|

Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

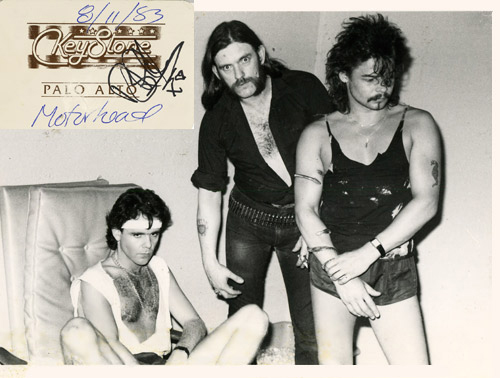

Motörhead interview by Joy Williams

The "leave no one alive" style and sensibility that defines the Motörhead of today first began to take shape in 1975 when bassist and lead screamer Lemmy Kilmister was unceremoniously booted out of Hawkwind. "I was out taking pictures while they was eatin' in the road-house," he told us before their show at the Keystone, Palo Alto, "and my camera was stolen. When I got back, they'd gone without me. So, I hitchhiked across the entire state of Michigan to get to the gig in Detroit. Well, I got there and did the gig, but the next day we rode to Canada and I got busted at the border and locked away in jail. When I finally got out and got to Toronto, I was sacked." When Motörhead was born they were named after the last song Lemmy wrote and recorded with Hawkwind. Featured on guitar and drums were former Pink Faeries stablemates Larry Wallis and Lucas Fox. It was a lineup that for assorted reasons didn't work. They were dubbed "the worst band in the world," and possibly the most positive thing to come out of the lineup was Lemmy's immortal quote, "If this band moved in next door to you, your lawn would die." Eventually, Lemmy split and started Motörhead anew. Philthy Animal Taylor joined more through luck than judgment; he had only been playing drums for two years and got the chance to play with Motörhead when he gave Lemmy a lift to a recording studio. In '76 former Curtis Knight and Zeus guitarist Eddie Clarke was recruited to complete the new lineup. But things were rough. Q: What was your worst period as a band? LEMMY: What kept me going was the desire to prove that the people who'd said we were finished were wrong. Q: But you finally got a manager and a record deal, being signed to Bronze Records in August of '78, and released a classic version of the 1964 Kingsmen standard, "Louie Louie" that dented the lower end of the singles chart. PHIL: We'd tried out several managers in between, to see who'd do the most for us. As it turned out, the guy we stuck with was the original manager. It just seems to be our lot to be always kept on the road. Managers and people like that come up with accounts and they show you bits of paper—I can't make heads or tails of the things they give you, so….

The real turning point for Motörhead came in early 1979 with the release of one of the fiercest hard rock albums in human history, Overkill. The single from that album broke into the British Top 30 and was followed in October 1979 with a massive British tour. 1980 brought the band a Top 10 live album, Ace of Spades, which crashed into the British album charts at Number 4, just days after release. This album was also their first US release. At this stage, Motörhead was still relatively unknown outside the , so 1981 was designated the year to crack the world. A year later, Motörhead became one of the biggest record sellers, storming the charts from Norway to New Zealand. 1981 also saw the release of the legendary No Sleep 'Till Hammersmith LP. Recorded in front of fanatical audiences in Leeds and Newcastle, the album hit the charts at Number 1 just three days after release, and prompted Melody Maker to quote: "No Sleep has set the standard for heavy metal in the Eighties." The majority of 1981 was spent touring Europe and the US and a Top 5 hit was recorded with Girlschool, The Saint Valentine's Day Massacre EP. All of this resulted in Motörhead winning virtually every category in the Sounds 1982 readers' poll, a feat they went on to repeat in more than twenty foreign magazines' readers polls. But in 1982 there also were problems. Tension built up in the band, resulting in the sudden exit of guitarist Eddie Clarke. Former Thin Lizzy and Wild Horses guitarist Brian "Robbo" Robertson was flown in at 24 hours' notice as a temporary replacement to complete the American dates. Things worked out so well that he soon became a full-fledged Motörhead. Q: So, 1983 brings a revitalized band to our shores, meaner and harder than ever. But what do you think helps the band more, records or touring? LEMMY: They help each other. ROBBO: The radio's not going to help us any until we've been on the road. LEMMY: The radio in this country ain't gonna do nothin' for us…. ROBBO: We don't get radio play anywhere. There are no radio stations over there (England] except the local commercial ones. LEMMY: It's all silly shit. Q: But you're not going to change your sound, regardless? LEMMY: Well, it's changed a little now that Brian's joined the band; I think it's gotten more musical. Q: Still, you have this image… You seem to be one of those bands that attracts a weird element. PHIL: We get the odd maniac. On the surface they're like dedicated fans, they worship you and follow you about and all that. It seems strange to me. I mean, I can understand a kid being a fan of a band, but to be actually, fanatically devoted…. It seems very weird to me, the fact that they've got nothing else in their life at all apart from, in our case, Motörhead. LEMMY: He's thinking about the guy we met just recently. A real weirdo, he really looked like Charles Manson! [Lemmy does an amazing imitation of Manson for me—downright scary!] It's people like that that shot John Lennon. We appeal to the guys who stand in front of their mirrors with their guitars. Q: Phil, you have a rather amazing set of drums, I've never seen anything quite like it—and the audience can't even see you behind it. PHIL: It's not really that big, it just looks it because it's all chrome. The roto-toms are up high because I have no other place to put them, and I sit very low behind the kick. I'm not a tall person anyway, so even before I had the roto-toms, unless you were in the balcony nobody could see me. Every now and then I try to remember to stand up, but I'd rather have the roto-toms and get the sound I want than actually be seen—I mean, people know I'm there. Q: Besides, you're competing against Brian's guitar, and you've got Lemmy playing bass, and there are the sheer decibels….

