| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

|

Woodstock interview with Muruga Booker by William C Leikam

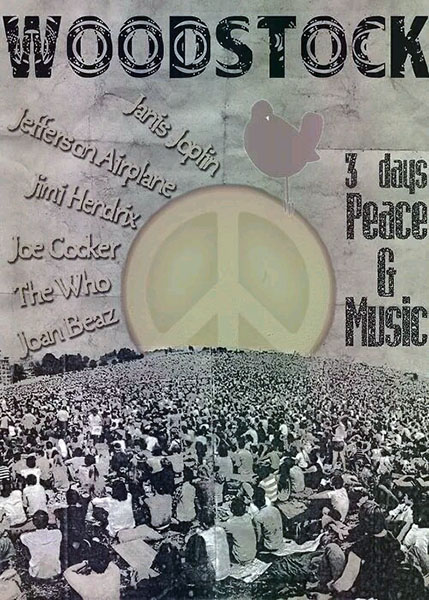

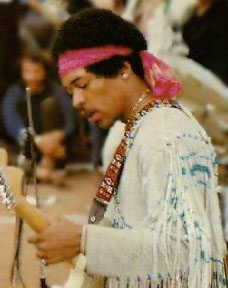

It was the time of flower power, free love and of course, rampant and open drug use, when entering a drug treatment center was the farthest thing from their minds. It was well known that the group Iron Butterfly laid down a path of fights and violence in the wake of their concerts and, although they were invited to play at Woodstock, events turned so that they didn't appear. According to Lang, in his book Woodstock Festival Remembered (1979): "When they called… from the airport and said they weren't coming because we hadn't sent the helicopter, it was the best news I had heard in weeks." A few of the big names—The Who, Creedence Clearwater, Carlos Santana, and Jimi Hendrix—gathered the press when it came to Woodstock. The rest are legendary: The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Arlo Guthrie—you know them. But what was it like for Steve Booker, Tim Hardin's drummer, to play the biggest little festival in the history of rock music? As a direct result of Woodstock, he is today known as "Muruga," the name given to him by the Swami Satchidananda. This is how Steve "Muruga" Booker remembers Woodstock. Q: When and where did you meet Tim Hardin? How did you get to Woodstock? MURUGA: That's a good one, but it involves the whole scene of the late Sixties in New York. I first met Tim in the Café a Go Go in (Greenwich) Village in New York. I was playing with Jim and Jean at the time, and we were promoting a couple of albums. We were all hanging around with folk artists like Phil Ochs and Harvey Brooks—who also played with Bob Dylan and the Electric Flag. Jimi Hendrix was often the guitar player in these "jammin' bands" and I was the drummer. At the time, I played with people of that nature and we were all jamming, most of the time between the regular acts booked in for the night, when we weren't headlining somewhere. In the Sixties it was that kind of feeling where people were coming together, trying new things. The Village was the East Coast "Haight Ashbury." People were sitting in and experimenting with all kinds of things. It was the days of smoking grass and taking LSD and it filled the streets. People were walking down the streets high, searching. In those days, the people were taking drugs to find themselves and they were taking different kinds of drugs (from those people are taking today). One day in 1969, a really great folk singer came in and just started singing and jamming with us on stage. He happened to be Tim Hardin. He liked my playing. So, after the jam, Tim and I were walking down through the energy of Bleecker Street, and we both agreed that we would like to get together sometime. So he gave me his phone number. Later, because (cellist) Richard (Bach) and I were no longer working, I gave Hardin a call. "Well, you know," Tim said, "I'm putting a new group together and we're gonna be doing some concerts. There's going to be a small one at Woodstock. It's going to be one of the lesser, smaller concerts and then we're going to go on to some really BIG ones, like the World State Pavilion." Woodstock was going to be our public rehearsal. Tim said, "Come on up and jam and rehearse with us. We're gonna do these gigs. Let's get together." I told him about Richard, too, and he said, "Sure, tell him to come on up." Tim Hardin was a fantastic songwriter and lyricist. Really great. He had a lot of sensitivity to his music, almost a jazz sensitivity. He wrote "If