| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

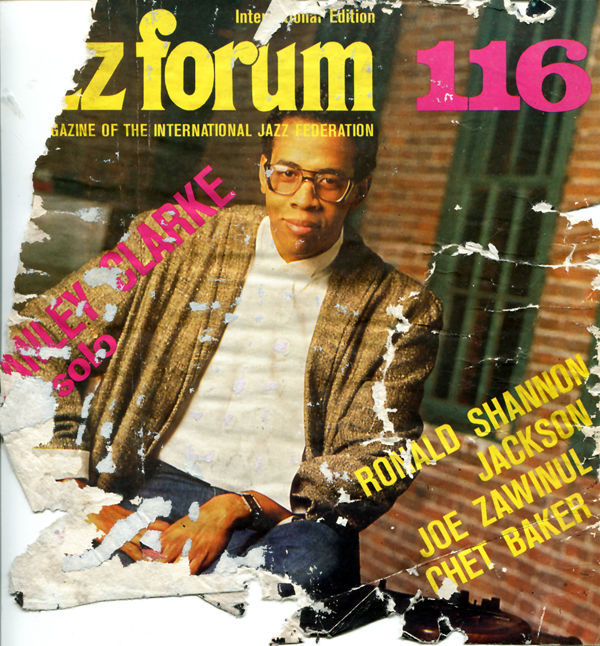

Stanley Clarke Interview by Joy Williams

And so Stanley Clarke, who within just seven years was to be hired by Horace Silver for a six-month tour of the United States that turned out to be "the bass line heard 'round the world," chose his instrument and set his destiny because he was big for his age. "It's funny," Stanley reminisced, "the music teacher was a little, short Italian guy and he was trying to get me to gig a violin. But he said, 'No, that's not going to work. Cello? No, that's not going to work.' Because for kids they have these little tiny instruments, but when I was 12 and 13 I was almost as tall as a man. My hands were definitely that big. So my teacher just said, 'that over there.' "Part of the desire to play music was already there. It's like a need. I think it's because of my mother, an accomplished singer and painter. So that was always there; it was always around me. I wasn't walking around particularly thinking about doing things other than music. The only other thing that I liked was sports." Q: You've changed a lot over the years, starting out as a jazz purist but eventually moving into popular music, of all things. You like melody a lot, too, which is sort of different for a bass player. STANLEY: I've always liked melody. I really think I could've played any instrument, actually. But I picked the bass and my music just goes through that. I had music teachers all through junior high school and high school, and then I went to college, The Philadelphia Musical Academy. I finally made my way to New York to make my statement in the world of music at 19, because I never finished college; I left at the beginning of my fourth year. I just went to New York, I wanted to try out for this band. It was a lot of fun, I had a great time, [though] it was tough, very tough. But as far as my attitudes about music at that time, I was a serious purist, a jazz purist. Actually, I had to be in order to be able to go through the whole jazz circuit. When you're looking back, the guys that'll say, 'Well, you know, if I had to do it all over again, I'd change this and I'd change that'—it's really hard to say that, because probably the success you're having today is due to some of those attitudes, as weird as they may have seemed. I'm a funny person in that I really don't mind anybody's attitude. Even people who have edgy attitudes, just as long as I feel that no one is getting hurt. Q: But what led you to change your purist attitude about yourself and your music? STANLEY: Well, I was actually starting to be more comfortable, and then be more like myself. When I was being a purist, I wasn't really being myself. I had taken on this attitude to get myself through a couple of things. But once I'd been in New York for a year and done a whole bunch of studio work and played on quite a few albums, I felt a little more stable and into the music world. Then I just starting projecting some of the things that I would normally project. I've always been one to listen to all kinds of music, still do to this day. I have to say I just refuse to be narrow, as far as what I take in from the world. Q: Bass playing has changed remarkably, and in many ways, since you first started playing. STANLEY: It's no longer in the back. Or I'll put it this way: every instrument has a significance attached to it. What I mean is, most people think that everyone who plays piano is intelligent, the drummer's usually dumb, and that the bass player's just slow, the guitar player is the star, and the singer has the biggest ego. And some guys get into that. But fortunately, it's just not true; some of the dumbest people I know are piano players. (laughs) Yes, the bass has changed, partly due to just attitude change about approaching the instrument. Q: It's also been partly due to particular people. Paul McCartney's been