| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

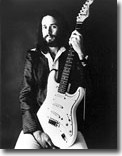

Phil Manzanera Interview by Joy Williams

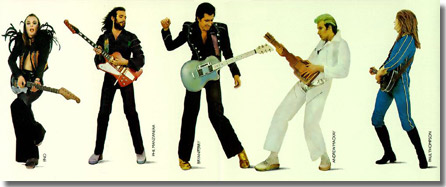

In 1974 alone, he appeared as either guitarist, co-composer or producer on Roxy Music's Country Life, Brian Eno's Here Come The Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), Bryan Ferry's Another Time Another Place and Nico's The End. Further sessions included John Cale's Slow Dazzle before he was drafted back into Roxy Music for Siren. He then produced Split Enz, whom he had discovered in 1974. During the Roxy Music hiatus of 1975, he recorded his first solo work, Diamond Head, as well as working on a reunion album with Quiet Sun, Mainstream. Both works were well received. More work followed, including a major role in the presentation of Stomu Yamash'ta's Go at London's Royal Albert Hall, in conjunction with Steve Winwood. Following the devolution of Roxy Music in 1976, Manzanera formed the eclectic 801 with Bill MacCormick, Simon Phillips, Lloyd Watson, Francis Monkman and Eno. The band was originally in favor of a complete tour but their live performances were whittled down to three shows: a warm-up gig in Norfolk, a guest appearance at the 1976 Reading Festival and a sell-out concert at the Queen Elizabeth hall, London. The latter was recorded for 801 Live. The group then folded, with Manzanera re-uniting with Ferry. One year later, the guitarist issued a new 801 recording, Listen Now!! Its theme was life in a totalitarian society. The work was notable for the use of Godley and Creme 's famous Gizmo gadget, which produced the sound of strings from a guitar. After taking 801 back on the road, Phil issued the less adventurous K Scope. In the wake of Roxy's final split, he teamed up with Andy Mackay in the Explorers before returning to solo work. Phil Manzanera had a rather unusual childhood. His father worked for what is now British World Airways, his job being to set up a new office and then, after the inaugural flight, transfer to a new city to start the process over again. Thus, young Phil found himself in Cuba at the age of 7, after which he spent time in Hawaii and then Venezuela before finally being sent to boarding school back in London, as is common with upper-class British boys. The following conversation, recorded in 1991, ranges freely across Manzanera's reasons for becoming a musician in the first place, and what music and his 20-year career has meant to him. Q: Most rock musicians have come from the so-called working class. There are not a lot of public school guys from your generation who went into rock. Bill Bruford (Yes, King Crimson) told me that he encountered a lot of problems from all sides for taking up such a "lower class" profession.... PHIL: Actually, there are. All of Genesis, except for Phil (Collins). And there's all sorts of strange people, for instance, Joe Strummer went to public school; you'd never think that when you listen to The Clash. And many other punk (musicians) turn out to be these ex-public school boys. It's such a surprise, always, when you find this out. It was a surprise to me. Q: But I think with creative people, all these unusual experiences—moving around a lot, going to upper-class schools—rather than being bad for you, is actually good for you. PHIL: Certainly, travel opens your mind. You're more tolerant. The more you know about different cultures and things, the more you're open. At that time in England, the idea of Latin American music was some very bizarre, sort-of English-type form. It's taken all this time for Europe to discover the raw, exciting South American music. Q: It's taken a long time for South America to discover rock, too. PHIL: It still hasn't, really. But the reason why—and I know because I grew up with it—is that you have all the ingredients you need; you didn't need [rock]. You had something you could dance to. It was a very sexual type of groovy dance music, it was exciting, you had lyrics, it was complicated as well. You didn't need, especially, rock that started in the '60s, which was a bit weak in rhythm—in the early '60s anyway. Q: Yeah, in the earliest rock, at the Sun Records sessions, drummers would still try to play with brushes, like in big bands or jazz, and the bass was very much in the background. The rhythm section was not very prominent. PHIL: Absolutely. But it's that thing of the groove—especially now in Europe—the groove is almost everything, and everything else is just like samples of things around it, bands like EMF.Q: One thing that's always fascinated me about rock is that it was a form of music that started in the U.S. as a cross between black R&B and white country, but which has continuously gone out around the world, picking up new elements, incorporating or fusing them, then returning to America, going out again.... That's what you're doing. Is it conscious with you, or is that just the way your music comes out? PHIL: No, it's done because it's a continuation of what I've always done, what we did in Roxy. It’s that always searching for something interesting and new, and to try to do something different. So you're always trying out different things, whether it's using studio technology, whether it's integrating other types of music into your music and combining it with studio technology. It's a sort of complex mixture of things, which is satisfying and sort of intellectual. Because after you've done 20 years in the music business, and you've done 40 albums....