I Were a Carpenter." Q: You know, I've always wondered about this: With the major lineup that was scheduled at Woodstock, how could anyone believe that it would be small? It seemed like… well, remember, at that time a lot of great musicians were jamming together, but the other side of that jamming was a need to experience peace, anti-war and to experience other levels of consciousness through music and creativity. MURUGA: Rock'n'roll, folk music and Eastern music were coming together in a mesh of creative people. Great musicians like Dylan, Hardin, Paul Butterfield, Al Grossman—who was Dylan's manager—and a lot more were all living and working out of Woodstock at the time. So my impression of it was that they thought it was going to be a lot of really great, artistic musicians coming together in a jam. It wasn't going to be the biggest concert because there were other concerts planned that were being more highly promoted. Who would've expected that anybody would travel all that way to go to some little town in the middle of New York (State) to see a little concert? No one expected half a million people. You throw a concert and you could say, "Well, I'm going to get some great musicians to play and we expect 50,000 or less." You wouldn't expect half a million people. So, my wife, Richard and I went up to Woodstock and we arrived at night. We knocked. There was Tim totally stoned on something that was even further out than LSD, sitting in his living room nude. He had a great big watermelon sitting in front of him and he was just eating it and playing music with a big jebox. He sat there just like a very illuminated soul, singing and playing his guitar. He had no embarrassment about being naked. He invited us to come on in and then he put on some shorts and offered us some watermelon. (laughs) That was my first get-together with Tim Hardin, other than jamming at the café in New York. He said that we were going to have some rehearsals the next day. He'd invited different musicians: Ralph Towner and Glen Moore, the bass player. He (Ralph) was one of the guitar players; the tabla player has since passed away. But here we are rehearsing with a whole slew of people, and as we played Hardin would leave and not come back for several hours. We were rehearsing and, you know, we needed to know which way the tune should go, but (he wasn't there). He'd come back hours later and say, "I'm sorry for being gone and here's some clothes for you and you and you." He would give somebody a pair of pants and another a shirt and somebody else a leather vest. He was very generous and open-hearted, very loose, but we were feeling, "Geez, we're gonna play these concerts and we need to know the material and here he is coming IN and out of the rehearsals, when we need to learn the songs." He was just very loose about it. He'd say, "Oh, here's the songs and here's how they go," and then he'd just split again. That's how rehearsals went. So the concert date came and we're on our way to Woodstock, but the actual place was some miles away in a large meadow with hills surrounding it, sort of like a valley kind of area. Well, when we got out there in the car, we didn't get very far because there was ten miles of cars…. Q: What time of day was this? MURUGA: Early in the morning, and we were still driving right up into the afternoon. It got to the point where we were supposed to be there but we could not get to the concert area because there were so many people. So what happened was, they hired helicopters to come and get us. We couldn't drive to the backstage area. Q: Who hired the helicopters? The promoters?

