| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

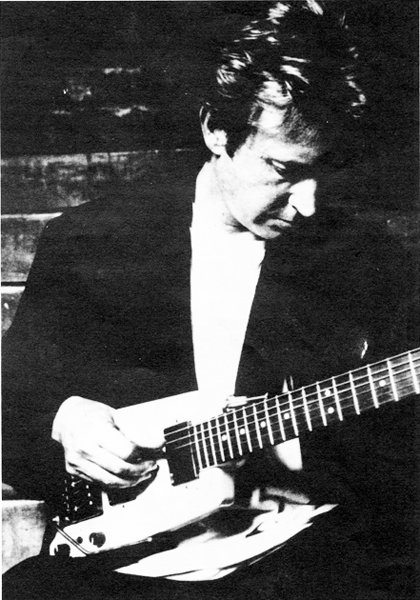

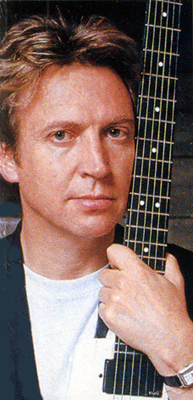

Andy Summers interview by Joy Williams

The band's canny, forward looking combination of pop hooks, exotic rhythms, blond good looks, adventurous management and good timing won them a mass following around the world. Their distinctive sound and songs centered on Sting's bass riffs and vocals, with Andy Summers' atmospheric guitar and Copeland's intricate drumming as a backdrop, quickly became the most influential approach since punk. Copeland formed The Police with Sting and guitarist Henri Padovani in 1977, replacing Padovani with Summers after some months of London club dates. Summers had played with numerous groups since the mid-'60s, including Eric Burdon and the Animals, the Kevin Ayers Band, the Zoot Money Big Roll Band and the Neil Sedaka Band; he had also studied classical guitar in California.

From the start, The Police distinguished themselves for their maverick business practices, including a tour of America before they had released any records in the country. With this approach, they had a following ready for their first American release, "Roxanne," which went to #32 in America in 1979 (it was already a British hit). From that point on, The Police joined the world's superstar ranks, but there was always a great deal of tension inside the band. During the early '80s, rumors were great over purported ego clashes, although pressure was relieved somewhat by all three members participating in outside projects. Then came the rumors of a breakup. Officially, they were denied for a year before finally being confirmed. Why? Because the business structure stood to make more money if the public believed the band was still together than if they believed they'd broken up. Such is the music business in America. When I first met Andy Summers, he was quite delightful, except when I mentioned Miles Copeland's name. Miles, Stewart's brother and manager of The Police, has a reputation inside the business as a very unpleasant man, and this Andy vehemently confirmed. After the Police, Andy had at first intended to play in a new group with Stewart Copeland and Stanley Clarke (the great jazz fusion bassist). But that fell through because, Andy said, he just couldn't stand one more minute of "that vile man," and walked out one day. The night we met, he was playing in Berkeley, just across the bridge from San Francisco. I never did do the interview that night, there was just too much going on, so we decided to meet another day at his studio in Venice Beach, part of the Los Angeles area, and the district next door to his home in Malibu, where he lives with his wife, daughter Layla and the twins. He was still sick with a cold, and I was just coming down with one. We sat around rather listlessly and talked over lunch. But in spite of his obvious fatigue, Andy had no problem discussing the nature of music and what that means to an artist whose particular muse this is. Q: Most of your work since leaving The Police, whether with Brian Eno or solo, has been instrumental, and I suppose that your next record will be, too. Is it safe to assume, then, that you like jazzy instrumental music better than rock? ANDY: I think so, yeah. I think it's more my natural genre. I'm not that interested in songwriting. I mean, I like working with singers, but I think where I'm at my best is writing instrumental music. Q: Some people like lyrics, some like melody, some like sounds… ANDY: Not many people write words that are worth listening to in rock music. They're garbage, most lyrics. I'm more interested in creating beautiful lines. Especially right now, I'm going through a whole process with the guitar where I'm working with a lot of loops, and I can really do it well in the studio where I can create three or four digital loops and have them all running against each other. And they create beautiful textures. That's one thing I do, but there's not so much melody involved in that in an obvious way, like a line. And the other thing I'm doing is working with lines, a structured line as a melody. So, those are two distinct areas I'm working in. Q: You don't really think of yourself as working within a genre of music, though, such as jazz or new age, do you?