credited with bringing the bass up front, and you've been influential due to your styles and techniques, too. STANLEY: [Acoustic] bass is definitely my main instrument because I actually like it—because it's large, it has a nice sound to it, and you have to take really good care of a bass. There's a whole ritual, just to get the bass together, to play. When you're playing classical music you have to wipe the bow down, you have to touch the bass a lot. You can't just pull it out of the box and play it; you have to wipe it down, clean the strings, just make sure all the working parts are there. Q: It's difficult to explain what a musical instrument becomes to you. STANLEY: Well, for a man, an acoustic bass could be like a woman. It kind of borderlines on that sort of thing. Q: There are two kinds of people. There are those who, when presented with something new and strange will say, 'I don't like it,' and walk away. And there are those who are attracted to what is different. Being attracted to what is different will lead you to experiment more as an artist. STANLEY: Well, you know, a lot of people feel that they have to love something in order to experience it. I completely have a different view, especially when you're viewing art. There's very few things that I really, truly like, that really get me in the gut. But, I definitely have the ability to experience anything. I won't even go so far as bringing in my own likes about it; it's just a pure observation. A person doesn't necessarily have to look at something and then make a decision for himself whether he likes it or not. You can just look at it and move on. Believe it or not, that's the way most musicians play music, anyway. If you sat down with another musician and in your mind you're thinking, 'I like that, I like that, I don't like that,' it wouldn't work. What musicians do... you're playing, and the notes are going. Then, maybe if you've taped the thing, you can sit down and listen to it and see if it's any good. But I personally like to just play and move on, go play something else or listen to some music, put that down and go listen to something else. There is certain music that I personally like, that I put on—I usually like to put that on while I'm doing certain activities. In other words, I'll give some music a purpose. That's probably what a lot of people get confused with, when they listen. Like a normal guy—a kid—he'll put on a record and the record has to fit in with his clothes, with his buddy's clothes.... I mean, so many people like music because of so many reasons other than themselves, and they're not even aware of it. To be real honest, when someone tells me, 'I like that'; or, 'I don't like that'; or 'that was boring,' it's very rare that I'll take that person's consideration that he has about the music to heart. Because I'm not sure whether the person really feels that way, or whether he's basing that on some arbitrary thing that has nothing to do with the music he's listening to, or even better than that, nothing to do with him! Q: You're sitting on opposite sides of the looking glass. That's sometimes difficult for the musician to deal with, because you are trying to reach out and touch the audience. I find in choosing music for myself, I'll choose a particular record not only to fit the mood I'm in, but also to take me to the mood where I want to go. STANLEY: Absolutely. When I'm playing live, I definitely hope I feel better when I come off the stage than when I enter. Q: It's been found that music actually causes biochemical changes in our bodies, which in turn affects our emotions, and different music causes different chemicals to change. So, you are literally playing with our emotions. STANLEY: Sure. I don't think musicians really think of the emotion, but that's what we deal in. Like, 'yeah, we have a sad song here,' or 'this is a real mover.' Basically, all you're talking about is emotions, there.