PHIL: And also the sound is not exactly as clear as a lot of other bands because of the way Lemmy plays bass. He plays it like a rhythm guitar and he also likes a very trebly sort of "clappy" sort of sound. The most bassy, bottomy sounds you hear are the tom-toms and the kick drums because Lemmy's sound is more really like a horrible sort of screeching, scratchy rhythm guitar with lots of bass on it, rather than like a bass guitar. Q: So he doesn't play off you, and you're left carrying the rhythm section. PHIL: Well, once Lemmy starts playing, he's sort of out there on his own, in a way. It's something that came naturally; but when Robbo joined the band, we started working it out a bit more. When Eddie was with the band I played more with the guitar than I did with Lemmy, because he's not really a bass player. Lemmy always plays so fast that it's always been down to the guitarist and me to keep the rhythm and melody going. Lemmy is just non-stop playing all the time, so for the highs and lows of the numbers, the ups and downs, light and shade—whatever you want to call it—it's basically down to Robbo and myself. I'd never played much before, so it's probably a lot more difficult for Robbo than for me. He'd always played in bands that had a proper bass player, so to speak. Q: So, Robbo, do you enjoy the change, the challenge? ROBBO: No. One of my most treasured possessions is the four boxes of Glenn Miller 78s that my father gave me when I left home at 17. And I've been working on synthesized music with Warren Cann from Ultravox. It took over a year and a half to record and mix it; it was done on a 62-track—we slaved 3 decks—that's why it took so long to mix it. I've always been involved in mixing. I mean, I can sit at a desk and engineer, if I want. Q: So you like to do a lot of different things? ROBBO: I always do that, always. People say, "What are you doing, joining Motörhead?" I didn't say I like them. I hate Motörhead. But I respect them for playing shit for so many years and making money at it. And they're original. I won't say Lemmy's a very good bass player, but he's very original. Lemmy is Lemmy. And I know my style is very forceful and always has been. The minute I left Thin Lizzy, they went straight downhill. Not so much because I left them, but because they didn't spend the time trying to get someone in the same vein to replace me. Very rarely have I had to ask, "What do you want from me?" The music tends to change my approach because I'm classically trained and I can change my approach from heavy rock to slow to… Well, I played with the Average White Band. So there you have it—just three guys trying to make a living in rock'n'roll, doing what they can and what they have to to survive. It's not an easy life, even for those who have tasted success, as these three have. Lemmy's been at it since 1962, Robbo since he was in his early teens. "I've been on the road for the past six years," he sighs. But it's not all grind and groan. "It's fun playing, you live for the show at night," any performing musician will tell you. And for now, the sound check is over, you've been fed, the interview is done, and you can have a couple of drinks, a little chat with those about backstage, until the road manager comes in and says, "Everyone, out—you, too, Zoë. And you, Robbo, get dressed! You've got 5 minutes to get on that stage." |