ANDY: Obviously, I've listened to and been influenced by all of those different things. But I find it hard to actually fall within one bag and do that. Some musicians obviously do, they play jazz in the "jazz style," whatever that is, but I find that too limiting. All the styles seem too limiting if you're trying to individuate and kind of be yourself and really express yourself through music. I think it's very natural now, when music has crossed into so many areas, one into another. It's not like the '40s, where you really did play be bop jazz or popular lightweight music. Rock'n'roll has kind of opened all those doors up and let everything blend into one another, so I think at this point it's very acceptable to go beyond those definitions that are convenient to people who have to slip a record into a certain rack. Q: One thing I struggle with is trying to describe music in words... ANDY: Any music worth anything is sort of beyond words. You can't describe it in words. Words become useless. They're not up to the power of the thing they're trying to describe. You can only experience it. Q: As an artist, though, what you are doing is exploring. ANDY: Exactly. You have a duty to keep pushing the boundaries, to find new ways, fresh ways, for things to be expressed. Q: A duty? ANDY: I think so, in a way. Otherwise, you might as well be manufacturing soap. If you've got one good bar of soap, then you just go on making that for the rest of your life. I think music and art should be beyond that. They're supposed to be of a higher nature. Probably a lot of people go about playing music in the same way, but there is a level of talent.... It's how good you are, really, and what your taste is and what you want to hear. You know, someone could use that process and still come out with a very sentimental melody. Q: Do you consciously strive for, oh, beauty? ANDY: Definitely. Maybe I'm a born optimist, but I can't.... I try, in a sense.... What I don't like is sentimentality. I don't like cheerful music. Q: I suppose that if you have to live, you may as well be happy—that's not the right word, but.... ANDY: Well, you have to develop a sense of irony. I guess, in a way I'm trying to get music that's centering, because that's the best place where you write from. I know that I can come in the studio and I'll be not centered, sort of distorted and full of (problems) of the day, but after I'm in there for like three or four hours, I suddenly find myself. I'm in there playing and playing and then after a while-it takes a few hours—I find I sort of slip into a different mode. And that's when it starts to work. I've become more and more conscious of how important that feeling is. And when you do get into that more centered state, you really do much better work.

