| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

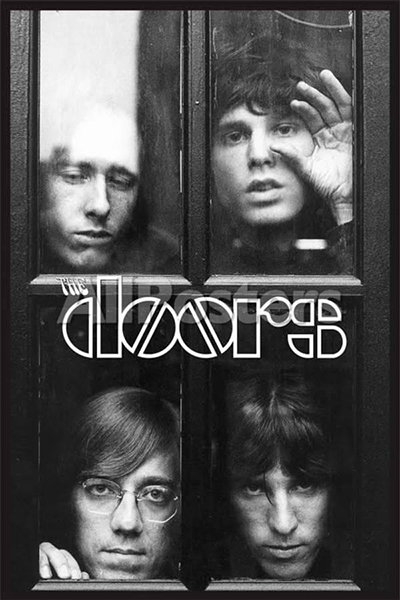

The Doors

Interview by Jeff Goldman

While many other bands would have been content to play the oldies circuit, cashing in on their nostalgic fans, the remaining members of The Doors—keyboardist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robbie Krieger, and the drummer John Densmore—have remained extremely cautious, guarding against any sheer money-making exploitation of their image and their music. In addition, these ex-'60s leaders have kept their creative juices flowing with projects ranging from acting to producing to doing what they do best: playing music. In 1984 I had the opportunity to talk with the three surviving members of the band, and discussed issues relating to The Doors—past, present and future. After Morrison passed away, the three attempted to keep the band together, even recording two early 1970s albums as The Doors, but although many great singers were considered as replacement for Morrison—Iggy Pop, Joe Cocker and Van Morrison among them—the old magic was just not there. As Manzarek says, "It was time to close the door; that period in our collective lives had come to an end. When we would get together there'd be something lacking. Without Jim it wasn't the same." Around 1975, following two post-Morrison Doors' LPs, the band broke up, with Krieger and Densmore going to form The Butts Band, while Manzarek put together his own group, Nite City. After the bands had recorded two albums apiece without much fanfare, the three musicians went back into the studio to work on a new Doors project. Nearly three years in the making, An American Prayer was a labor of love that combined Morrison's poetry, newly recorded music and original excerpts of Doors songs. While not a commercial success, and while just as many critics panned the LP as praised it, the album still means a great deal to John, Ray and Robbie, primarily because, as Densmore points out, "Jim would have loved it." After American Prayer had been completed, the three friends turned their attention to some recordings of classic Doors concerts and sound checks that were thought to have been lost but had recently been discovered. With only one live LP out, an album they were not totally pleased with, the bandmates decided to remaster these tapes. The result was the highly successful Alive She Cried, a well-recorded, insightful album that clearly demonstrates the band's potency. In between the American Prayer and Alive She Cried sessions, the three bandmates had gone their separate ways once again. During this period, Ray Manzarek was the only Door who consistently kept in the rock'n'roll public eye, primarily through his Philip Glass collaboration, Carmina Burana, and his association with the popular and critically-acclaimed LA punk group, X. Carmina Burana, originally written by Carl Orgg in 1935 and first performed in 1937, is a vocal and instrumental cantata based on a series of medieval poems (most likely dating from the 13th century), written in Latin by a group of renegade monks. While this may seem like a rather dry subject for a contemporary album, the stories lying behind these monks are nothing short of wild. "In the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries there was a lot of ergot poisoning," Manzarek relates. "Ergot is corn, rice or wheat smut, a disease that affects the grain. Ergot is also what LSD is derived from. And these monks in these cold, dank monasteries were probably having LSD trips from the bread." Explaining the living conditions of the monks, Manzarek points out that, "Those were rough times, those times were getting close to what we're living in. Although people aren't dying all around us, the threat of annihilation is there. They (the monks] said, 'All around us is death, so what's the point of life?' Well, the point of life is a joyous celebration and dancing with Mr Death, with the Devil, with the Grim Reaper: 'Hey, you're gonna get me, yeah, well until you get me, man, I'm gonna get drunk. I'm gonna sing, dance, make love. I'm gonna have a good time.' And essentially that's Morrison's message. On American Prayer Morrison says, 'I don't know what's gonna happen, but I want to have my kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in flames.'" The other project that has kept Manzarek busy over the past six years is his role as producer of X. Manzarek first saw X at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go, a place where, obviously referring to the early days when The Doors played there, he jokes, "Lots of good things have happened to me." Immediately attracted by X's "hard, raw, energetic sound" and the "off-the-wall" singing of John Doe and Exene, Manzarek just "fell in love with them right then and there." When Manzarek offered to produce their first album, telling them, "You make the music and I'll make sure the sound is right," an unlikely musical match made between a '60s psychedelic dropout and an '80s punk band was born. While working with X, Manzarek began to see similarities between John Doe and Exene's lyrics and the poetry of Morrison. But while he admits that the poets all share an interest in "the dark side, the seamy side of life," Manzarek is quick to point out that "Morrison was more into the mystical side of the darkness, and they're more into the seamy side of LA. We were psychedelic, you know, that cosmic thing, which I think is sorely lacking in today's world." Danny Sugerman, Manzarek's manager and longtime Doors' aid, adds