Q: You ask yourself, "What do I do next?" PHIL: You're right. So, now I just work intuitively and I just do what I fancy doing. It's often wrong, but.... I decided when I was 16 or 17 that I wanted to do this for the whole of my life, I wanted to spread it out, and I wanted to enjoy it. Q: So you decided when you were a teenager that you wanted to be a musician rather than a "rock star," or was it both? PHIL: When (I was) 9 I wanted to be a pop star. Then when I was 16-17, in the middle of the flower power, psychedelic sort of thing, I wanted to be a musician, not a rock star. I wanted to be a musician within that whole sort of movement, if you will. Then, I just didn't care, I just wanted to join any old band. I just wanted to be a professional musician, I just wanted to play. So I didn't care whether it paid or not, it was just the thing of doing it. And so when I got a chance to join Roxy, it was great. We'd go in a van, we'd drive up and down, we'd carry the equipment and whatever. We didn't care, we were just doing it. You have no responsibilities at that age and you can just travel the world. It's difficult to maintain relationships in the music business, very difficult, because you do spend a lot of time either away or in the studio. It's a very time-consuming profession. Q: So how did you actually start playing music? PHIL: My mother started taking guitar lessons in Havana in 1958, so this guitar appeared when I was 7 or 8. She showed me a few chords on it. The first song I learned was "Guantanamera," a Cuban folk song. Then by the time I got to Caracas, Venezuela, there was an English guy there who had an old Hoffler guitar with a pickup on it, and he showed me a couple of R&B licks. Q: And you went through the usual route of playing copies, and....

But essentially what I do is like therapy. Playing guitar and being involved in the music business is the sort of thing that keeps me sane. The power of music is incredible as a form of therapy. And it relieves me physically, too. Things come out, I don't know from where. And when you play a different context, a different combination of things appear. It's very satisfying. I play the same sort of thing all the time, but the context I play in is different, so it appears different sometimes. Q: Playing on stage or being in the studio is like being in another world. All your problems disappear, I'm told. PHIL: That's right. Obviously, the big problem with musicians is that while you're doing that, the other side of things can slip—whether business or relationships. I've decided not to have managers anymore and that's why I also decided to have my own label, to try and get rid of a lot of the things—the bullshit, if you like—out of my life, and have much more control. I just got fed up with being with major companies where decisions were being made which you didn't know about. Where you found out a year later that all the work you were doing was a complete waste of time because they had decided that that was the end of the project. You'd been making an album, but they'd decided before you'd even finished it that they weren't going to do anything for it, they were going to bury it. I just wanted to know straight if something was wrong. If the record comes out and somebody doesn't like it, great. Everybody hates it... OK, fine. That's my fault. But what happens (with major labels] is that you have a series of people who say, "Yeah, it's fine," but in time you find that you're just being strung along. Q: But with your own label you have to pay a lot of attention to the business side of things, don't you? PHIL: Well, I have some people, but at least I control it. So they get on with things. You just find efficient people to do it for you. Q: You've been doing a lot of producing lately. What, for you, is the biggest difference between producing and playing? PHIL: You have to spend a lot more time when you're producing. In some ways, it's a bit boring. Q: Isn't it more consciously intellectual, less instinctive? PHIL: Totally, yeah. Because normally the only way I can come up with good ideas is by actually playing them. Things just happen. When I'm producing, I occasionally have good ideas, but I know that if I was playing, I'd have a lot more ideas. But if I played on it.... It's their album, and I'm trying to bring out the best in what they do, so it would be unfair. Q: There are two kinds of producers, basically: The kind that has a distinctive sound of his own and exercises a great deal of control—Todd Rundgren or Phil Spector for instance—and the producers who concentrate on making a band sound more like itself, if you will. How do you see your role as a producer? PHIL: I think that in producing, it's not an ego trip of a particular guy to put his stamp on. If you believe this particular guy has talent, your job is to create an environment where the artist can feel relaxed, to perform well and do the best they possibly can do. You create the atmosphere. And then there are some technical things. You make sure that you work with a great engineer so that you get a great sound. Then, you have to be very focused. When you're doing a backing track, for instance, you make sure that every bass drum beat is either on time with the rest of the kit, or the fills come out right. So you start with the bass drum and build it up. Or if you want a whole-band sound, you make sure that they all slow down at the same time. Something, so that you get the right feel for the track. So you're focusing on absolute minutia and build it up in stages. And in every stage.... Like, the guitar player might play something and you'll say, "Try playing it another way." And so you're directing what they're doing, while at the same time keeping them all happy so that psychologically everything is going along at the right pace. And you're making sure everything is done at the right time, finishes at the right time, because you've got to keep the record company happy. Q: Are you a perfectionist?

