a lot of arguments-you know, always mediating and examining each side. I wound up with my phone ringing, hearing about one guy's misunderstandings about the other guy's misunderstandings. In the old days, just before we broke up, I'd get a lot of calls from Joe and a lot of calls from Steven."

On the Permanent Vacation tour, I had remarked to Joe Perry how he appeared to be much less depressed than when I'd interviewed him back in the days of The Joe Perry Project (1983), after he'd left Aerosmith. He looked at me and said, "Well, you know, I quit drinking, and the depression went away." But I've noticed that it's not always that simple. Some "reformed" alcoholics and/or addicts continue to have the same lousy attitudes towards life and other people as they always had. "That's right," agreed Tom, "it's called being 'dry drunk.' And we couldn't put Aerosmith back together again until the majority stopped pointing to the minority and saying 'It's your problem,' and acknowledged that we all had a problem. It took years to learn new attitudes. Joe and Steve don't call me all the time now with their mutual misunderstanding, because we've had to be a lot more straightforward with each other, and talk about what's going on. We're all clean and sober now. We finally realized that we were tired of working at about 40% of our ability, and we had to change. And, you know, I dreamed of success when I was a kid but the first time around, I took it for granted. This time around, I'm savoring every minute of it." |