that "Morrison would write, 'The future's uncertain and the end is always near,' and X writes, 'The phone's off the hook but you're not.'" Since the first meeting with X, Manzarek, a former UCLA film student, has not only gone on to produce all four of X's albums but has directed two of the band's videos, The Hungry Wolf and Motel Room, as well. While Manzarek feels that X's recordings constitute "a major body of work," his personal favorite is the debut LP, Los Angeles. He explains: "The first one is always that existential album, like with The Doors, too. Your whole life has been geared towards making that first album, and when you get into the studio and finally put it down for the first time, the energy just explodes. There's so much passion to it." Having been an integral part of two large subculture movements—the hippies of the '60s and the punks of the '80s—Manzarek offers an interesting assessment of the similarities and differences between the two movements: "The punks are rebelling against what is. I think they've taken a different approach to it—they would like to tear it down. I think what was going on in the '60s was that we wanted to make a new world, a new creation. We didn't want to tear down, necessarily, what was there, we weren't that concerned with what was there, we were concerned with the new future, the year 2000, the 21st century." Drummer John Densmore, like Manzarek, has stayed in close touch with the current music scene, performing at local clubs with the likes of Fear's Derf Scratch in a group called The Modifiers, and he also has some reflections on the similarities and differences between the hippies and the punks. He says, "In the early days, what we stood for is just like the punks—you know, earrings and shave your head, shock, confront. Well, long hair was that. They [society at large] thought we were all gay. The '60s did feel like we could change things, and on the surface it didn't happen, but I hope that a few things did seep through. There was a feeling of hope in the '60s, and if you missed that, then it's sort of bleak. But I think that the punk movement is a reaction to the hippie movement, which started out good and then got too drugged out. A lot of people died and a lot of people got into, 'Well, let's smoke a joint and not confront our problems;' and the punk thing is real confrontive." While Densmore has continued to dabble in music, his main creative focus sine 1977, when he enrolled in an acting class, has been performing for the theater. So far his strongest roles have been in Sam Shepard's Tongues and in a play which Densmore wrote for himself, Skins. Densmore admits that he gets "more butterflies acting in front of a dozen people than performing at Madison Square Garden with The Doors." But he also goes on to explain: "There's something I learned from The Doors about sensing where the audience was at. Like, sometimes I'd suggest playing a different song in the middle of a set. I could always sense where it would be good to go. It's like a sixth sense." Along with his theater exploits, Densmore has begun writing a book about The Doors. He is writing it because he feels that there are many things that should be set straight. Densmore explains: "The book is going to be my view of what a lot of it meant. No One Gets Out of Here Alive is fairly factual, but it's not the inside—it's a reporter's kind of view. I'm gonna deglamorize self-destruction. You know, Jim had to go to the bathroom, too! This guy wrote, 'People are strange when you're alone.' This guy walked the ledge of the 9000 building, binge after binge. Well, when did he do all of this writing? He did it the next morning, and that's not in Sugerman's book. All his best vocals were always the day after. In the daytime, when he was straight. So, you can't just drink and wear leather pants." Densmore is also heavily involved with the feature movie on The Doors, which is currently in the works. As with other Doors projects, the three bandmates are trying to hang onto as much control as possible, including directory and script approval. About the movie, Densmore says, "It'll only be a part of the truth, and hopefully my book will fill out another side—just a real good movie capturing several of the mythical turning points that meant something." Like his two counterparts, Robbie Krieger worries a great deal about how The Doors are marketed by record companies and other publicity outfits. He is a little wary about making a Doors movie, primarily because of the mystique surrounding Morrison and the chance that his aura could be ruined if the wrong actor were cast in this difficult role. Krieger has continued to play music through the years—his next album, one in the dance/synth genre—should be out by early summer, and he still keeps up with the current music scene. In fact, Krieger had some interesting observations on MTV and video in general. He said, "It's so limited it's kind of a drag. I'm afraid that kids will get to the point where they won't sit and listen to a record unless they have the video. It's kind of like what TV did for reading." Besides working on the record and movie projects, Krieger is watching his son grow up, and enjoying life after having been a member of one of the most important rock bands ever assembled. Is he happy to have been part of The Doors? "Everybody's dream is to be a rock'n'roll player, and to actually make a living at it is incredible. If you ask anybody in the US if they would like to have been a member of The Doors, what do you think they'd say?" |