Q: How did your rather unique popping technique come into being? STANLEY: I first heard it on a Sly & The Family Stone record. Larry Graham, his bass player, used to pull the strings.... You could tell this was sort of a side thing, that he hadn't really done much with it, but I thought it was a great thing. I started doing it because I liked it; then, I guess I have to say, I just refined it so that you could play it in all keys. Q: This desire to experiment and explore is part of what has brought you from there to here; it's consistent throughout your career. You keep changing. STANLEY: Yeah. But there was a period there, when the new wave music was coming in, when everybody was starting to go that way. Even the jazz bands thought it would be hip to get into new wave music; everyone was wearing thin ties.... And then it was pretty locked in. Even more traditional rock bands were looked upon as, 'Ah, that's not really happening.' The jazz thing was like, "Oh, man, you cats are way off!' I remember going into clubs and seeing T-shirts saying, 'Destroy Art.' It was just like, anything that wasn't straight and direct wasn't happening. So, hell, man, it was a rough time for a jazz musician. I remember putting out a record and some guy just completely putting it down because of the fact that I was experimenting on it, or you could tell that I was being creative. See, you have to understand that there are only a few really true jazz journalists. The majority of the writers that review music for the magazines listen to all kinds of music, they're not purists. But the jazz journalists, like Leonard Feather, he wouldn't know Sadé from.... He's a purist; I take my hat off to being that, but there's even a disadvantage in that because sometimes those guys can be a little narrow minded. There might be a record that has a good statement. For instance, when we were coming out with the fusion music in the early '70s—and that was new and innovative—and no matter what he [Feather] said.... A lot of times when new things come out, there's a roughness about it, and he never liked the fact that we were loud and that our records didn't particularly have the best sonics. But they had this new stuff! We were playing jazz styles with classical this and that, very loud. Q: What led to this new style, literally a fusion of rock and jazz stylings? STANLEY: I'd always listened to rock and roll, jazz, acid rock, classical music—always. So it wasn't really a switch in my mind. When I went to New York I played more traditional jazz first because those were the gigs I was faced with, but then when I was able to start playing with who I wanted to play with and also play my own songs—obviously, my songs weren't all traditional stuff and the other stuff started coming out. Originally, I didn't do it for other people. I was playing this stuff mainly for myself. I was just trying to develop some things for myself. Then when I got with Return to Forever we were traveling around the world, and one day I said, 'Oh, there's an audience out there; people actually like me.' And it was like, 'Let's look into this.' Q: But you were violating the rules, and that upsets some people. STANLEY: When Charlie Parker first came out, and even John Coltrane, these guys were hated! These guys were like subversives. My point is, journalists are like normal people; wherever the tide goes, the majority of those people will go. Let's face it, in this world—it's a very crude thing to say, but it's just very true when you look at the facts—there are more followers than leaders in this world. Q: That's probably necessary, or we wouldn't have a society, but.... STANLEY: Yeah, everyone couldn't sit there and say, 'This is my music. This is what I do, and to hell with everything.' We'd have a totally antisocial world. (laughs) Q: Herbie Hancock said he moved away from being an avant-garde jazz purist when he realized that his music had become so esoteric that he had separated from the audience and from the world. So he decided it was time to change. STANLEY: I actually respect Herbie for coming out and saying that. I mean, Herbie is one of the few guys that actually continually stands up for what he believes in. Herbie has a great thing that he said about musicians that have criticized him and guys like myself and George De and people that are known jazzers but who also can do this other thing. Herbie says there's a lot of guys that play jazz but, to be real truthful about it, just cannot play this other music, just cannot play a groove. Some of this funk stuff takes an ability; it sounds very simple, it sounds like anybody can do it, but to actually get it to sound like that…it's an art. All the guys that are criticizing—like Wynton Marsalis and those guys—I would hate to be around to hear those guys playing on top of a groove! Q: Miles Davis said about Wynton Marsalis that he's lazy. He said these musicians sit back and criticize, but it's really that they're lazy; they only want to play one way. STANLEY: He's right. Wynton will change, though. You watch. In another five years he'll change, you'll see. When Wynton came along, the media needed a new, young black jazz musician, because historically that's happened since the '30s. All the important jazz musicians that came along were young black guys, it just keeps along with the history. So, all the guys I hang around with.... I shouldn't really tell you this, but here it is. Our joke is that Wynton's carrying the jazz flag now. Everyone gets that when you're coming up. I remember when I was 19 and everyone was raving, 'Hey this young bass player, yeah.' And they gave me the jazz flag, and I was runnin' around with the flag like a fool. 