| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

Primal Colours

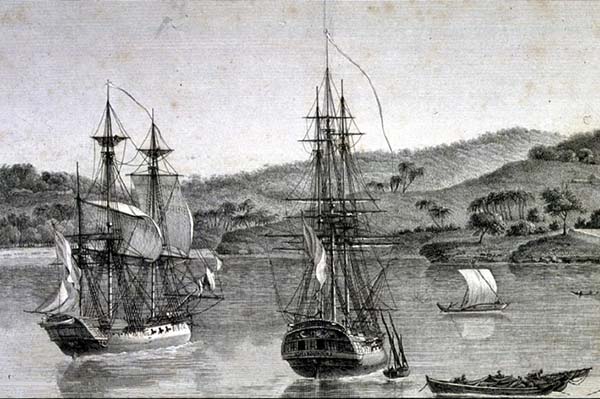

On October 18, 1800, Captain Baudin set out from Le Havre with two corvettes, the Géographe and the Naturaliste, 22 scientists, five zoologists, three artists and two astronomers, among others. What began with grand instructions from Napoleon to survey New Holland (Australia), Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) and southern New Guinea descended into a tragedy of scurvy, 40 deaths and desertions, and missed moments. "If we had not been kept so long picking up shells and catching butterflies in Van Diemen's Land, you would not have discovered the South Coast before us," one of Baudin's officers later told explorer Matthew Flinders. In March 1804, the Géographe crawled back to Le Havre with a living cargo of 72 animals and birds, but no captain (Baudin died of tuberculosis in Mauritius). For the French, it was an embarrassment soon forgotten. "The French could look back on their marvellous victories upon land," says maritime historian Frank Horner, "but the less said about their maritime performance the better." Baudin's name was deliberately omitted from the official account of the voyage, written by an enemy. "As Jules Vernes said, it was as though there was a conspiracy to say nothing about him," says Horner, author of The French Reconnaisance: Baudin in Australia 1801-1803. But as Terre Napoléon makes compellingly clear, Baudin did leave an artistic legacy. After the expedition's official artists decamped en route, it was his decision to replace them with assistant gunners Petit and Lesueur. "It will be seen from the work of these two young men whether my choice was good or bad," wrote Baudin in his log. The results were stunning—both as historical documents and as art. Lesueur, who had providently packed "ma boite de couleurs, crayons, etc," was among the earliest colonial artists to record an Aboriginal corroboree, while Petit's portraits of Tasmanians were the first to name and humanise, rather than caricature, their indigenous subjects. "They don't have the anthropological gaze," notes Hung. "There's incredible empathy."Lesueur's images of Australian flora and fauna are similarly lit by strong emotion. An almost surrealistic spirit invests his flying possums and kangaroos, while his sea creatures are flushed with phosphorescence. Often using his weekly alcohol ration to preserve his specimens, and deploying a fine camel-hair brush in often wild seas, Lesueur worked upon vellum images of gossamer delicacy. Such exquisite beauty helped veil a darker purpose. For the French emperor, the expedition's quest for scientific knowledge was indistinguishable from imperialism. "The true power of the French Republic," Napoleon had declared, "Must henceforth consist in not allowing there to be new ideas which do not belong to it." And while the Naturaliste's Françoise Peron was busy collecting specimens during a five-month sojourn in Sydney, the senior zoologist was also casting his left eye (he had been blinded in the other while in the revolutionary army) about Port Jackson, dreaming of a French invasion he would later plan out in his memoir. Viewed in this light, his protégé Lesueur's topographical drawings of Sydney Harbour brim with a covetous lasciviousness. Nearly 200 years later, the secret visions of Petit and Lesueur are amplifying the picture of Australia's colonial past. "It enables us to think differently about what might have been," says Paul Carter, the exhibition's historical advisor and author of The Road to Botany Bay, "and also to think about how the foundations of this country have been part of a much larger process of late 18th century European expansion. It's not just a crude question of, What if we'd been French? It's a part of the forgotten way of seeing this country." |