| Search JoyZine with Google Site Search! |

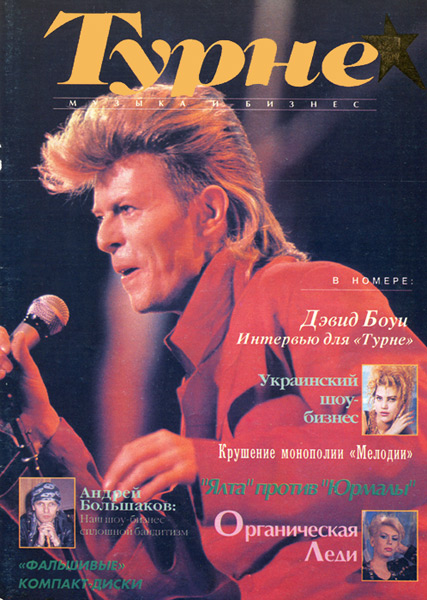

David Bowie

Interview by Joy Williams

David Bowie has made his career a series of charged, contradictory images—androgynous, alien, decadent, star, fashion plate, traveler—while making increasingly avant-garde music. He has drawn on freely-acknowledged sources, from Marc Bolan to the Velvet Underground to Brian Eno, put his own mark on them, then abruptly moved on, leaving behind imitators of each of his phases. As Bowie himself once said: "It's not who's first that's important, but who is second." Born David Robert Jones on January 8, 1947, in London, he took up the saxophone at age 12, and when he left Bromley Technical High School to work as a commercial artist at an advertising agency three years later, he began playing in part-time in bands. A punch from high school chum George Underwood permanently paralyzed Jones's left pupil but didn't end their friendship; Underwood later designed two Bowie LP covers. Three of Jones' early bands, the King Bees, the Manish Boys (produced by Shel Talmy and featuring session guitarist Jimmy Page) and David Jones and the Lower Third, each recorded a single. In 1966, having changed his name to Bowie (after the knife) to avoid confusion with Monkees' Davy Jones, he recorded three singles for Pye Records, then signed in 1967 with London/Dream. Several London singles, notably "Love You Till Tuesday" and "The Laughing Gnome," hit the U.K. charts, and London issued The World Of David Bowie (most of the songs on that album, and others from that time, were collected on Images). But Bowie hadn't yet settled on pop music. He spent some weeks in a Buddhist monastery in Scotland, but decided not to take the monastic vows. He then apprenticed himself in Lindsay Kemp's mime troupe, exchanging musical scores for pantomime lessons, in 1967. He also acted in a 15-minute short ("The Image"), a feature (a bit part in "The Virgin Soldiers"), a commercial for ice cream bars and a BBC-TV play, "The Pistol Shot." With his co-star from the play, he started Feathers, a mime troupe, in 1968. American-born Angela Barnett met Bowie in London's Speakeasy and married him on March 20, 1970. (Son Zowie Bowie was born in June 1971.) After Feathers broke up, Bowie started the Beckencham Arts Lab in 1969 to experiment with theater and music. To finance the project, he signed with Mercury Records. Man Of Words, Man Of Music included "Space Oddity," an international hit at the time of the US moon landing. Marc Bolan, an old friend, was beginning his rise as a glitter-rocker in T. Rex, and introduced Bowie to his producer Tony Visconti; Bowie mimed at some T. Rex concerts, and Bolan played guitar on Bowie's "Karma Man" and "The Prettiest Star." Bowie, Visconti, guitarist Mick Ronson and drummer John Cambridge toured briefly as Hype. Ronson eventually recruited drummer Michael Woodmansey from his old blues band, the Rats, and with bassist Visconti they recorded The Man Who Sold The World, which included "All the Madmen", inspired by Bowie's institutionalized brother, Terry.

