| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

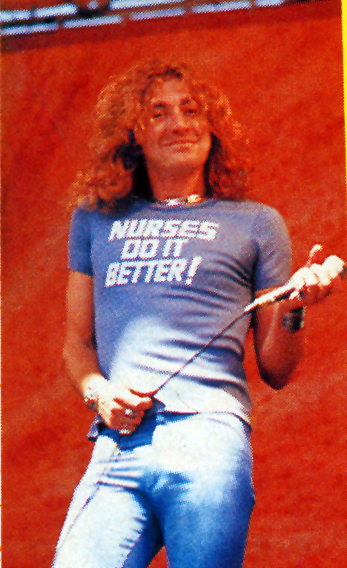

Robert Plant interview by Joy Williams

For many years after the demise of the wonderful—and wonderfully successful—Led Zeppelin, Robert Plant seemed to flounder. Certainly, solo success eluded him and it seemed that both fans and critics had written him off as a has-been. In the meantime, Plant was struggling with his own demons. The years of superstardom in Led Zeppelin, and the excesses that had allowed, had led him into a psychological corner. From a public phone booth in front of a fish-and-tackle store on an island off the coast of South Carolina while on vacation, Robert Plant told me that he had paid a heavy price for coming to think he could do anything he wanted "because I was a rock'n'roll superstar." "I looked up one day," he suddenly said in the midst of our talk, "and I found myself all alone, staring at the walls in a little room. I had no family. I had no band...." Surprised, I stuttered, "What happened? It all just fell apart?" "No, it didn't fall apart," he answered softly. "Everybody left me. Nobody wanted to be around me anymore." It was a terribly painful time, and the only way he could see to heal himself artistically was to reject Led Zeppelin and to strike out entirely on his own, to find out just who he was outside of that band. Or, as Robert himself put it, "Zeppelin was a very satisfying musical thing for me for many years. It was a very serious thing. I loved it, you know. And to start on my own, I had to delight in my ego state. I wanted to be seen standing on my own for better or worse, even if I never again had any more commercial acceptance. So when I started out I sort of had to deny the whole [Led Zeppelin] thing. It was a chore. 'Don't mention it, otherwise I'll walk out of the room.' Besides, you can't do the same thing over and over and over again and say that it's free expression, that you are artistically expressing yourself. You can't just do it because it's safe." Q: And is that why you were against doing a Led Zeppelin reunion tour?

ROBERT: Yes. Sure is. It was a great band. You can't actually get it together, like Deep Purple or something, and take it out there. It's incredibly old. It's like doing the goosestep. Out of fashion. I don't think it's a good idea. But the whole thing was off the wall. It was crazy. One of those one-in-a-million combinations. Q: Led Zeppelin's mythology is pagan and is out of old England.... ROBERT: It's out of anywhere you like. There's no specific spot. However, Valentine's Day is pagan. They make a lot of money out of that. What we were doing, there was no encouragement in any of the lyrics. There was no abstraction that would encourage negativism. What someone does in their own room behind closed doors is their own business. A guy from room service tells the Baltimore Herald newspaper that he was hanging upside down like a bat, then he might have even exaggerated, eh? But, I mean, the whole Led Zeppelin idea is old, it's ancient. Q: Do you have a favorite Led Zeppelin album right now? ROBERT: No. I feel that my newest album is always more important than whatever was. Q: Do you have a favorite solo album? ROBERT: Now And Zen. It's a great emancipator. Because I feel I've stopped worrying about all the similarities and started enjoying the parodies. It doesn't sound tired. Q: How did the Robert Plant Band come together? ROBERT: My management got it. They fished around to see what they could come up with. All these tapes came in through the letter box every morning. And then suddenly from Virgin Music came a demo tape which was excellently performed by a group called The Rest Is History. And that was done by Phil Johnstone, he was part of the band. And then he brought along Chris Blackwell the drummer, and he, Doug Boyle the guitarist and then Phil Scragg the bass player (later replaced by Charlie Jones). Q: So these are the members of The Robert Plant Band… These guys are very young, early 20's. What's that like for you? ROBERT: Working with these young guys is such a choice experience because they had never played outside of bars before. And they have the honesty and enthusiasm. Q: But then you asked Jimmy Page to play on Now And Zen.

