| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

by Joy Williams

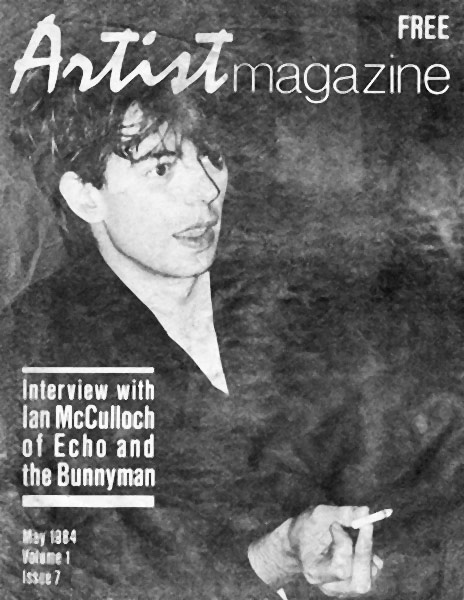

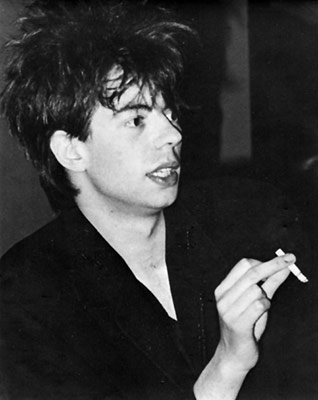

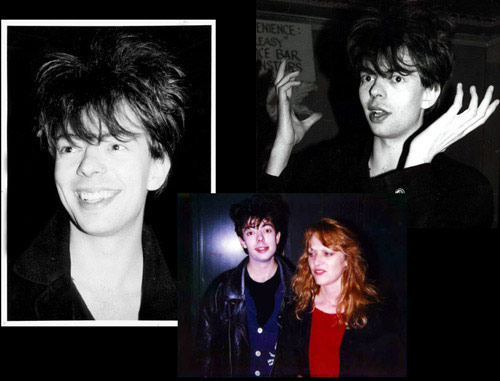

He's quite beautiful, exhibiting a striking personal contrast between the smooth English whiteness of his face and long, graceful hands, and the dark intensity of his eyes and hair. He personifies the romantic poet, more in the line of Byron and Shelley than Chuck Berry or the Sex Pistols. Rock'n'roll these days is a place where many artists go to express themselves. There is the room for individuality, for creativity, for living a life whose sole purpose is the pursuit of artistic goals. Some of the people I've met as an interviewer have been beautiful, sensitive, intelligent people. Ian McCulloch is one of these people. His music is a pure expression of him as a person; it is a true artist's work of art. We'd met at the after party hosted by Warner Bros Records, following the show at The Warfield in San Francisco. We'd talked then, but Warners had told me that there was absolutely no chance of an interview, that Ian had not and would not talk to any American journalist. So I put on my reporter hat and sashayed up to him, announced my name, and said I had wanted an interview, but... We talked for some time that night, until the party was over and management dragged him away. But he promised me we would talk on the record the next day. The band was going to be recording a B-side to a single while still in San Francisco. But Ian had said he felt that I would understand him. And so I was to get the only interview in all of the U.S.

It was almost 10:00 pm when I was told to jump into my car (I was 50 miles away in Sunnyvale) and come to the studio for the interview. It was estimated that Ian would be through laying down the vocal tracks by the time I arrived. When I walked in, everyone was eating pizza. A terribly fatigued Ian and I sat in a break room at the Automatt recording studio that Sunday evening, and we talked for a long time about a lot of things: the music, artistic goals, personality, and well, read on... I had noticed when watching the show the previous night that each person in the band appeared to be an individual, to stand out, and yet there was a seamless unity from the band. "It's no good, each part not being worth anything. If each part is good, then the sum of that is being even better than the whole," Ian explained. "Some bands just don't grasp that. It's about something else, not about writing stuff like U2. It's like the world, I think. If everybody thought like that, then the world would be an OK place." Here is a musician who is said to be cold and arrogant, to not care about people. But the opposite is true; he is drawn to people. "I always prefer pictures with faces on them, than pictures without. A song, to me, is something with a face," he told me. And yet, he experiences himself very intensely as himself. A dichotomy, a conflict, exists. There is a need to express and define himself in the world, a world in which, in a way, he is separate. It is difficult to explain. "It is difficult," he conceded, "and I do feel that I'm different; but I don't always think that I'm necessarily better. It doesn't mean that I live up to my goals any better. It's just that being different is why I'm better, because I know that I fail in exactly the same way as most people—temptation, or the inability to achieve what you want to achieve as a person." So what does Ian want to achieve in life? "Only to be great," he said. "Yes, that's it. There's no other goal, I don't think. You want to be great, and that's what you strive for. That's all that matters. That's why I think we're the only great band, even if we don't always achieve perfection—not that you ever can, but we're closer to that goal than anything else."

Any artist is always trying to stretch themselves further. "It sounds as though your goals are artistic goals," I observed. "Well, those are the only goals that you can 'ave, I think. The minute you start thinking about money and commercial success and all that stuff, then it's all done wrong. That isn't why I wanted to be in a group or why I wanted to sing. Commercial success is OK, but it's after that—people's idea of you because of that commercial success. You get total idiots thinking of you in a way they all think of 'The Next Person in Pop' or whatever. You've just got to stay away from all that and not do things like 3-month tours of America. You've just always got to retain ideas of greatness." Ideas of greatness? You mean like integrity? "Yeah, I suppose," he allows. "Everything's vague when it boils down to it. You can never define what an idea of greatness is but, yeah, words like 'integrity' will do. But that can be misconstrued as much as anything. Groups that haven't got any integrity can sound like they have." He especially objects to the "...'Guitar As Saviour of the Universe' syndrome. "It's all to do with that guitar anthem rubbish... 'Guns to the people.' Guns! Social conscience, to me, isn't saying 'What about the workers,' or 'What about the people on the dole [welfare]?' It's an attitude. We have got integrity and so have U2 and Big Country, but theirs is all about a guitar rather than a person, and everything I do is about people and a person—being me. It has nothing to do with that rallying call that unites people you think have been impoverished or whatever." "Artistic goals. Being true to oneself, one's own vision," I interject. "Which isn't to say that I always believed that everything I've done..." Ian picks up the thread. "A lot of stuff we've done, I haven't been happy with. Not because I haven't tried to remain true to [my ideals], but because... Even with DaVinci, every painting wasn't as good as the other." "I think it's that striving," I note, "that attempt to transcend your limitations..." He finishes my sentence, "And also to go for the highest common denominator rather than the lowest. It's really easy to find the formula; you can predict what is going to happen next, generally, within music—trends and such. That's why Bowie has done so well. I can see the trends changing, and I know that it's easy to capitalize on people. People are stupid in their desire for something new to hang onto." I mention that most people are followers, they like what they think they are supposed to like. "That must be very frustrating at times," a statement-question from me. "Yeah, I suppose," he sighs "Makes you feel good, though, in a way, because at least it means you're superior. Not intellectually, because it doesn't boil down to intellect, it's about personality. I just think there's a lot of character and true personality missing from everything. But as I'm involved in music, from that in particular." What is it that makes some people so different, I wonder. "Don't know," he laughs. "I don't know. That is the difficult thing. But, as I do as I... Well, I do care, but I don't worry about it, and I'd rather be in that position than the opposite one." "Your struggle, then," I venture, "would be to get beyond the surface?" "Yes. Just by being a human being, I suppose, There are not many human beings around, I don't suppose." I'm struggling to crystallize these concepts. "When you say 'human beings,' is that similar to what we were talking about last night, when you said that most people haven't any intelligence? Do you mean awareness of themselves, the world, and their place in the world?" "Yes." He pauses and a big smile lights his face. "Yes. But what's so good about most things like this, is because it is difficult to understand," Ian asserts. "If what we do is ours, then hopefully it's equally indefinable." I tell him that when I write about this band it will be difficult because there is no way I can satisfy people's desire for me to define them in terms of who they sound like. They don't sound like anybody else. "I don't even know where you come from in a contextual way," I admit. "It's just there. The only thing I can figure is that it comes from you as a person." "That's what puts a lot of people off," he acknowledges. "Most of the press like to have the proper chronological thing there. You know, 'The Beatles used Chuck Berry riffs.' We obviously come from a line—we use guitars and stuff—but the reason that we are different from anyone else is because it does come from us. There are other bands, too, that are on their own—like The Fall." I ask him how he first got drawn into music as a means of expressing himself. "Up until I was about 12 years old, I'd have liked to have been a footballer, well, not a footballer, but to have played on the Liverpool Football Team. Then, it was just before I was 13, Bowie came out with [Ziggy] Stardust. I heard it on the radio and I thought, 'Yeah, that's it, a great song.' It was the first song that actually made me shiver. It just had a magic that I never knew existed. And then I saw them on TV. It was more than magic. I mean, I spent a few years just wishing I was him. Well, no, maybe a year..." He looks up at me a bit apologetically, "which when you're 13 is not much of a crime, I don't think. But then I realized it wasn't him that was magical, it was something to do with a certain chemistry between the time and the music he was writing, and his face—the way he looked. It was a magical thing. And I always have that in mind, to create that, to make people shiver rather than make people buy records. I'd just like to do something that is magical and that is just because it is, and not because somebody tells you that it is."

Listening—experiencing, rather—the show the night before, I had found myself transported, swept through a gamut of emotions. "On the previous two nights of the tour [San Diego and Los Angeles], a set had been worked out that I didn't think was right," Ian responded. "It did not hold up. So, late last night, about an hour before we went on, I just rewrote the set slightly and it worked a lot better. We place a lot of importance on what we do live because it involves people a lot more." I struggle to explain my feelings about the show. "The way it started was very powerful. I haven't yet sorted out all my feelings and impressions about it, but the things that struck me were.. it seemed almost religious in a way..." (Ian is smiling.) "You can feel yourself moving inside. There's that transcendent, spiritual thing as well as a tremendous amount of power. Something else that seemed to be running through it was a very deep, almost a primordial emotion. Your voice became an instrument. It's a way of communicating words, of course, but..." "Even when people can actually hear," Ian responds, "most still don't understand what I'm on about—which is OK because it is more than that. Really, it should be beyond that analytical thing, because as soon as you start getting analytical about words or a chord sequence or the note progression or whatever, it defeats that magic. Magic isn't about analysis or even understanding—it's about not understanding. It's not about understanding but about wanting to understand, or wanting to transcend along with that thing. "The concert situation overwhelmed me," I tell him, "and the words receded in importance at that point. I'll go back later and listen to the records over and over..." "Yeah, he agrees. "It's like sometimes with film. You can watch a film and think it's the best film you've ever seen and it's because of everything. One particular thing is very distracting. And then you can watch it again and start to listen to what is actually being said, and the subtlety of the words." I ask Ian just how the Bunnymen came about. He muses, "Just a moment, I'm thinking." There's a long pause, then, "I don't know! Will asked me. Somebody told him I had a good voice. At that time, I did know I had it inside me but it had never come out. Somebody had said something, so he said to me, 'Why don't you come on to my house and we'll mess around on guitars.' And that was it. It wasn't a case of two mates gettin' together; it was a communication thing. It wasn't necessarily an artistic thing, but a [coming] together and projecting of personalities..." "There's a 'chemistry' in the way some people relate to each other," I offer. "For want of a better word," Ian agrees. "But it's like falling in love, you don't get it with everyone." I note that it seems to be present in the band and ask whether it is easy to work with one another. "No," is the answer. "I mean, it does when it does, and sometimes it doesn't. It's like anything. But in the end, I know it's worth the trouble to go beyond it and make things work. There are problems... I get very tired myself, very easily." Tired is not the word for the shape he appeared to be in that night. He was so exhausted I felt guilty sitting there talking to him, knowing that he had yet that night to go back into the studio for the mix. They'd cut "Devils and Angels" in seven hours, working from just an original chord progression when entering the studio. "Oh, that's alright," he'd cheerfully replied to my expression of guilt. He had things he wanted to say, but America is overwhelming. "In England, they've left us alone. The press in England, a lot of them, are appreciative of us. If they think we're sounding worse because we're using too many power chords, it's because they're worried about the way we're going. We're treated a lot more artistically." America presents a problem. "When you live however many miles away, you can't gauge it. I know there are probably some people that will understand, but it's so big. It's like an impossible task—especially when you're not living here." The problem of the artist within society has a long history, but the problem of the artist in rock'n'roll today is horrendous. Artists, typically, are sensitive. They are vulnerable to sensations and pressures that many others hardly feel, and many are torn apart. So they try to protect themselves while they roam across alien cultures, taking their own special vision to the world, to share with those who can understand. They are the magicians of our souls. Interview with Pete DeFreitas |