Hunky Dory was Bowie's tribute to the New York City of Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground and Bob Dylan, with Bowie's virtual theme song, "Changes." By 1971, Bowie was working hard on his image. He told Melody Maker he was gay in January 1972, and enjoyed the idea of a cult growing around his androgynous image. New manager Tony DeFries gave Bowie accoutrements of stardom—limos, champagne, first-class hotels - and Bowie began to think about the star as character. Enter Ziggy Stardust, the doomed messianic rock icon. The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars made Bowie the star he was portraying (the Spiders were the band: Ronson, Woodmansey and bassist Trevor Bolder). The live show, with Bowie in futuristic costumes, makeup and orange hair, was a sensation in London and New York, and "Starman" became a hit, while Ziggy Stardust sold a million copies. Bolan and other British glitter-rock performers barely made the Atlantic crossing, but Bowie emerged a star. Aladdin Sane was a surrealistic diary of his first American tour, with hits in "The Jean Genie" (the title is a pun on playwright Jean Genet's name; the song is about singer Iggy Pop) and Bowie produced albums for his inspiration, Lou Reed (Transformer, including "Walk On The Wild Side") and Iggy Pop (Raw Power) and wrote a glitter anthem for Mott the Hoople, "All The Young Dudes." In 1973 Bowie announced at a London concert that ended a sixty-date British tour, that he would never again perform on stage. He disbanded the Spiders and sailed to Paris to record Pin-Ups, a collection of covers of mid-Sixties British rock. The retirement didn't last; Bowie videotaped an invitational concert for American TV, The 1980 Floor Show, with guests the Troggs and Marianne Faithfull. Meanwhile, he worked on a musical adaptation of George Orwell's 1984, but was denied rights to the book by Orwell's widow. He rewrote the material for Diamond Dogs, and mounted a $250,000 extravaganza to tour America. Midway through the tour, however, he scrapped the sets and costumes and appeared thereafter in baggy Oxford trousers, without makeup, his hair trim and its natural blond. His sound, too, underwent revision: he toned-down the glitter-rock, hired a new band led by guitarist Earl Slick (former musical director for the Main Ingredient and an ex-James Brown sideman) and added soul music standards to his repertoire. The new Bowie was an entertainer, the Thin White Duke (as he called himself in a song and an unpublished autobiography).

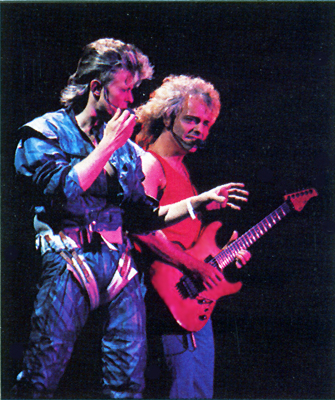

Bowie ended the 1974 tour by recording a live double set in Philadelphia (the then-current capital of black pop), then booked Philly's Sigma Sound Studios to cut Young Americans with guitarists Slick and Carlos Alomar, bassist Willy Weeks and Emir Ksasan and drummer Dennis Davis. Two singles from that album became favorites in discos, and "Fame" (co-written by Bowie, Alomar and John Lennon) became Bowie's first American #1. Bowie moved to Los Angeles and became a fixture of American pop culture. He also played the title role in Nicolas Roeg's movie, The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976). After recording another album of what he called "plastic soul" with the Young Americans band, Bowie left Los Angeles, complaining that he had become predictable again. He returned to England for the first time in three years then settled in Berlin, where he lived almost as a recluse, painting, studying art and recording with Brian Eno His work with ENO—Low, Heroes, Lodger—took him into electronic music, and the occasional narrative song employed novelist William Burroughs' random "cut-up" writing technique. Bowie revitalized Iggy Pop's career by producing The Idiot and Lust For Life, and toured Europe