Q: It's a feeling that this everyday world is not really there; it's been replaced by something else. I call it "creative land" because that's when things start to happen. It's like things come together, they appear in your head—it's really an altered state of consciousness, I think. ANDY: Yeah, yeah. You have to realize it is there. You don't get it every day, but you can learn how to recognize it. Q: And when I'm there, I find it very difficult to do things in a very linear and logical way. For instance, I could program computers very well if I was allowed to play with it until the solution "appeared" to me, just like when I hear music or see movies in my head. But if was made to write it out all logically first, I couldn't do it. ANDY: Maybe that's why computers drive me around the bend, too. I have to have someone do that side of things. It's a more left brain type of operation in a way, I guess, and I don't think that way at all. Q: You do use a lot of electronics and software and effects, however. ANDY: Yeah, you know, I am a musician who is surrounded by both hardware and software to a large degree. But, actually, the way I operate is more or less a two man operation now. I may have all this equipment, and I play my instruments through it, and I have enough of an understanding to be able to direct somebody to what I want to get out of it. But I try not to become totally engrossed in it. I don't find a need to, and I'm not that good at it. So I have someone who is always with me to do that. I like to keep my energy more for the actual playing and composition of music. I understand things as I go along, and I keep an eye on what's happening out there because, technologically speaking, things change week by week. If there are better things happening.... It's like equipment has become a hole into which you pour your money. Q: Some people, especially so called "serious" musicians, have a tendency to say that anything that's been invented in the last several years isn't "real." Your strings should be cat gut, you should play only acoustic instruments; they're against effects, synthesizers, electronics.... But you use a lot of those things. ANDY: I use a lot, and I get the most beautiful sounds out of it now, too. And a lot of them are very inspiring. I mean, they're much more subtle and real than they used to be ten years ago, even five years ago. They're really at an advanced stage now. The main thing I have is a large effects rack that mostly has about 15 different modules, which I play my guitar through-harmonizers, digital echoes, choruses.... I can get all these very beautiful sounds with them, especially the harmonizers. My guitar signal goes through all that, and it's changed however I want it to be because I have it organized through a computer which is under my foot. I can combine the sounds in any way I want, and it's more or less infinite what I can do. It's very complex and a lot of it I don't understand, but there are enough guys around who do. It's become very specialized. I find that I have to have somebody with me all the time. I have this 24-track studio and I have a lot of equipment; it's just too much for me to take on alone. You know, I have a family, I have to play. I keep my head on the music and I keep practicing the guitar or playing. I think a lot of musicians lose it slightly because they get so involved with equipment, with being one step ahead with the equipment, they forget about how do you construct a more sophisticated melody. A lot of the time the music is not advancing, the equipment is. Q: But the equipment should be a slave to the music. ANDY: Of course it is. It's all merely a means to an end. It's a tool. I mean, a good tool is worth checking out, but don't lose sight of what it is. You can use it for a while, and then after a while it may pall--you know, things get better. You can hear it too much, that sort of digital echo or something. We're way beyond a fuzz box here, we have extremely sophisticated harmonizers and digital echoes that just sound very beautiful. Q: It's amazing how quickly things have changed. You can look back just a few years and think, "Then, I thought that was just so earth shattering, but now...." ANDY: Yeah. Well, we've lived through it. I mean, it's the first time in history. I started off with a fuzz box, like everybody else. Now, it's incredible. Q: Do you respond to a certain sound, do you find that a sound in itself will move you? ANDY: Yes. I have certain echoes, for instance, that I just love. I have a thing on a machine called a dB5, which is the infinite reverb, which is a beautiful shimmering echo that just goes on and on with kind of a twinkly sound to it. It's really beautiful. Very lonely sounding. Q: Outer space again. ANDY: Yeah, or inner space again. Q: As for composing.... ANDY: I can start in a number of ways. There's not just one single approach. I mean, I have a number of different approaches which I could speak about. For instance, I might have a really formal idea. Like, I'm going to write something in a certain mode and there is a set of chords that will work with that, and I'm going to take this mode and somehow construct a pieta, a really formal idea, which means you could come up with a really crappy song. But you know I could take that as a starting place and say, "Well, I want to do something based on an arpeggio in 7/8 time." You know, take formal approaches and then sort of start trying to carve something out of the air. Or, I could put up, for instance, a drum machine and just find a good groove and just start to play (the guitar). I've done that, I've done all of that on this record, in terms of working up stuff. And I've jammed for 15 or 20 minutes, got into different grooves, and I'll listen back to it and see if there's anything there that was a good starting point for something. Or I'll just improvise on the guitar. Or work out a set of chords and put those down on tape and start trying to put melodies against them. Q: Do you ever feel isolated within yourself, that you might want some more outside input? ANDY: No, I don't actually have a problem with that. No, at the moment I'm enjoying it. When I start the formal recording of all this I'll have another guy come in—this guy David Henshaw, who works with me—he's a very good writer and composer on his own. This time I've written everything already, but there will be somebody to sort of bounce ideas off. Which is good; yeah, I do like it. But I've collaborated—on songwriting particularly—with other people, and I do enjoy it, yeah. More so in songwriting than instrumental (music). I'm doing (work) now that I should've been doing before, really. For the fist time I'm doing my own (music). It's never been heard before, what I'm doing—from me. Q: Does that mean anything special to you? ANDY: Yes! It's a step in the right direction. Finally, I'm really getting on the right track. I'm doing what I should've been doing before, but for one reason or another, I hadn't gotten to it. Being an artist, I realize this is the process of individuation. To me, that's the path through life, discovering myself through that—more than anything else I've ever been involved with. Q: And yet you also try to reach other people. ANDY: I believe, as corny as it may be, that music actually has the power to change people and move people and can actually improve their lives. The best thing I feel I can do is make the best music I can. I think that's what I was born to do, and I think that's the most I can really do with my life. So, that's what I intend to do. Finally, I'm getting on with it. People may find that bizarre, for someone who was in a group like The Police, to actually say that. In a sense, it was great being in The Police, but I think it delayed me for a while. Q: I don't want to do anything that other people do or have already done.… ANDY: It's just not interesting, is it? You want to have some surprises, and let nature do something and surprise you. Playing music, the best time is the accidents. We used to do that in The Police. That which just happens by accident is nearly always the best, and that's what should be kept in. I'm interested in playing music that really stands on its own and isn't interested in pleasing people, but at the same time is accessible and excites people because of what it is. It's a hard trick to pull off, a very hard trick. Q: But you seem to feel pretty good about your own progress as an artist. ANDY: I do, yeah. It was a little difficult after The Police. I got sort of sidetracked, I did a couple of movie scores. There was a period where I was sort of drifting back and forth between L.A. and London, when I was sort of all over the place. I didn't settle down for a while. I did a couple of film scores, then I spent six months making XYZ, which took a long time. Then I went off on holiday. I had to reorient (myself]Q: Music is such a personal thing that now I can watch a concert and pretty much know what that artist is like as a person. ANDY: Well, I think music is absolutely a reflection. No matter which way you try and contrive it, it's going to reflect you somehow. You can't cheat it. People have to survive, they have to live, and if they play an instrument, sometimes they have to do what they don't want to do. And very few people are strong enough to withstand (that pressure); it's hard. Q: And there's the need for approval. It's difficult to go through the initial stages, where nobody understands what you're doing and doesn't accept it. ANDY: Well, you believe in what you're doing. You have to. Q: That's almost mystical, though. ANDY: It is, a little bit. And I'm sure it's the one reason I actually survived the years I've been out touring and all the rest of that. It was only actually the music that really kept me going, the fact that I could actually play the guitar at the end of the day, I could actually play the guitar through all the personal problems, the shit that you have to go through. But that's what art can do, it can heal, and it can help (people) to be aware of things and be touched in a way that maybe they wouldn't be in their everyday life. As an artist, if you have a duty, it is to try and make art that does that to people. I believe that. |