'Everyone else is a piece of shit, and I'm really the shit and nobody else is nothin'.' And then you see that someone else may take the flag from you while you're sleeping, you know. (Laughs) Because there's another young guy that's just reached 19 or 20 and they give the flag to him. Anyway, Wynton has this flag right now, the jazz flag, and he's doing exactly what everyone else did. Of course, Wynton is probably a little more literate than I was at his age, and he can handle the press better. He's saying the same thing we were all saying, but he's doing it with more effort and more force. But I think something's not working here. There'll be another guy that'll come along. Q: Is that what happened to you when you got tired of playing for a while? STANLEY: Yeah, sure. I realized that, geez, you go around beating your head against a wall—you're real idealistic when you're young—and you think you're saying something that's going to change the world. Believe it or not, musicians actually think like we're going to change the world. Q: But don't you almost have to? STANLEY: Yeah, you have to. The only thing is that only a few can do it, and that's the sad part. I was fortunate enough to be in one of the early one or two fusion bands when I played in Return to Forever, and we did change the music world to a degree. Q: So you're saying that part of making a difference is chance, or timing? STANLEY: Yeah! It isn't like you wake up at 17 and you go, 'I think I'm gonna be in a world-famous group and we're going to travel around the world and we're going to play this music and then thousands of other kids are going to play like me. Q: But it does happen. STANLEY: It does happen. Even with Wynton. Wynton has changed (things); I'll tell you exactly what's he's done. These things that I've said about Wynton are my criticisms of him, but the positive things I have to say about him outweigh those negative things. He brought some respectability back to jazz, and he brought some respectability back to the black jazz musician—because he's literate, black, and he can talk. It's unfortunate that even in music the whole racial thing, as much as most people won't look at it.... What was happening in music is that the whole tradition of black musicians playing jazz, real jazz, was squashed when the new wave thing came in. It was almost like, 'these guys don't even exist, this is not important.' But what Wynton did, and my hat goes off to him—and a lot of times this is what you have to do, and this is what I had to do—is you have to just be far better than everyone else. I mean, there were no other trumpet players—black, white, blue or whatever—that had the technique and the knowledge of the music that Wynton had. And the one good thing about this country is that when you do excel at something and when you are just so fucking good at something, all the powers that be, will say, 'OK, man, you're it. Here's the flag.' When I came up on the bass, for the times, what I was doing was just very different. It's not even a matter of whether it was any better, it was just very different and I was very rebellious on the bass. Hell, I was making albums and I was playing bass solos on every cut, where guitar players and saxophone players would normally do that. I remember one guy came up to me and he thought I was absurd. He thought, 'That's crazy, how could you do that?' But that got me to where I am. Q: If you're very good, it becomes impossible to ignore. And the rules start changing. You don't change, the rules do. It must be awfully difficult to deal with when you're young. STANLEY: But I feel pretty good now about that stuff, because I understand it a little more. Life—time—definitely teaches you many lessons. I can look at it and I can see someone else getting into it and I can predict what is going to happen to them. It's fun. I was fortunate that when I was very young I had my great-great-grandmother still alive; she was like a hundred-and-something—she was around when Abe Lincoln was around. I was like 11 and 12 and she was telling me the real shit. Her whole thing was that she was so old that she could predict things. I'll never forget, the first time she saw Martin Luther King she said, 'You know, that man's going to be killed right after I die.' She was the first person that got me to see that everything that people tell you isn't necessarily all that's out there. Everything that you see with your eyes isn't necessarily it; there are other things. Her parents were slaves, so there was the African hookup there. Q: When you first went to New York, how did you become such a big sensation so fast? STANLEY: I was just really ready for whatever challenges (were to come along]. I started looking for work (as a session musician], and then the calls just kept coming. One of the big lessons that I learned was that not only playing good helps you get on with what you're doing, but your personality, too. I actually think that that's 40%. I came from a family that was not a 'heavy' family; we were pretty friendly, open. I lived in various neighborhoods, from ghettos—an all-black neighborhood—to mixed neighborhoods. I was always around a lot of kinds of people, so I never really tripped on talking to anybody. When I got into playing music, I always tried to make people feel relaxed, because I was relaxed. I used to do a lot of commercials—canned soup, Jimmy Dean sausages, all that stuff. It was just like being a working musician, and I really didn't even have any