and America unannounced in 1977 as Iggy's pianist. While in America, he narrated Eugène Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra's recording of Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf. He spent most of the next year in Berlin acting with Marlene Dietrich and Kim Novak in Just a Gigolo. He then embarked on a world tour with a band that included Davis and Murray and, variously, violinist Simon House of Hawkwind, synthesizist Roger Powell of Utopia, and guitarist Adrian Belew, who had worked with Frank Zappa. A second live album, Stage, was recorded during the U.S. leg of that tour. Work on Lodger, his third collaboration with ENO, was begun in New York, continued in Zurich and completed in Berlin. In 1979, Bowie returned to New York to record the paranoiac Scary Monsters, updating "Space Oddity" in "Ashes to Ashes (The Continuing Story of Major Tom);" a 12-inch single distributed to radio stations only, segued "Space Oddity" into "Ashes to Ashes." Bowie also made some of the most innovative promotional rock videos with songs from Lodger and Scary Monsters. He spent 1980 in the title role of Bernard Pomerance's Broadway play The Elephant Man in Denver and Chicago and on Broadway. And while rockers awaited the latest new Bowie, he kept himself in royalties by collaborating with Queen on 1981's Under Pressure and providing lyrics and vocals on Giorgio Moroder's title tune for the sound track of Paul Schrader's 1982 film Cat People. His music provided the sound track for Christiane F., the film biography of a young heroin addict. In 1982, Bowie appeared in a BBC-TV production of Bertolt Brecht's Baal. He portrays a 150-year-old man in the movie The Hunger. In 1983 he returned to recording with Let's Dance, produced by Nile Rodgers of Chic, a calculated effort to get in step with the sound of today, rather than tomorrow or yesterday, Bowie's far more common habitats. Not surprisingly, as it usually happens, Bowie succeeded at what he had set his mind to, and the record was a worldwide smash. "Let's Dance," "Modern Love" and "China Girl" may not be the Thin White De's finest creations, but they do hit a solid compromise between art and commerce, and didn't harm his reputation nearly as much as expand his audience. In 1989 Bowie's new band, Tin Machine, released its self-titled 1989 debut. The band's music was termed "aggressive, direct and brutal," a sound reflecting the explosive synergy generated by its four members: David Bowie (lead vocals, guitar), Reeves Gabrels (lead guitar), Hunt Sales (drums, vocals) and Tony Sales (bass, vocals). Written and recorded in just six weeks, Tin Machine documented these four talented, very different, yet complementary, individuals. On Tin Machine the quartet's evolution as a musical unit is in full evidence. While the album suggests the immediacy of Tin Machine's debut effort, it's coupled with the ease of experience which the band has gained in the studio and on tour during the last two+ years. Anchored by the Sales brothers' steady, R&B-flavored rhythms, punctuated by Gabrels' growling guitar and Bowie's expressive vocals, Tin Machine has harnessed its early blistering noise experiments and streamlined sound, adding more subtle textures and melodies, taking risks without compromising any of the first album's breathtakingly raw energy. "I think we were so desperately fearful of exactly what it was we were trying to write or produce, that there was maybe an exaggerated urgency to what we were doing," David recalls about the group's first recording. "I find that very satisfying, by virtue of the fact it is a group's first effort. And I like the abrasion factor." "The first album was groove-oriented, "adds Tony. "It was right to the throat. Reeves called it 'pinstripes and purple haze.'"