ROBERT: I just wanted some of that stagger. And, really, I just wanted my old partner around then. I wanted to see him hanging around with his head dangling on the floor. He was only in the control room of the studio playing and everybody is saying, "God, can that man play!" Q: What made you finally change your mind about denying your Led Zeppelin heritage and begin to include Zeppelin songs on the Now And Zen tour? ROBERT: I've had many things in my life which are far, far removed from this ego exercise that I'm going through right now, so I have to take it on the nose. I am the pilot of the storm. I was the pilot of the storm way back when I first said "I am the pilot of the storm." That doesn't change. And the pilot doesn't get any more tired, he just gets more confused sometimes. I was playing a charity show and at the sound check another guitarist was telling me what a breath of fresh air it was going to be playing with one of the Old Masters. I asked him how he came about the conclusion that I was an Old Master, and he said he'd just spent a year with Rod Stewart and I must be an Old Master, too. And I said I'm not an Old Master. At the sound check, what he did was really good. I mean, we just played some Beatles stuff and his approach to playing was very much like Page's. Immediately, when he threw the guitar around his neck I noticed that it was quite low down there. It was right down there by his groin, and in order to play he had to contort himself into some kind of Zen-like position to barely make it work. And I looked at him and he looked at me, and I realized I was looking at.... It was as if Page had sent himself in a different form. It was on the tape and it was the only thing that made sense for me for about six months, coming from somebody else that I hadn't got anything to do with. In working with other lyricists, because we talked about Zeppelin, I found I had to explain things. And the more we talked about the current Zeppelin approach, the more it washed off on us, because all they needed to know were a few little points of reference on the map and they tuned into it and we were off. "Heaven Knows," it was a real great start for somebody to say, "You can have that song." It was great because to me... because the version I heard had a thing in it. It sounded very dramatic, as if it was cut in the "River Deep Mountain High" style. Had Page and I continued to work together and everything worked out, it would have been nice to think that we would have got to this point. That would have been quite a logical point, in my book, to have gotten to. I think, if I have been stubborn, it's not been fair to people who come to concerts. It's nice to have a little extravaganza now and again, as long as it's not "Stairway to Heaven." After "Stairway to Heaven" I never got over looking at those lyrics. If I went out to look for a job, I'd have to take those lyrics with me and say, "Here, this is what I do." It wasn't always appropriate and that wasn't always where I was coming from. It's all fuel to the frustration of wishing to be a star—of, like, wanting to be relative to the '90s, and not some relic from 1978. I was on my way to love at that time. Always. Whatever road I took, the car was heading for one of the greatest sexual encounters I'd ever had. I never thought that I would go through so many things in my life that I would never sing that song again. I was astounded that I'd fallen into the idea so easily of playing with Jimmy and Jonesy again, albeit mechanically, not in the name Led Zeppelin. I was letting myself down, my own individuality, my own persona and everything I'd worked for. I was sticking a knife in its side. It's kind of Robert Plant. And Robert Plant was being superseded by the return of the monster. I could see that it was making a lot of people happy. A lot happier than they were the night before when I played in Detroit with the new band. And the cackling cries of "Where's Jimmy?" continued wherever I played next. Media-wise, the band became far more of a backing than they really were. So, that was a hard one to get over for them. But with this band and this music, basically I wanted to get across to college kids, because my music.... I think about it a lot, I work hard on it and I don't want it to get just wishy-washed around with all the formula music. 'Cause I wanted to get to the kids that wondered what happened to the guy who was the king of fucking rock in 1971. Q: You're projecting your old program? ROBERT: No, not at all. There are many people out there who spend their time learning and thinking. As a consequence, when they come to music they've got to be pretty intense or emotional about it. It's got to be a relief for quite hard work. And what it all means is, things are aligning themselves from centuries ago. It's kind of fun. Now And Zen is like that. It's a little bit mystical. It's Kashmir. Not to be taken too seriously, but to be played three times a day. I would like to be involved in some of the larger music scenes, like Green Peace. I would like to play festivals. And its that kind of competitive thing I'd like to do. I don't need a Ferrari. It must come across that I am serious. When I first put this band together, we did some gigs around England. Just seeing what we wanted to do and what we didn't want to do anymore. We called ourselves the Band of Joy. It's fun to do that. I wouldn't mind calling the whole thing that. Life's too short. And it was great stuff and I didn't realize I'd been playing it since I was 12. And all I know is, it's time I cut that record. Because I've been singing it when I've been drunk so many times, staggering down the street, "Life's too short, and you're too sweet." And if we have a hit, I would really like to play to the intellectuals. Because in 1975 I really didn't have that honor or privilege. |