great expectations about really becoming famous. I just wanted to be the best about what I was doing, because I knew that if I did that, everything would be OK. And fortunately it was. Q: And sometimes it doesn't work. Like with Jaco Pastorius. STANLEY: Well, Jaco had a real complex problem, though viewing it from the outside it's a very simple problem. We used to talk about this a lot with him. He came on in the press and in front of people as being very cocky, but when you sat down and talked with him, you saw that he wasn't sure of himself. He never even knew how good he was, definitely (not]. It was really sad, because there's so many people who know exactly how good they are. (Laughs) He didn't know enough how good he was to feel comfortable. Q: It's a tricky thing, because you have to know you're good, but you have to also realize you're not as good as you could be. STANLEY: You have to leave some space there, and he had this thing. So basically what he used to come on and feel as hip as he thought he should feel, was drugs and alcohol. Q: So you feel he was drawn into this aura that surrounds musicians? STANLEY: Yeah! Of course, man, when I met Jaco, man, he was in school—Jaco's my age. He was going to college, and I was going down to Florida and someone said, 'Yeah, you gotta hear this guy.' And I met this guy, and he was just a kid, like me. Then when he got in Weather Report, he really started changing, when he got into this world of music. I just think that the characters he was hanging around with didn't look out for him. Not to blame them, because you're responsible for your own condition, but he just wasn't fortunate enough to come across someone who would say, 'No, Jaco, go this way.' He was just kind of left to run wild. It's unfortunate, you know. The one good think I've got to say about Chick Corea is that he really cares a lot about his groups, he tries to create a family feeling. I can't say he was the perfect leader, but the one thing that he did that I have to acknowledge is that he would get the groups to feel like they are family, and then you would naturally just look out for the next guy. 'Cause I could've ended up like Jaco, easy. Easy. Any of us could've. Q: It's fascinating, and often frightening, to watch what happens to someone when everyone starts coming up and telling you you're a genius. STANLEY: We used to talk about it a lot. You know, the word 'genius' is a word that in the '70s really became like... everyone became a fucking genius. Back in the old days the guys that were geniuses were maybe one out of 5,000 musicians. Now it's like if you can play, and play different, and it sounds hard, you're a genius. And Jaco knew that, [judging by] what he thought a genius should be, he was not there. He wasn't close to there. I would hate for someone to say that to me. When I'm 80 and I've played the bass for like 60, 70 years, had written a symphony and had many things acclaimed as being great, then you could call me that [a genius].You should be careful before you use the word 'genius,' because that word is very close to artists. The sad thing is, the person deep down inside wants to be called a genius, and then when someone falsely assigns that title to you, it makes you feel worse. It has a bad effect on you because it's false. With art, it's hard. Music is a very thinly layered thing. You're dealing with sound, and you're dealing with people and their emotions and what they think is good. You can't calculate it. I remember when I started making records as a bass player and I would hear someone copying me, I was fascinated, man. 'Why would someone want to copy that?' It just had to do with the timing, when you come out, what was happening. Now, I can listen to those old records and hey, man, there's guys today that can play rings around that stuff, technically, but when I look back at the time—' 72, '73—what was happening in the time, yeah, it was a hell of a statement. Q: But you need encouragement in order to keep going. STANLEY: Encouragement is the proper thing, if that thing can be said truthfully. I got that from my mother. My father didn't care too much about the music thing. But that in itself drove me more. I just felt that I had to prove something to him. Q: Did you need to prove anything to yourself? STANLEY: Yeah, absolutely. Q: Do you feel that you've done it? STANLEY: On some levels. I mean, when I was younger I never liked the way bass players were looked upon in groups. I got tired of playing in bands where there's a guy—a trumpet player or saxophone player or a guitar player—playing an endless solo out front, and this guy knows the least about music of anyone on stage. So I used to get fired from a lot of gigs. I used to just move the guy off the stage and play the solos myself. There was one band in particular where there was a trumpet player, and the trumpet is a more traditional instrument so he took all the solos. But he couldn't solo them! I taped the song and I said, 'Listen to this, you don't even know what you're doing here. You're not playing the right chord changes, you're messing up the melody. Let me play it.' And he said, 'What, you, a bass player? You're fired.' So I got my own band and musicians that would play with me, and I started writing music. At first that was considered kind of weird, but there was a club that I used to play in Philadelphia. People used to come down and say, "Wow, this is really different," and I just developed a little name for myself as kind of a weird, crazy bass player that was doing some different things. And that's how it all started. |