MURUGA: Yes. They had two or three helicopters; I believe that they were there in case someone got sick or there was an accident. As it turned out, the helicopters were also there to get the musicians in and out, but I didn't know that at the time. Keep in mind that Woodstock became a city that day. Almost a million people came in that one day. It was a city overnight. The car finally took us to the Holiday Inn, I believe—or maybe it was a Howard Johnson's—I don't remember. That was the most fantastic motel scene that I've ever seen. There was Ravi Shankar, Sly Stone, Janis Joplin and everybody who was there to play the concert. I saw Alla Rahka, who was one of my heroes, having a cup of coffee. And that blew my mind because at that time I didn't know that spiritual Indian—Hindu—musicians would even drink coffee. I was sort of naïve to that. There was my tabla hero drinking coffee. There was Janis Joplin holding a fifth of whisky above her head just yelling to the people who were leaving for the stage area: "If you find any groovy looking guys, bring one back for me!" (laughs) She was really stoned on her whisky, walking around, laughing, and you know it was just this vibration of joy coming together. There was this feeling of partying and really getting down. It had the feeling of partying for peace. I have this (he reaches for a button). What does that say? Q: "Woodstock—Peace and Music." MURUGA: Yeah, that was the motto. And that's why I say that people were stoned in those days but they were looking for themselves, they were looking for peace. We had the feeling that all of the straight people who were the ones starting wars and all of the children were saying, "Why should we listen to you and be like you?" So, they were looking for mind-expanding elements. And yet a lot of people went beyond using those things. In some cases, like in Hardin's, it killed. Anyway, the motel was still a little ways from the stage and we needed helicopters to take us over. There were so many people that you could no longer drive in. You couldn't go through them. Matter of fact, there were so many people that the producers said, "Well, this is just too big, too gigantic. It's a happening. We can't charge the people. You can't even get to one person. There's a million people here confronting us." Q: Was that still in the morning of the first day? MURUGA: Yeah, that was in the first day. The fences went down and the people just went through. Q: When was the festival supposed to begin? MURUGA: Well, it was a 3-day festival, but I don't remember the opening time. Richie Havens and his band opened, playing the first hour or two—longer than he was supposed to. He was supposed to go on for half an hour or so but he just kept on playing. But that's getting ahead of the story. So, here we are at the motel waiting for the helicopter and I see this man in a long beard and flowing robe. He was the most spiritual being that I've ever seen. I was pretty stoned, but I was also into meditation. I was searching for myself. Here I saw this man, not knowing that he was the Swami Satchidananda. Later it all came together and I learned that he had been asked to open the festival and speak to the people. He was a spiritual figure at the time, Peter Max's guru—who had made him well known in the Sixties through books that had Swami Satchidananda's writings and Peter's little sketches. The Swami was known throughout the Sixties as the guru for many of the hippies. There in the hotel I had both my clay and my squeeze drums and I sat down in front of him. I didn't say anything, but thought that if this guy's really of such high consciousness, he's going to know, he's going to recognize that I'm really seeking. So I started. Here I am, sitting before Swami Satchidananda, playing my drums. But the helicopter came and took him away. So I said to myself, "I guess he didn't get anything out of that." Later, the helicopter came to get us. It picked us up and here we are in the helicopter and WOW! I could see this whole field of people—Hardin, friends, and me. A half million people lay in my eyes, as far as I could see. That's what it was like, as far as I could see. It looked like Africa when the ants cover ten miles of hills. We got off the helicopter backstage where they had tents set up, and I saw the Swami there. Remember, I still didn't really know who he was. My heart started drumming. I said, "I've got to get to know this guy more." Then he said, "There's that American boy who plays the drums much like the tabla drummers of India." Well, I heard him say that and there was my connection, so I went right up to him and I said, "Sir, you don't have to explain what I play like. I'll play for your friends here." They happened to be some of his disciples. I started playing, closed my eyes and went deep within. And all of a sudden a voice inside said, "Why are you taking up so much of his time? Just give him an example. You want to ask him some important questions. Don't be so full of you playing. Ask him. He's got the knowledge." So I stopped playing and I said, "Sir, what is life about?" He pointed at all those people. It felt like each person was an atom, a molecule, and it was humming, it was buzzing, it was thick with them. They were alive to the max, and that was Woodstock, as far as you could see. It was indescribable. The Swami said, "See those people?" I said, "Yes." He said, "They're energy." Now I I began to see people as energy. And he said, "You know, you're energy and all of you musicians who have come together here at Woodstock are, too. Now, this energy of the audience has come to see the energy of all the different bands. You are amongst them. When you go out there on stage if you are positive, you can help direct the energy of the audience to go positive. If you're negative, you could help them to go negative. The choice is yours, and that's what life is. Life is energy with a choice of going positive or negative." That was his answer. It took Woodstock for me to get that message, which some may not think is very important, but to me it was the most important answer in my life. Just then I saw Tim Hardin start to walk toward the stage, and I got up to go see him and I saw also that a photographer was going to take some pictures. I thanked the Swami and he said, "Say, what's your name?" I said, "Steve Booker." He said, "Ah, Book Booker," and he started laughing and joking. "Booker, you come and see me in New York. Come to my office. I'm at the Integral Yoga Institute, 500 West End Avenue. Come and see me." Well, you know, I'd been seeing pictures of him plastered on the walls of New York for a few years but I didn't know that that was him. Suddenly, I realized that it was. Then a disciple of his said, "He never asks anybody to come see him. It must be for some special reason." Well, later I went and became a disciple, and he gave me the name "Muruga." If it hadn't been for Woodstock, I wouldn't have had my initiation in Yoga guidance, which later further transformed everything else. It gave me a new kind of music, It gave me and the world the Nada Drum. Q: You mentioned that as this was all happening you were going after Tim Hardin, who was heading toward the stage.