One factor which influenced the band's approach to its new recording was Tin Machine's brief world-wide tour. "On this album we had done twenty live dates and we'd known each other for a couple of years," Reeves says. "We kind of knew what we sounded like having played more together. "On the first record it was a matter of 'How do you do?' 'Okay,' 'What do you think of this chord?'" Hunt adds. "But now we've had some time to love each other and hate each other. I think it shows on this record." Another important element was recording the album in Australia. "We wanted to put ourselves into a light that we did not feel entirely comfortable in," Tony explains. "The unfamiliarity would make us work better together, since there was nothing else for us to latch onto." The basic tracks for the album were written and recorded in just over three weeks in Sydney with Tim Palmer once again co-producing. While the first album was all manic sparks, Tin Machine II reflects the band's impressions of Australia's expansive landscape. "It may sound like a cliché, but a lot of tracks have an openness to them," Reeves points out. "'You Belong In Rock & Roll' and even 'Shopping For Girls' to a certain degree, have a bigger horizon to them sonically, and I think Australia had something to do with that. It's a place that moves slower and it's so wide open, almost like Texas." Reeves and David continued to refine the album during the Sound & Vision tour, picking up whenever David had a break. "David would call up and say, 'I'm going to have a week off in Miami in a month, if you want to meet me there, we can do more stuff,'" Reeves explains. "For example, 'Goodbye Mr Ed' was just a rhythm track until we got to Miami." The album was finally completed in England in the spring. "Lyrically, especially, David really responds to what's going on around him while we're doing it," Reeves adds. "Making this album was more of a journey inside, thinking about relationships, the romantic side, instead of trying to point out the problems in the world. Although Tin Machine was formed only three years ago, the band's origins can be traced to the recording sessions for Iggy Pop's landmark 1977 album Lust For Life. It marked the first time Bowie, who co-produced that album as well as contributing keyboards and vocals, and the incomparable Sales brothers, Hunt and Tony, had played together. "We talked back then about the possibility of doing something else together later," Hunt recalls. But it wasn't until Bowie met Reeves Gabrels in 1987 that the band that would eventually become Tin Machine really came to fruition. Gabrels had been experimenting with different guitar sounds for over a decade as a session musician and with groups like Boston's Rubber Rodeo. Fascinated by innovators like Adrian Belew and avant-garde composer Glenn Branca, Gabrels started to develop his own vocabulary for the guitar, drawing on a multitude of styles from blues and R&B to country, rock and jazz. The brothers Sales enjoy a remarkable chemistry. "It's hard, crazed energy," David says about them. "They're not used to sessions. They're not really used to recording studios. They're very much a live couple, so there's a different approach to the studio than if you ended up with session guys or young guys who don't know, who haven't the wealth of experience playing in every conceivable format from Todd Rundgren through.... Hunt was working with a soul band when he was 13!" He was 15 when he and his slightly older brother Tony held down the rhythm section duties on Todd Rundgren's first solo album. Tony played with Iggy Pop's Stooges, with Bowie at one point, with many others, until he hit a tree at 75 mph one night. "They found me basically dead, not breathing, with the gearshift through my chest," Tony revealed. He was in a coma for eight months. "And of all the people I'd known and played with, David was the only one who came to the hospital during all that time." "I met David about a year before he even knew I played guitar," Reeves recalls. Gabrels' wife, Sara, had worked with Bowie on his Glass Spider tour, eventually offering David a tape of her husband's work. Several months after the tour ended, Bowie called Gabrels and said, "You're the guitar player I've been looking for!" "Tony, Hunt and I had been talking about a similar kind of music we'd heard in our heads and wanted to play," David asserts. "When I met Reeves he was saying the same things. Tin Machine kind of evolved as we realized we all wanted to play the same kind of music." Bowie and Gabrels first took their collaboration public, performing together at the 1988 Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) benefit concert in London. "That was the first time the sound really happened," Reeves admits, "but what was missing was Hunt and Tony." Several months earlier, celebrating the close of his Glass Spider tour, Bowie had encountered Tony at a party in Los Angeles. "I hadn't seen David since the US Festival in 1983," Tony recalls. "But when we met that night he raved about this guitar player he'd found, and pretty soon the four of us were starting this thing up." The band members received their first formal introduction to each other just prior to recording the first Tin Machine record in Montreaux, Switzerland. "I had just met Hunt and Tony the day before we went into the studio," Reeves recalls. "I was still having trouble remembering which was Hunt and which was Tony and they were probably having trouble remembering what my name was, but there we all were, playing together!" More than anything else they have in common, the quartet shares an adventurous spirit despite the group's apparently simple musical line-up of guitar, bass, drums and vocals. "We wanted to have that connection, that intimacy," Tony says. "With something as simple as this you've got to focus. You’re drawn in by everybody. When you've only got four or five guys on stage, everybody is pushing and pulling so quickly that it's really exciting. It's more stimulating than being in a twelve-piece band." "It's a commitment to real writing and real expression of form," David adds. "It's still a simple structure, but I think we've moved quite a long way forward on it." And beyond that, "It's a fun band to work in. Reeves and I are the serious ones, I guess. Around Hunt and Tony, we supply the straight lines." Watching Tin Machine play, as I did at the Hollywood Palladium, is persuasive evidence that it is possible for a star of the calibre and charisma of David Bowie to submerge himself in the machinations of a traditional rock’n’roll band—previous depositions from Paul McCartney & Wings, Todd Rundgren's Utopia and others to the contrary. The return of the Thin White De in the non-theatrical guise of T-shirted lead singer for just another loud quartet strikes some as yet one more chameleon pose in a decades-long string of them. And not without good reason. When fellows of a certain age who've delved into every rock genre decide to simply let it rip, there's an element of calculation seemingly present. Then again, so what? Tin Machine, which has no pretensions toward an especially youthful image, also presents a convincing case that reckless abandon in playing isn't synonymous with youthful zeal. There's a knowing maturity here—a dignity and a seasoned-ness—that doesn't spoil, but rather manages to somehow complement the roughhouse nature of the thing. Live, Tin Machine is anything but a star turn for Bowie, and not because Bowie was unduly humbling himself in the service of band democracy. Rather, the quartet sounded like an honest unit committed to kicking each other's musical rears while staying in tight step. And this seems very strange, that a star of David Bowie's magnitude—one of the most influential rock musicians of all time, a legendary icon—would insist on being "just one of the boys" in a democratic band. Because he was extremely sick with the flu and had to sing that night, my interview became restricted to a requested "less than 10 minutes," so I decided to cut the small talk and go right to the big question:

Q: So, what’s with this, "I'm just a member of the band," routine? DAVID: It's just one big family. I think we have really succeeded in being a BAND. How it's received by others is literally their problem. Q: No, no... good frontmen—and you're certainly one of the all-time best—can control the audience. DAVID: It's their choice if they're going to do that or not. It's my choice not to. Q: It hasn't always been like that, though, has it? It seems like you've perhaps let go and submerged yourself in the band. DAVID: It's not a question of submerging myself, it's that my responsibilities are different. When I do solo performances I endeavor to create some kind of concept, some kind of show that's entertaining within the values as a solo artist. But with this particular band, it doesn't call for theatrics. It's very much about the music we play rather than the visuals in the music, which a lot of my solo work has been. Q: Is that a relief for you, then? DAVID: No. It's just a different form. If you've done something once, why do it again? Q: You're focusing differently. DAVID: Yes, at the moment. And at the moment I'm enjoying what I'm doing with Tin Machine an awful lot. On the other hand, I'm also working on some solo things parallel with it. Q: So, Tin Machine is a project that satisfies certain… DAVID: Certain needs in music. Q: You wrote or co-wrote everything on the album. Someone said to me, "Why is Bowie sounding like this?" But if you wrote it, it means you chose to sound like this. DAVID: It mainly had it's roots in the very late seventies. All The Young Heroes, Scary Monsters and, to a certain extent, the melodic structures. Reeves Gabrels, by the nature of his playing, has a fair bit of both Fripp and Adrian Belew. Q: What I think is unusual about you is that a lot of people are either glammy—showy, visually-oriented—or seriously musical, but you like to do both. DAVID: Hunt [Sales, the drummer] has got enough charisma, or attitude, whichever way you want to look at it.... There is no small amount of personality in the band. There are radical guys in this band. Everybody is terribly focused on trying to make something of their lives. And I don't mean in the career fashion, but trying to find out what their lives are about. I think that's also something that drives this band very much. Q: I think that happens to a lot of people at some point, especially artists. You spend all this time just thinking. And some of it is about yourself. DAVID: I think as you get older, you apply more and more to yourself rather than looking for immediate gratification or quick responses to daily situations. Q: What is it about music for you? You've got more like an actor personality than most rock musicians, who typically spend their lives, at least professionally, with one image. DAVID: Oh, God. I think it doesn't help having the ability to write in so many styles. Q: Why? Because the critics get upset? DAVID: No, no, no! It has nothing to do with them. For me, myself. I mean, I like so many kinds and styles of music myself, as a listener, and I unfortunately have the facility to write more or less any style that I tend to like. So, it's not like I'm forced into one style of music because that's the (only) kind of music I write. Q: I can just hear people out there saying, "Oh, I should have this problem." DAVID: No, it's not a good problem to have. Believe me, it really isn't. Because you find you have to be careful. If you start doing that too much, you kind of end up floundering. So, I keep pulling back in again every few years, and I come back to a smaller sound and then start expanding again. I find it no trouble at all to go from some slushy ballad to kind of a heavy, heavy rock piece, or kind of a dance thing. It's all just music to me, and I love writing it and I love playing it. Q: When did this start? You're one of these people about whom somebody else will say, "One day when I was 12 years old I saw David Bowie on TV. That was it. I knew. This was what I had to do for the rest of my life..." DAVID: Actually, for me it was Little Richard. Q: Well, you certainly had your flamboyance there! DAVID: Oh, he was everything. I mean, I just wanted to be the sax player in his band. Q: And you never became a minister. DAVID: No! No, I stayed away from that one! I'm spiritual, but not that spiritual! Q: What are your memories of Russia? DAVID: My biggest disappointment was having to step over drunken people lying on the pavements at night in Moscow. Q: Or even in the streets. DAVID: Yeah, they're just about anywhere after a certain time in the evening. I haven't been to Russia since 19… Let's see, when was the last time I went? Probably 1981? Something like that. I only went in the cold, heavy years. I know nothing of Russia under the Gorbachevs and the Yeltsins. I bet it's a total change. When I was there, it was Brezhnev and Andropov and those guys. It was very, very heavy. I couldn't go anywhere without this guy following me. I had to have this guy on my back and it was really hard. I guess the outlands haven't changed much. I went right through on the Trans-Siberian Express into Moscow, which was just sensational. On the positive side, I found everybody I talked to eager to exchange information on art and music. It was just wonderful. When you can get through the language barrier, it gets quite easy to converse and compare things. I had books with me where I would point to illustrations and paintings Q: Well, you should go back now. DAVID: Yeah! I can't wait to go back. It would be nice to see what it's like now. Q: It's going to be a painful birth. But right now, if you like lots of strange, exotic adventures, it's certainly the place to go. DAVID: Oh, absolutely. |