Q: Actually, by putting a little dissonance into things, it can create a more interesting sound, it just has to be the right dissonance. It can make the sound "fatter." PHIL: Exactly. That's right. It does make the sound fatter. And also it gives a sort of flavoring, because something can be too sweet or too much in one direction. I always felt that was my role in Roxy, especially after [Brian] Eno left, was to be sort of more aggressive, to give it a bit more of an edge. I also feel that's my role in producing as well. I always hear the context that the melody line goes in, because I think that is what makes the thing interesting. Because essentially it's very difficult to be original, but the combinations of things creates something different. Q: Yeah, there are only so many combinations of notes possible. That's finite. But when you add all those different little things on a number of tracks, then you get a much greater number of possible sounds from those various combinations. PHIL: Right. It's that unique combination. Again, it's the unique world in each track—and that's what I find most lacking in a lot of dance music, is that there is no world to go into. All the sounds are pretty much the same, stock sounds that come from the technology and are pre-set. Well, you can vary the sounds, but hardly anyone does. And if you do, they don't sound all that different, anyway. So you don't hear a lot of new sounds on records. You hear maybe different rhythms or combinations of rhythms, but you don't go into the unique world. Q: When you're doing a project, rather than being in a band, how do you choose who you're going to play with? PHIL: I just intuitively, whoever's around at the time when I'm.... But funnily enough, most of the same names appear on all the albums. Tim Finn appeared on an album of mine in '77, and this time, I'd had no intention of calling him, but he just happened to show up at the studio and said, "Oh, I've always wanted to do some South American music." Q: Why Latin music now? PHIL: Because I suddenly realized that I've never done anything that related to me personally. Q: That's odd. Because music is an expression of yourself, and most people pull on their own experiences all the time. PHIL: Yes, it is odd. Q: So you can sit back and make a conscious decision as to what you want to do, rather than being entirely dependent on what" intuitively" pops into your head? PHIL: I know the direction I want to go in. But the details of it, the ideas, tend to all be written spontaneously in the studio. You start something going and then it's like one thing leads to another. I can't sit down and write a whole song at one go. A lot of people can. I can't. And that's sort of a tradition of Roxy. With all of the songs in Roxy we'd do all the music first, and then try to think of the top line and see what the music suggests in terms of the lyrics. Once the clue comes, then you create something and then, "Ah, right, now I know how to put the details onto this." What I try to do is make each song create a mood or an atmosphere that you go to that's unique to that song. Q: But each song has to fit together into an overall whole for the album. PHIL: The positioning of them, the sequencing, is incredibly important. It's like a live show. You structure it for a beginning, middle and end. But of course, you know, I learned a lot from the producers we had with Roxy. When you've got a guy like Chris Thomas, who has always been my hero, and he learned from George Marshall working on The Beatles. This tradition passed down from George Marshall to Chris Thomas to me when I was 21, and then of course me working with [Brian] Eno, and it all becomes the way I produce things now. It all boils down to the point of it all. Q: And what is the point? PHIL: Well, the point of it for me is to move people. It's satisfying. It's a mutual trade-off. It's a therapeutic thing. Q: How did you feel the first time you heard a song of yours on the radio? Amazed? PHIL: Yeah. The first time was when "Virginia Fame" was played in England. And it was a total thrill. Now, what's pleasurable is when my own kids hear my songs on the radio. Q: In rock, the audience changes about every 5-7 years. Is it surprising to you that you can keep doing it? After all, many musicians are popular just for a short time and then wind up laying bricks or some such thing. In reality, most people lead "lives of quiet desperation" as the poet said. And then they're dead and gone, as though they never lived. Creating something gives you a shot at immortality. You ever think about that? PHIL: Funny enough, I do now. Probably now more this year, since I turned 40, more than ever before, because you're looking both ways. And also my mother died last year. It was all quite traumatic. But I think if you do something good, people will like it. If you get lucky, a 19- or 20-year-old will come up and say they like it. Well, it is a bit strange. People who weren't even born when stuff came out.... "You weren't even born!" I'll often say that to them. And then you think, well, all the time you put into it, your craft, it was actually worthwhile. And it's nice to leave something as a legacy for your children. |

PHIL: That's right. Trying to learn how to play. One of the ironies is that one of the first things I tried to learn to play was some Creem records. The irony is that about a year ago (November 1991] I was playing with Jack Bruce in Seville, and you know what we were playing? Cream records—"Sunshine Of Your Love" and "White Room" and things like that, on stage.

PHIL: That's right. Trying to learn how to play. One of the ironies is that one of the first things I tried to learn to play was some Creem records. The irony is that about a year ago (November 1991] I was playing with Jack Bruce in Seville, and you know what we were playing? Cream records—"Sunshine Of Your Love" and "White Room" and things like that, on stage. PHIL: No. Brian Ferry is a perfectionist. And I'm sort of the opposite, really. Now, you could call that sloppy, or you could call that intuitive, but I don't necessarily like to make everything perfect. The same thing happens with tuning. I have a different idea as to what is in tune to other people. Something sounds absolutely fine to me and I like it, yet let's say the engineer I work with will say, "Well, that's horrendously out of tune." And I'll say, "Well, I've made a career playing out of tune. So, too bad." I like things that just create an edge. And that's just something to do with, probably, the way I hear things.

PHIL: No. Brian Ferry is a perfectionist. And I'm sort of the opposite, really. Now, you could call that sloppy, or you could call that intuitive, but I don't necessarily like to make everything perfect. The same thing happens with tuning. I have a different idea as to what is in tune to other people. Something sounds absolutely fine to me and I like it, yet let's say the engineer I work with will say, "Well, that's horrendously out of tune." And I'll say, "Well, I've made a career playing out of tune. So, too bad." I like things that just create an edge. And that's just something to do with, probably, the way I hear things.