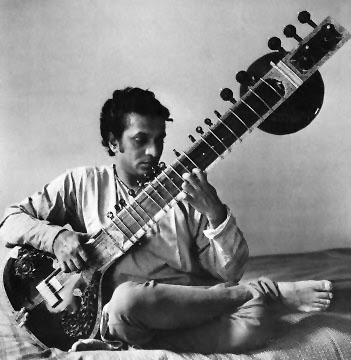

Richie Havens kept the crowd going for an hour or two, and then somewhere in all of that they brought us up. When we walked on stage it was an awesome experience. It was just starting to get dark and there were a half million people there, all spread out before us. Instead of applauding they cheered and each lit a match, a lighter or some sort of flame. It was like looking into an ocean of stars. Whether or not I played, whether or not anything else happened, just to see that was a sight to behold. That was a divine, divine experience. I can't put it into words. After a while we played and, I must say, not well. To everyone's disappointment, Tim Hardin was more stoned that we would have wanted. Since he was the director and the one we needed to follow, it was rather difficult because he barely wobbled up on stage. When we ended it started drizzling and then it began to rain. I remember Ravi Shankar coming on and they had to put a tarp over his head and he had to tune his instruments (again) because the humidity and the rain were making the subtle tablas and sitar go out of tune. But here on stage is one of my heroes, and I'm sitting on the stage, ten or fifteen feet back, listening to him playing—which was just a great, great honor. After that I went backstage. It was raining and I was wet. It had got to the point where the helicopter was needed for really important emergencies, like if someone had a baby or someone got sick on drugs and it wasn't readily available for the musicians, except that Tim Hardin got on the helicopter and went back to the motel, but I missed it. I had to spend the night there, and we were supposed to do a gig the next day at the World State Pavilion. Since it was raining, I tried to dry off near a bonfire. There were people walking around with clothes on, with clothes off, just totally being much like in a nudist colony and people being very free. The scene had a very spiritual feeling to it. But here I am at the bonfire and believe it or not my pants caught on fire. I admit that I got a little bit mad while trying to put it out. Here I am at Woodstock, I missed the helicopter (because Hardin didn't let me know it was going), my $1,600 mahogany Gretch drums are wet and they may be warping ' cause I didn't have a tent, and I'm stuck overnight in the middle of the wet, muddy field. Finally, somebody offered me (a tent) and I put my drums in there. Then it was difficult 'cause I couldn't roam around too much. I felt like I needed to watch the drums, so a little paranoia was there with me and I'm just bummed out. But then I gave in to the whole thing and said, "Wow! Here I am with all of these people and this is really a far-out place to be." The next think I know I hear "the Star Spangled Banner" and it's Jimi Hendrix playing (backstage)…. I slept in the tent overnight and got up in the morning trying to figure out how I was going to get back to the motel where I had left my wife. I'm sitting there, can't get the helicopter 'cause they're busy and Tim Hardin's not there to use any influence he might have. I got mad at Hardin. Q: So here it is the second day at Woodstock and you're stranded. How did you get back? MURUGA: I saw Arlo Guthrie sitting in the tent and he said, "Well, I'm just waiting for my ride to come pick me up and we're gonna get back to the motel." So, I got a lift with Guthrie out of Woodstock, which was very enjoyable. I found my wife at the motel and went back to Tim Hardin's house. From there, we got chauffeured to New York where we did the World State Pavilion opposite Odetta and the Incredible String Band. Just keep in mind that with all of the people who were there (at Woodstock), some could have put down the fact that we were on drugs, but try to get a half million people together and have no real casualties. A few women were pregnant at the time and had their babies (six were born during Woodstock), and that's no casualty. That's being born into the new world, the Woodstock Nation. A few people got hurt from some accidents. Maybe some took too many drugs, a couple of people died, but in comparison it had far fewer problems than any modern town would experience in three days. All of those people were there with a peaceful attitude just sitting, watching the concert, having fun, enjoying others, making love and being loving. So that's the beauty of it. And it was one of the biggest, most major entertainment events in American history, at least as far as getting that many people together in one place, for peace. So don't underestimate a little concert, because it could be the biggest one in your life. It might become history. |

MURUGA: I saw Tim and a photographer there. I decided, "Well, if they're going to be taking pictures, I might as well be in them." It was a good move, because just about in the centerfold in the "Woodstock Remembered" book there's a picture of Tim Hardin, Richie Havens and myself. I only stepped into that picture just a second before it was snapped. Tim and Richie were friends. I knew Richie from Detroit, jamming with him at his apartment and at the Café a Go Go in New York. Then Richie went to play and we were all intense. It was fantastic, because…picture yourself with the energy of all those people, even though they're on the other side of the fence. There was a little separation and we had more space in back for the musicians than the people out front had, but their energy came through it all. (In the area backstage) you could walk through and look into one tent and Ravi Shankar and Alla Rahka were there tuning up their instruments. Look in another tent and there's Sly Stone. Look in another, and there's Jimi Hendrix. All of the musicians who were there were hanging out in these tents and for a young musician like myself, it was like a dream come true. What a beautiful trip. Before Richie went on stage, the first one on was Swami Satchidananda. The people in charge felt that if he were to set the tone and say something positive, that it would help the people to keep control and give the festival a positive momentum. I would just like to read the exact words that he spoke:

MURUGA: I saw Tim and a photographer there. I decided, "Well, if they're going to be taking pictures, I might as well be in them." It was a good move, because just about in the centerfold in the "Woodstock Remembered" book there's a picture of Tim Hardin, Richie Havens and myself. I only stepped into that picture just a second before it was snapped. Tim and Richie were friends. I knew Richie from Detroit, jamming with him at his apartment and at the Café a Go Go in New York. Then Richie went to play and we were all intense. It was fantastic, because…picture yourself with the energy of all those people, even though they're on the other side of the fence. There was a little separation and we had more space in back for the musicians than the people out front had, but their energy came through it all. (In the area backstage) you could walk through and look into one tent and Ravi Shankar and Alla Rahka were there tuning up their instruments. Look in another tent and there's Sly Stone. Look in another, and there's Jimi Hendrix. All of the musicians who were there were hanging out in these tents and for a young musician like myself, it was like a dream come true. What a beautiful trip. Before Richie went on stage, the first one on was Swami Satchidananda. The people in charge felt that if he were to set the tone and say something positive, that it would help the people to keep control and give the festival a positive momentum. I would just like to read the exact words that he spoke: